Trends like ultra-nationalistic media, hate speech and fake news have all been around for decades — certainly well before the web emerged in the 1990s. What digital tools and the web have done is to ‘turbo-charge’ these trends.

This is the main thrust of this week’s Ravaya column, published on 1 July 2018, where I capture some discussions and debates at the 11th Deutsche Welle Global Media Forum (GMF), held in Bonn, Germany, from 11 to 13 June 2018.

I was among the 2,000+ media professionals and experts from over 100 countries who participated in the event. Across many plenaries and parallel sessions, we discussed a whole range of issues related to politics and human rights, media development and innovative journalism concepts.

On 13 June 2018, I moderated a session on “Digitalization and polarization of the media: How to overcome growing inequalities and a divided public” which was organised by the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (ifa) or Institute for Foreign Relations, a century old entity located in Bonn. Most of the column draws on my own panel’s explorations, about which I have already written in English here: DW Global Media Forum 2018: Moderating panel on ‘Digitalization and Polarization of the Media’

2018 ජූනි 11-13 තෙදින තුළ ජර්මනියේ බොන් නුවර පැවති ගෝලීය මාධ්ය සමුළුවේ (Global Media Forum) එක් සැසි වාරයක් මෙහෙය වීමට මට ඇරයුම් ලැබුණා.

2007 සිට වාර්ෂිකව පවත්වන මේ සමුළුව සංවිධානය කරන්නේ ජර්මනියේ ජාත්යන්තර විද්යුත් මාධ්ය ආයතනය වන ඩොයිෂවෙල (Deutsche Welle) විසින්.

මෙවර සමුළුවට රටවල් 100කට අධික සංඛ්යාවකින් 2,000 ක් පමණ මාධ්යවේදීන්, මාධ්ය කළමනාකරුවන් හා මාධ්ය පර්යේෂකයන් සහභාගී වුණා. මහා මාධ්ය මෙන්ම නව මාධ්ය ඇති කරන බලපෑම් හා අභියෝග ගැන විවෘතව කතාබහ කිරීමට එය හොඳ වේදිකාවක් වූවා.

අපේ සමහරුන් පොදුවේ ‘බටහිර රටවල්’ යයි කීවාට සැබෑ ලෝකයේ එබඳු තනි ගොඩක් නැහැ. බටහිරට අයත් ඇමරිකා එක්සත් ජනපදය සමඟ බොහෝ කාරණාවලදී යුරෝපීය රටවල් එකඟ වන්නේ නැහැ.

එසේම යුරෝපා සංගමය ලෙස පොදු ආර්ථීක හවුලක් යුරෝපීය රටවල් 28ක් ඒකරාශී කළත් එම රටවල් අතරද සංස්කෘතික හා දේශපාලනික විවිධත්වය ඉහළයි.

ලිබරල් ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී රාමුවක් තුළ මෙම විවිධත්වය නිිසා නොයෙක් බටහිර රාජ්යයන් මාධ්ය ප්රතිපත්ති ගැන දක්වන නිල ස්ථාවරයන් අතර වෙනස්කම් තිබෙනවා. බොන් නුවරදී දින තුනක් තිස්සේ අප මේ විවිධත්වය සවියක් කර ගනිමින් බොහෝ දේ සාකච්ඡා කළා.

ලෝකයේ රටවල් කෙමෙන් ඩිජිටල්කරණය වන විට ඒ හරහා උදා වන නව අවස්ථාවන් මෙන්ම අභියෝග ගැනත් සංවාද රැසක් පැවැත් වුණා.

යුරෝපා හවුලේ ඩිජිටල් ආර්ථීකයන් හා සමාජයන් පිළිබඳ කොමසාරිස්වරි වන මරියා ගේබ්රියල් මේ ගැන ආරම්භක සැසියේ දී හොඳ විග්රහයක් කළා.

