On 2 October 2015, I gave a talk to a group of provincial level provincial journalists in Sri Lanka who had just completed a training course in investigative journalism.

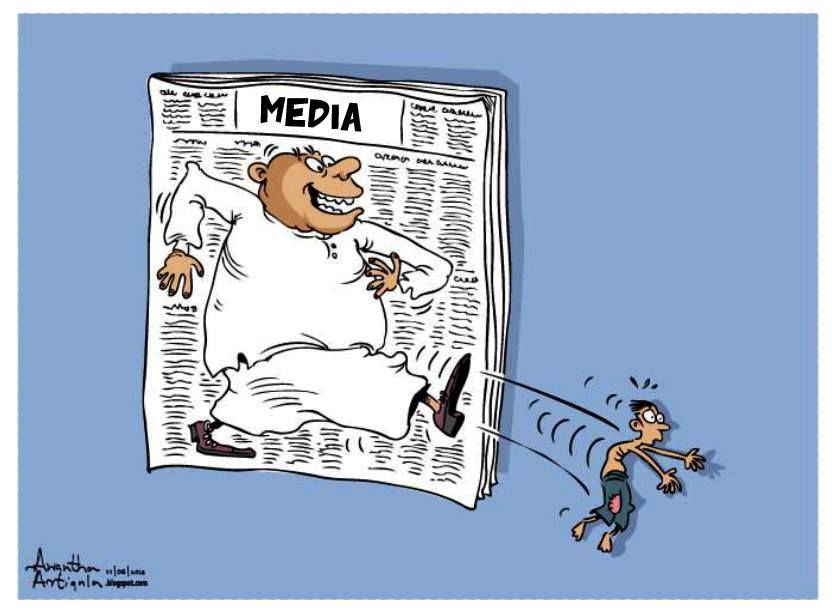

I looked at the larger news media industry in Sri Lanka to which provincial journalists supply ground level news, images and video materials. These are used on a discretionary basis by media companies mostly based in the capital Colombo (and some based in the northern provincial capital of Jaffna). Suppliers have no control over whether or how their material is processed. They work without employment benefits, are poorly paid, and also exposed to various pressures and coercion.

I drew an analogy with the nearly 150-year old Ceylon Tea industry, which in 2014 earned USD 1.67 billion through exports. For much of its history, Ceylon tea producers were supplying high quality tea leaves in bulk form to London based tea distributors and marketers like Lipton. Then, in the 1970s, a former tea taster called Merrill J Fernando established Dilmah brand – the first producer owned tea brand that did product innovation at source, and entered direct retail.

He wanted to “change the exploitation of his country’s crop by big global traders” – Dilmah has today become one of the top 10 tea brands in the world.

The media industry also started during British colonial times, and in fact dates back to 1832. But I questioned why, after 180+ years, our media industry broadly follows the same production model: material sourced is centrally processed and distributed, without much adaptation to new digital media realities.

In this week’s Ravaya column, (appearing in issue of 11 Oct 2015), I have adapted my talk into Sinhala.

ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන් සිය ගණනක් අපේ දිවයිනේ නන් දෙස විසිර සිටිනවා. තම ගමේ, නගරයේ හා අවට ප්රදේශවල සිදුවීම් ගැන තොරතුරු හා රූප/වීඩියෝ දර්ශන පුවත්පත් ආයතන හා විද්යුත් මාධ්ය ආයතනවලට නිරතුරුව ලබා දෙන්නේ මේ අයයි.

මේ නිසා ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන් බිම් මට්ටමින් සක්රීය හා සංවේදී පිරිසක්. ඔවුන් බහුතරයක් කොළඹ පිහිටි මාධ්ය ආයතනවලටත්, සෙසු අය යාපනයේ පිහිටි මාධ්ය ආයතනවලටත් වාර්තා කරනවා.