පොදුවේ වෙබ් අවකාශයත්, විශේෂයෙන් ඒ තුළ හමු වන සමාජ මාධ්යත් මානව සමාජයන් වඩාත් ප්රජාතන්ත්රීය කිරීමට හා සමාජ අසමානතා අඩු කිරීමට බෙහෙවින් දායක විය හැකි බව පිළි ගනිමින් ඇය කීවේ මෙයයි.

”එහෙත් අද ගෝලීය සමාජ මාධ්ය වේදිකා බහුතරයක් මේ යහපත් විභවය සාක්ෂාත් කර ගැනීමට දායක වනවා වෙනුවට දුස්තොරතුරු (disinformation) හා ව්යාජ පුවත් එසැනින් බෙදා හැරීමට යොදා ගැනෙනවා. මෙය සියලු ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී සමාජයන් මුහුණ දෙන ප්රබල අභියෝගයක්. සමහර සමාජ මාධ්ය වේදිකා මේ වන විට ප්රධාන ධාරාවේ මාධ්යවල කාරියම කරනවා. එනම් කාලීන තොරතුරු එක් රැස් කිරීම හා බෙදා හැරීම. එහෙත් ඔවුන් එසේ කරන විට සංස්කාරක වගකීමක් (editorial responsibility) නොගැනීම නිසා ව්යාකූලතා මතු වනවා.”

ඇගේ මූලික නිර්දේශයක් වූයේ සමාජ මාධ්ය වේදිකා නියාමනය නොව මාධ්ය බහුවිධත්වය (media pluralism) ප්රවර්ධනය කළ යුතු බවයි.

රටක මාධ්ය බහුවිධත්වය පවතී යයි පිළිගන්නේ මාධ්ය ආයතන හා ප්රකාශන/නාලිකා ගණන වැඩි වූ පමණට නොවේ.

තනි හිමිකරුවකුගේ හෝ ටික දෙනකුගේ හිමිකාරීත්වය වෙනුවට විසිර ගිය හිමිකාරිත්වයන් තිබීම, අධිපතිවාදී මතවාද පමණක් නොව පුළුල් හා විවිධාකාර මතවාදයන්ට මාධ්ය හරහා ඇති තරම් අවකාශ ලැබීම, හා සමාජයේ කොන්ව සිටින ජන කොටස්වලට ද සිය අදහස් ප්රකාශනයට මාධ්යවල ඇති තරම් ඉඩක් තිබීම වැනි සාධක ගණනාවක් තහවුරු වූ විට පමණක් මාධ්ය බහුවිධත්වය හට ගන්නවා. (මේ නිර්නායක අනුව බලන විට අපේ රටේ මාධ්ය රැසක් ඇතත් බහුවිධත්වය නම් නැහැ.)

ඩිජිටල් මාධ්ය බහුල වෙමින් පවතින අද කාලේ ප්රධාන ධාරාවේ මාධ්යවල කෙතරම් බහුවිධත්වයක් පැවතීම තීරණාත්මකද? මේ ප්රශ්නයට පිළිතුරු සංවාද හරහා මතු වුණා.

මේ වන විට ලොව ජනගහනයෙන් අඩකටත් වඩා ඉන්ටර්නෙට් භාවිතා කළත්, පුවත් හා කාලීන තොරතුරු මූලාශ්රයන් ලෙස ටෙලිවිෂන් හා රේඩියෝ මාධ්යවල වැදගත්කම තවමත් පවතිනවා. (පුවත් හා සඟරා නම් කෙමෙන් කොන් වී යාම බොහෝ රටවල දැකිය හැකියි.)

මේ නිසා මාධ්ය බහුවිධත්වය තහවුරු කරන අතර මාධ්ය විචාරශීලීව පරිභෝජනය කිරීමට මාධ්ය සාක්ෂරතාවයත් (media literacy), ඩිජිටල් මාධ්ය නිසි ලෙස පරිහරණයට ඩිජිටල් සාක්ෂරතාවයත් (digital literacy) අත්යවශ්ය හැකියා බවට පත්ව තිබෙනවා.