මේ කේන්ද්ර ද්විත්වයේදී ඔවුන්ගේ දායකත්වය නිසි තක්සේරුවකට හෝ සැලකීමකට හෝ ලක් වන්නේ නැහැ. ඇත්තටම ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන් ඉතා අඩු ගෙවීම්වලට ලොකු අවදානම් ගනිමින් සේවයේ නිරත වනවා යයි කිව හැකියි.

ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන් 75 දෙනකුට ගවේෂණාත්මක වාර්තාකරණය පිළිබඳ පුහුණුවක් අවසානයේ සහතික ප්රදාන උත්සවයක් පසුගිය සතියේ කොළඹදී පැවැත්වුණා. එය සංවිධානය කළේ ට්රාන්ස්පේරන්සි ඉන්ටර්නැෂනල් ශ්රී ලංකා කාර්යාලය හා ශ්රී ලංකා පුවත්පත් ආයතනයයි. එහිදී දේශන පැවැත්වීමට මහාචාර්ය රොහාන් සමරජීවටත්, මටත් ඇරයුම් කර තිබුණා.

ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන් විවිධාකාරයෙන් හඳුන්වා දිය හැකියි. ප්රවෘත්ති මාධ්ය කලාවේ බිම් මට්ටමේ සංවේදකයෝ, ජන හද ගැස්ම හඳුනන්නෝ හා සමාජ ප්රවණතා කල් තබා දකින්නෝ ආදී වශයෙන්. මගේ කතාවේ මා මීට අමතරව ඔවුන් දරු පවුල් ඇත්තෝ හා දිවි අරගලයක නිරත වූවෝ කියා ද හැඳින් වූවා.

2015 සැප්තැම්බර් මුලදී මින්නේරිය සමඟිපුරදී වල් අලි ප්රහාරයකට ලක්ව ඉතා අවාසනාවන්ත ලෙසින් මිය ගිය කේ. එච්. ප්රියන්ත රත්නායක නම් ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදියා මා සිහිපත් කළා. එම අනතුර ගැන සටහනක් ලියූ සමාජ විචාරක හා බ්ලොග් රචක අජිත් පැරකුම් ජයසිංහ කීවේ මෙයයි.

“සාමාන්යයෙන් ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යකරුවෝ විවිධ ආකාරයෙන් මාධ්ය ආයතන ගණනාවකට එක වර සේවය සපයති. සපයනු ලබන ප්රවෘත්තිවලට පමණක් සුළු ගෙවීමක් ලබන ඔවුන්ට පැවැත්මක් තිබෙන්නේ එවිටය. අඩු තරමේ ඔවුන්ගේ නම හෝ ප්රචාරය වන්නේ දේශපාලකයකුගෙන් ගුටි කෑම වැනි අනතුරුදායක කටයුත්තකදී පමණි.

“ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යකරුවන් යනු මාධ්ය ආයතනවල සූරාකෑමට දරුණු ලෙස ගොදුරු වන පිරිසකි. ඔවුන්ට සාමාන්යයෙන් ගත් කල කිසිදු පුහුණුවක් නැත. මාධ්යකරුවන්ට ලබා දෙන විධිමත් ආරක්ෂක පුහුණුවකදී නම් වාර්තාකරණයේදී ආත්මාරක්ෂාව සපයා ගන්නා ආකාරය පුහුණු කරනු ලැබේ. එහෙත් ලංකාවේ බහුතරයක් ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යකරුවන්ට ප්රවෘත්ති පිළිබඳ මූලික අවබෝධය පවා නැත. බොහොමයක් මාධ්යකරුවන් එවන ප්රවෘත්ති නැවත ලියන්නට සිදු වේ.

“මාධ්ය ආයතනවලට ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යකරුවා තවත් එක් උපකරණයක් පමණි. මොන යම් ආකාරයකින් හෝ ප්රාදේශීය ප්රවෘත්ති ලැබෙනවා නම් මාධ්ය ආයතනවලට ඇතිය. රටේම මිනිසුන්ට වන අසාධාරණකම් විවේචනය කරන මාධ්ය ආයතනවල ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යකරුවන් සූරාකෑම නැවැත්වීමට කටයුතු කළ යුතුය.”

Full text: ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යකරුවන්ගේ ජීවිත සූරා කන මාධ්ය ආයතන

මේ විග්රහයට මා එකඟයි. මාධ්යවේදීන්ට “මාධ්ය කම්කරුවන්’’ මට්ටමින් සැලකීම හුදෙක් ප්රාදේශීය වාර්තාකරුවන්ට පමණක් සීමා වී නැතත්, එය වඩාත් බරපතළ වන්නේ ඔවුන් සම්බන්ධයෙනුයි.

හොඳින් ලාභ ලබන මුද්රිත හා විද්යුත් මාධ්ය ආයතන පවා ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන්ට ගෙවන්නේ ඉතා අඩුවෙන්. එය ද ඔවුන් සපයන තොරතුරක් හෝ රූපයක් හෝ භාවිත වූවොත් පමණයි. එයට අමතරව නිවාඩු, රක්ෂණ ආවරණ ආදී කිසිවක් ඔවුන්ට හිමි නැහැ.

මේ අසාධාරණයට ලක් වන ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන්ට සිය මාධ්යකරණයේ නියැලීමට විකල්ප ක්රමවේද හා අවකාශයන් තිබේද? ඒවා විවර කර ගැනීමට කුමක් කළ යුතුද?

මේ ගැන මගේ කතාවේදී මා මෙනෙහි කළා. එහිදී මාධ්ය කර්මාන්තයේ පුවත් සම්පාදන ආකෘතිය සමීපව විමර්ෂනය කළ යුතු බව මගේ අදහසයි.

(1802 දී ආරම්භ කළ ගැසට් පත්රය මාධ්ය අංගයක් ලෙස නොසැළකුවොත්) ශ්රී ලංකාවේ නූතන මාධ්යකරණය ඇරැඹුණේ 1832 ජනවාරියේදී. කලම්බු ජර්නල් (Colombo Journal) නම් සති දෙකකට වරක් පළ වූ ඉංග්රීසි සඟරාව මෙරට මුල්ම වාරික ප්රකාශනයයි. එවකට බි්රතාන්ය යටත් විජිත රජයේ මුද්රණාලයාධිපතිව සිටි ජෝර්ජ් ලී එහි කතුවරයා වූවා. එකල ආණ්ඩුකාරයා වූ රොබට් විල්මට් හෝට්න් ද එයට ලිපි සැපයුවා.

මෙබඳු රාජ්ය සබඳතා තිබුණත් පෞද්ගලික මට්ටමින් පවත්වා ගෙන ගිය කලම්බු ජර්නල් සඟරාව පැවති රජය විවේචනය කිරීම නිසා ටික කලකින් පාලකයන්ගේ උදහසට ලක් වූවා. (රජය හා මාධ්ය අතර මත අරගලය මාධ්ය ඉතිහාසය තරම්ම පැරණියි!) මේ නිසා 1833 දෙසැම්බර් මස සඟරාව නවතා දමනු ලැබුවා.

දෙමළ බසින් මුල්ම වාරික ප්රකාශනය වූ “උදය තාරකායි’’ 1841දී යාපනයෙන්ද, මුල්ම සිංහල පුවත්පත ලෙස සැලකෙන “ලංකාලෝක’’ 1860දී ගාල්ලෙන්ද අරඹනු ලැබුවා. (මෙයින් පෙනෙන්නේ මුල් යුගයේ මාධ්ය ප්රකාශනය කොළඹට පමණක් කේන්ද්ර නොවූ බවයි.)

1832 ආරම්භය ලෙස ගත් විට වසර 180කට වඩා දිග ඉතිහාසයක් අපේ මාධ්ය කර්මාන්තයට තිබෙනවා. එය වඩාත් සංවිධානාත්මක කර්මාන්තයක් බවට පත් වූයේ 20 වන සියවසේදී. 1925දී රේඩියෝ මාධ්යයත්, 1979දී ටෙලිවිෂන් මාධ්යයත්, 1995දී ඉන්ටර්නෙට් සබඳතාවත් මෙරටට හඳුන්වා දෙනු ලැබුවා.