ඩිජිටල් සාක්ෂරතාවය යනු හුදෙක් පරිගණක හා ස්මාර්ට් ෆෝන් වැනි ඩිජිටල් තාක්ෂණ මෙවලම් තනිවම භාවිතා කිරීමේ හැකියාව පමණක් නොව ඩිජිටල් අන්තර්ගතයන් විචාරශීලීව ග්රහණය කිරීමේ හැකියාව ද එහි වැදගත් අංගයක් බව සමුළුවේ යළි යළිත් අවධාරණය කෙරුණා.

මරියා ගේබ්රියල් මෑත කාලයේ යුරෝපයේ කළ සමීක්ෂණයක සොයා ගැනීම් උපුටා දක්වමින් කීවේ වයස 15-24 අතර යුරෝපීය ළමුන් හා තරුණයන් අතර ව්යාජ පුවතක් හා සැබෑ පුවතක් වෙන් කර තේරුම් ගැනීමේ හැකියාව තිබුණේ 40%කට බවයි.

එයින් පෙනෙන්නේ යම් පිරිස් විසින් දුස්තොරතුරු සමාජගත කර මැතිවරණ, ජනමත විචාරණ හා වෙනත් තීරණාත්මක සමාජයීය ක්රියාදාමයන් අවුල් කිරීමේ අවදානමක් පවතින බවයි.

මෙබැවින් මාධ්ය සාක්ෂරතාවය හා ඩිජිටල් සාක්ෂරතාවය වැඩි කළ යුත්තේ තනි පුද්ගලයන්ගේ කුසලතා වර්ධනයට පමණක් නොවෙයි. අසත්යන්, අර්ධ සත්යන්, හා කුමන්ත්රණවාදී තර්ක හරහා ප්රජාතාන්ත්රීය සමාජයන් නොමඟ යැවීමටත්, ඒ හරහා රාජ්යයන් අස්ථාවර කිරීමටත් එරෙහිව සමාජයේ ප්රතිශක්තිය ගොඩ නැංවීමටයි.

මා මෙහෙය වූ සැසි වාරයේ අප මෙම සමාජයීය අභියෝගය ගැන විද්වත් මෙන්ම ප්රායෝගික ලෙසත් සාකච්ඡා කළා.

මගේ සැසියේ කථීකයන් වූයේ ජර්මනියේ බර්ලින් නුවර ෆ්රී සරසවියේ දේශපාලන විද්යාඥ ආචාර්ය කුර්ඩ් නුප්ෆර් (Dr Curd Knupfer), ඇමරිකාවේ ඉලෙක්ට්රොනික් ෆ්රන්ටියර් පදනමේ භාෂාණ නිදහස පිළිබඳ අධ්යක්ෂිකා ජිලියන් යෝක් (Jillian York) සහ විකිමීඩියා ජර්මන් පදනමේ නියෝජ්ය විධායක අධ්යක්ෂ ක්රිස්ටියන් හුම්බොග් (Christian Humborg) යන තිදෙනායි.

සැසිවාරය අරඹමින් මා මෙසේ ද කීවා:

”වෙබ්ගත අවකාශයන් හරහා වෛරී කථනය හා ව්යාජ පුවත් ගලා යාම ගැන අද ලොකු අවධානයක් යොමු වී තිබෙනවා. වර්ගවාදී හා වෙනත් අන්තවාදී පිරිස් සමාජ මාධ්ය වේදිකා හරහා ආන්තික සන්නිවේදනය කරමින් සිටිව බවත් අප දන්නවා. එහෙත් මේ ප්රවනතා එකක්වත් ඉන්ටර්නෙට් සමඟ මතු වූ ඒවා නොවෙයි. 1990 දශකයේ වෙබ් අවකාශය ප්රචලිත වීමට දශක ගණනාවකට පෙරත් අපේ සමාජයන් තුළ මේවා සියල්ලම පැවතියා. වෙබ් පැතිරීමත් සමග සිදුව ඇත්තේ මේ ආන්තික ප්රවාහයන්ට නව ගැම්මක් ලැබීමයි. එනිසා දැන් අප කළ යුතුව ඇත්තේ භෞතික ලෝකයේ වුවත්, සයිබර් අවකාශයේ වුවත්, වෛරී කථනය, ව්යාජ පුවත් හා ආන්තික සන්නිවේදනවලට එරෙහිව සීරුවෙන් හා බුද්ධිමත්ව ප්රතිචාර දැක්වීමයි. එසේ කිරීමේදී අප සැවොම ඉහළ වටිනාකමක් දෙන භාෂණයේ නිදහස රැකෙන පරිදි ක්රියා කළ යුතුයි. අප නොරිසි දේ කියන අයටත් භාෂණ නිදහස එක සේ හිමි බව අප කිසි විටෙක අමතක නොකළ යුතුයි.”

එසේම තව දුරටත් ‘නව මාධ්ය’ හා ‘සම්ප්රදායික මාධ්ය’ හෙවත් ‘ප්රධාන ධාරාවේ මාධ්ය’ කියා වර්ගීකරණය කිරීම ද එතරම් අදාල නැති බව මා පෙන්වා දුන්නා. සමහර සමාජවල (උදා: කොරියාව, සිංගප්පූරුව) ප්රධාන ධාරාව බවට ඩිජිටල් මාධ්ය දැනටමත් පත්ව තිබෙනවා. එසේම වසර 20කට වැඩි ඉතිහාසයක් ඇති ඩිජිටල් මාධ්ය තව දුරටත් එතරම් අලුත් හෝ ‘නව මාධ්ය’ වන්නේ ද නැහැ.

ඒ නිසා ලේබල්වලට වඩා වැදගත් සමස්ත තොරතුරු සන්නිවේදන තාක්ෂණයන්ම ජන සමාජ වලට කරන බලපෑම පොදුවේ අධ්යයනය කිරීමයි.

සමාජ මාධ්ය වේදිකා හරහා නොයෙක් පුද්ගලයන් පළකරන හෝ බෙදාගන්නා (ෂෙයාර් කරන) අන්තර්ගතයන් පිළිබඳ එකී වේදිකා හිමිකාර සමාගම් කෙතරම් වගකිව යුතුද?

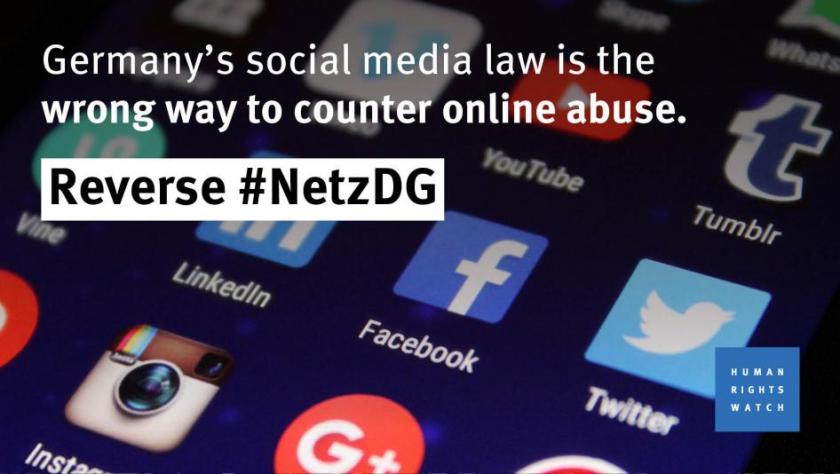

2018 ජනවාරි 1 වැනිදා සිට ජර්මනියේ ක්රියාත්මක වන නව නීතියකට අනුව සමාජ මාධ්ය වේදිකාවක වෛරී ප්රකාශ යමකු සන්නිවේදනය කෙරුවොත් පැය 24ක් ඇතුළත එය ඉවත් කිරීමේ වගකීම් අදාළ වේදිකා පරිපාලකයන්ට භාර කැරෙනවා. එසේ නොකළොත් යූරෝ මිලියන් 50 (අමෙරිකානු ඩොලර් මිලියන් 62ක්) දක්වා දඩ නියම විය හැකියි.