මුද්රිත හා විද්යුත් මාධ්යවලට දශක ගණනක ඉතිහාසයක් ඇතත් එහි පුවත් එකතු කිරීමේ ආකෘතිය තවමත් වෙනස් වී නැහැ. එහි සැපයුම්දාමය ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන්ගේ සිට කොළඹ/යාපනය ප්රධාන කාර්යාලවලට එනවා. එතැනදී තේරීමකට හා ප්රතිනිර්මාණයට ලක් වනවා. ඉන් පසු රටටම බෙදා හරිනවා.

එම ක්රියාවලියේදී ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන්ට තීරක බලයක් නැහැ. කලකට පෙර නම් ඔවුන්ගේ නම පවා පත්තරවල පළ කළේ කලාතුරකින්. පුවත් ප්රමුඛතාව හා කුමන ආකාරයේ පුවත් පළ කරනවා ද යන්න ගැන න්යාය පත්රය මුළුමනින්ම තීරණය කරන්නේ කේන්ද්රීය කාර්යාල විසින්. ගතානුගතිකත්වය හා වැඩවසම් ආකල්ප තවමත් අපේ මාධ්ය කර්මාන්තයේ බහුලයි.

මෙය කෙසේ වෙනස් කළ හැකිද? මාධ්ය කර්මාන්ත ආකෘති කෙසේ නවෝත්පාදනයට ලක් කළ හැකිද? වෙනත් කර්මාන්තවලින් ආදර්ශයක් ගත හැකි දැයි මා ටිකක් විපරම් කළා.

තේ කර්මාන්තය ද බි්රතාන්ය පාලන සමයේ ඇරැඹි මේ වන විට ඉතා සංවිධානාත්මකව ක්රියාත්මක වන දැවැන්ත කර්මාන්තයක්. 2014දී ඇමෙරිකානු ඩොලර් බිලියන 1.67ක් (රුපියල් බිලියන 231) ආදායම් ලද මේ කර්මාන්තය ඍජුව ලක්ෂ හත හමාරකට ජීවිකාව සපයනවා.

චීනයේ සිට මුලින්ම තේ පැළයක් මෙරටට ගෙනාවේ 1824දී වුවත්, වැවිලි කර්මාන්තයක් ලෙස තේ වැවීම පටන් ගත්තේ කෝපි වගාව දිලීර රෝගයකින් විනාශ වූ විටයි. මුල්ම තේ වත්ත 1867දී මහනුවර දිස්ත්රික්කයේ අරඹන ලද ලූල්කඳුර වත්තයි. එය ඇරැඹු ජේම්ස් ටේලර් (James Taylor: 1835-1892) තේ වගාවෙ පුරෝගාමියා ලෙස සැලකෙනවා.

සුළුවෙන් පටන් ගත් තේ වගාව ටිකෙන් ටික උඩරට හා පහතරට වෙනත් ප්රදේශවලට ව්යාප්ත වුණා. මෙරට භාවිතයට මෙන්ම පිටරට යැවීමටත් තේ කොළ නිෂ්පාදනය කරනු ලැබුවා.

සන්ධිස්ථානයකත් වූයේ තොමස් ලිප්ටන් (Thomas Lipton: 1841-1931) නම් බි්රතාන්ය ව්යාපාරිකයා 1890දී මෙරටට පැමිණ ජේම්ස් ටේලර් ඇතුළු තේ වැවිලිකරුවන් මුණ ගැසීමයි. තොග වශයෙන් ලංකා තේ මිලට ගෙන ලන්ඩනයට ගෙන ගොස් එහිදී පැකට් කර ලොව පුරා බෙදාහැරීම හා අලෙවිකරණය ඔහු ආරම්භ කළා. ලිප්ටන් තේ ලොව ප්රමුඛතම වෙළඳ සන්නාමයක් වූ අතර අපේ තේවලින් වැඩිපුරම මුදල් උපයා ගත්තේ එබඳු සමාගම්.

මේ තත්ත්වය නිදහසෙන් පසුද දිගටම පැවතියා. ගෝලීය මට්ටමෙන් තේ බෙදා හැරීමේ හැකියාව හා අත්දැකීම් තිබුණේ යුරෝපීය සමාගම් කිහිපයකට පමණයි.

තේ රස බලන්නකු ලෙස වෘත්තීය ජීවිතය ඇරැඹු මෙරිල් J ප්රනාන්දු නම් ලාංකික තරුණයා ලන්ඩනයේ 1950 ගණන්වල පුහුණුව ලබද්දී මේ විසමතාව ඉතා සමීපව දුටුවා. යළි සිය රට පැමිණ තේ කර්මාන්තයේ සියලූ අංශවල අත්දැකීම් ලත් ඔහු 1988දී ගෝලීය දැවැන්තයන්ට අභියෝග කිරීමට තමාගේම සමාගමක් ඇරැඹුවා. එහි නම ඩිල්මා (Dilmah Tea: www.dilmah.com)

ඩිල්මා සමාගම කළේ මෙරට නිපදවන තේ කොළ මෙහිදීම අගය එකතු කොට, තේ බෑග් එකක් ඇසුරුම් කොට ඔවුන්ගේ වෙළඳනාමයෙන් ගෝලීය වෙළඳපොළට යැවීමයි. මුලදී දැවැන්ත බහුජාතික සමාගම් සමග තරග කිරීමට ඉතා දුෂ්කර වුවත් නවෝත්පාදනය හා නිර්මාණශීලී අලෙවිකරණය හරහා ලෝක වෙළඳපොළ ජය ගන්නට ඩිල්මා සමත්ව සිටිනවා.

අද ලොව රටවල් 100කට ආසන්න ගණනක සුපර්මාර්කට්වල ලිප්ටන් වැනි තේ අතර ඩිල්මා ද අලෙවි කැරෙනවා.

ඩිල්මා යනු මෙරටින් බිහි වූ විශිෂ්ටතම වෙළඳ සන්නාමයන්ගෙන් එකක්. එහි සාර්ථකත්වයට මුල දශක ගණනක් පැවැති තේ කර්මාන්ත ආකෘතිය අභියෝගයට ලක් කිරීමයි.

තේ කර්මාන්තය මෙසේ නවෝත්පාදනයට ලක් වෙමින් විවිධාංගීකරණය වෙද්දී අපේ මාධ්ය කර්මාන්ත ආකෘතිය සියවසක් තිස්සේ එතරම් වෙනස් වී නැහැ. මුද්රණ තාක්ෂණය හා ඩිජිටල් උපාංග අතින් නවීකරණය වුවද ප්රාදේශී්ය පුවත් කේන්ද්රයකට ලබා ගෙන, පෙරහන් කොට රටටම එතැනින් බදීම එදත් අදත් එසේම කර ගෙන යනවා.

මේ ක්රියාදාමය තුළ ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන් මා සම කළේ කුඩා තේ වතු හිමිකරුවන්ටයි. අක්කර 10ට වඩා අඩු බිම්වල තේ වවන මොවුන් ලක්ෂ 4ක් පමණ සිටිනවා. 2013 මෙරට සමස්ත තේ නිපැයුමෙන් 60%ක් වගා කළේ ඔවුන්.

තමන්ගේ තේ දළු අවට තිබෙන ලොකු තේ වත්තකට විකිණීම ඔවුන්ගේ ක්රමයයි. එතැනින් ඔබ්බට තම ඵලදාව ගැන පාලනයක් ඔවුන්ට නැහැ.

මේ උපමිතිය මා සඳහන් කළ විට මගේ සභාවේ සිටි එක් ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදියෙක් කීවේ තමන් සුළු තේ වතු හිිමියන්ටත් වඩා අසරණ බවයි. තේ දළු විකුණා ගැනීම සාමාන්යයෙන් ප්රශ්නයක් නොවෙතත්, තමන් සම්පාදනය කරන පුවත් හා රූපවලින් භාවිතයට ගැනෙන්නේ (හා ගෙවීම් ලබන්නේ) සමහරකට පමණක් බව ඔහු කියා සිටියා.

මෙරට මාධ්ය කර්මාන්තය සමස්තයක් ලෙස පර්යේණාත්මකව හදාරමින් සිටින මා මතු කළ ඊළඟ ප්රශ්නය මෙයයි. තේ කර්මාන්තයේ පිළිගත් ආකෘතියට අභියෝග කළ මෙරිල් ප්රනාන්දුට සමාන්තරව මාධ්ය කර්මාන්තයේ මුල් බැස ගත් ආකෘතිය අභියෝගයට ලක් කරන්නේ කවුද?

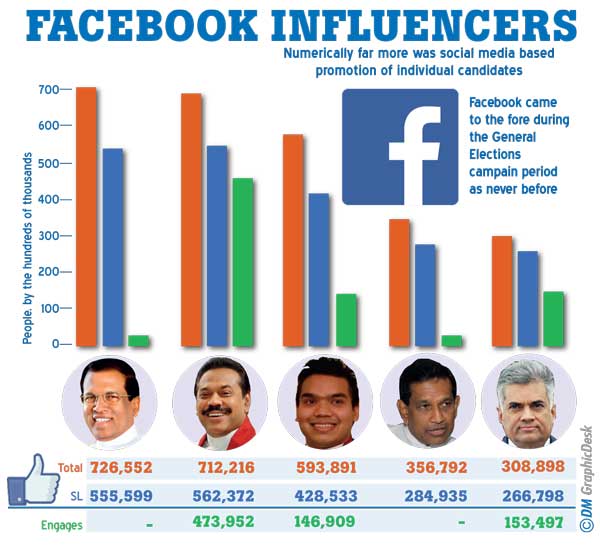

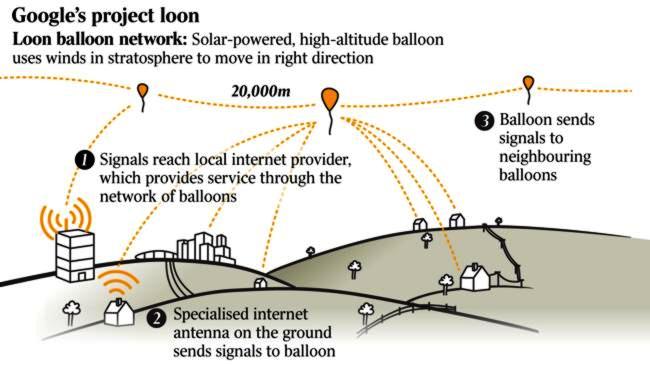

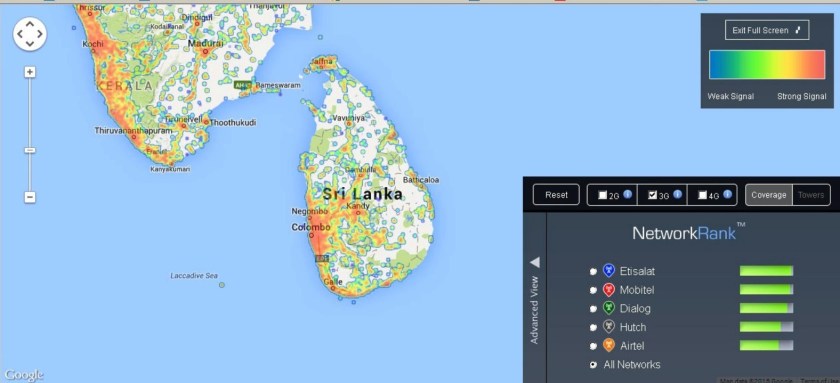

යම් තාක් දුරට මෙය පුරවැසි මාධ්යවේදීන් කරනවා. බ්ලොග් ලේඛකයන්, සමාජ ජාල මාධ්ය භාවිත කරන්නන් ප්රධාන ප්රවාහයේ මාධ්ය ගැන නොතකා කෙලින්ම තම තොරතුරු, අදහස් හා රූප ලොවට මුදා හරිනවා. රටේ ජනගහනයෙන් 20%ක් ඉන්ටර්නෙට් භාවිත කරන නිසා මෙය තරමක් දුරට සීමිත වූවත් (මා මීට පෙර විග්රහ කර ඇති පරිදි) එසේ සම්බන්ධිත වූවන් හරහා සමාජයේ තව විශාල සංඛ්යාවකට එම තොරතුරු ගලා යනවා.

මෙය දිගු කාලීනව ප්රධාන ප්රවාහයේ මාධ්යවලට අභියෝගයක්. එහෙත් අපේ බොහෝ මාධ්ය එය හරිහැටි වටහාගෙන නැහැ. ඔවුන් තවමත් සිටින්නේ ලිප්ටන් ආකෘතියේ මානසිකත්වයකයි.

හැකි පමණට වෙබ් හරහා තම තොරතුරු හා රූප මුදාහැරීම සමහර ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන් ආරම්භ කොට තිබෙනවා. උදාහරණ ලෙස මා ගෙන හැර දැක්වූයේ ගාල්ලේ බෙහෙවින් සක්රීය හා උද්යෝගීමත් මාධ්යවේදී සජීව විජේවීරයි. ඔහු ෆේස්බුක් හරහා බොහෝ දේ බෙදා ගන්නා අතර Ning.com නම් සමාජ මාධ්ය වේදිකාව හරහා ගාලූ පුරවැසියෝ නම් එකමුතුවක්ද කලක් කර ගෙන ගියා.

මේ අතර මාතර දිස්ත්රික්කයේ ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන් 70 දෙනෙකු එක් වී Journalist in Matara නම් විවෘත ෆේස්බුක් පිටුවක් කරනවා. ඒ හරහා තමන් එකතු කරන තොරතුරු හා රූප බෙදා ගන්නවා. ප්රාදේශීය වශයෙන් වැදගත් එහෙත් සැම විටම ජාතික මාධ්යවලට අදාළ නොවන බොහෝ දේ එහි හමු වනවා.

මෙබඳු තවත් උදාහරණ වෙනත් ප්රදේශවලද සිංහලෙන් හා දෙමළෙන් තිබෙනවා. එහෙත් මේ කිසිවකුට තවම ඒ හරහා ජීවිකාව උපයා ගන්නට බැහැ. හොඳ මාධ්ය අංග සඳහා පාඨකයන් කැමති ගානක් ගෙවා නඩත්තු කරන ආකාරයේ සමූහ සම්මාදම් නැතිනම් ජනතා ආයෝජන ක්රමවේදයන් (crowd-funding) වඩාත් දියුණු රටවල දැන් තිබෙනවා. එම ආකෘති අප අධ්යයනය කොට හැකි නම් අදාළ කර ගත යුතුයි.

මේ කිසිවක් ප්රධාන ප්රවාහයේ මාධ්යවලට ඍජුව අභියෝග කිරීමක් නොවේ. එහෙත් නිසි පිළි ගැනීමකට හෝ සාධාරණ ගෙවීමකට ලක් නොවී සිටින ප්රාදේශීය මාධ්යවේදීන් තාක්ෂණය හරහාවත් බලාත්මක කොට ඒ හරහා අපේ තොරතුරු සමාජය වඩාත් සවිමත් කළ හැකි නම් කොතරම් අපූරුද?