සද්භාවයෙන් යුතුව හඳුන්වා දෙන ලද නව නීතියේ මාස කිහිපයක ක්රියාකාරීත්වය කෙසේදැයි මා විමසුවා. ජර්මන් කථීකයන් කීවේ වෛරී ප්රකාශ ඉවත් කිරීමට සමාජ මාධ්ය වේදිකා මහත් සේ වෙර දැරීම තුළ වෛරී නොවන එහෙත් අසම්මත, විසංවාදී හා ජනප්රිය නොවන විවිධ අදහස් දැක්වීම්ද යම් ප්රමාණයක් ඉවත් කොට ඇති බවයි.

දේශපාලන විවේචනයට නීතියෙන්ම තහවුරු කළ පූර්ණ නිදහස පවතින ජර්මනිය වැනි ලිබරල් ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී රටකට මෙම නව නීතිය දරුණු වැඩි බවත්, එය සංශෝධනය කොට වඩාත් ලිහිල් කළ යුතු බවත් මෑතදී පත්වූ නව ජර්මන් රජය පිළිගෙන තිබෙනවා.

නව නීතිය යටතේ අසාධාරණ හා සීමාව ඉක්මවා ගොස් ඉවත් කරනු ලැබූ වෙබ් අන්තර්ගතයන් අතර දේශපාලන හා සමාජයීය උපහාසය පළ කරන ප්රකාශනද තිබෙනවා. සමාජ ප්රශ්නයක් ගැන ජන අවධානය යොමු කිරීමට හාසකානුකරණය (parody) පළ කිරීම සමහර හාස්යජනක (satire) ප්රකාශනවල සිරිතයි.

එහෙත් නව නීතියේ රාමුව වුවමනාවටත් වඩා තදින් ක්රියාත්මක කළ ට්විටර් හා ෆේස්බුක් වැනි වේදිකාවල පරිපාලකයෝ මෙවන් හාස්යජනක හෝ උපහාසාත්මක අන්තර්ගතයද ජර්මනිය තුළ දිස්වීම වළක්වා තිබෙනවා.

උපහාසය ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී අවකාශයේ වැදගත් අංගයක්. එයට වැට බඳින නීතියක් නැවත විමර්ශනය කළ යුතු බව ජර්මන් පර්යේෂකයන්ගේ මතයයි. (සමාජ මාධ්ය නියාමනය ගැන මෑත සතිවල කතා කළ ලක් රජයේ සමහර උපදේශකයෝ ජර්මන් නීතිය උදාහරණයක් ලෙස හුවා දැක්වූ බව අපට මතකයි.)

අපේ සංවාදයේ එකඟ වූ මූලධර්මයක් නම් සමාජ ව්යාධියකට කරන නියාමන ‘ප්රතිකාරය’ ව්යාධියට වඩා බරපතළ විපාක මතු කරන්නේ නම් එය නිසි ප්රතිකාරයක් නොවන බවයි.

සමුළුව පැවති තෙදින පුරා විවිධ කථීකයන් මතු කළ තවත් සංකල්පයක් වූයේ ඩිජිටල් හා වෙබ් මාධ්ය අතිවිශාල සංඛ්යාවක් බිහි වීම හරහා තොරතුරු ග්රාහකයන් එන්න එන්නම කුඩා කොටස්/කණ්ඩායම්වලට බෙදෙමින් සිටින බවයි.

රේඩියෝ හා ටෙලිවිෂන් නාලිකා සංඛ්යාව වැඩිවීම සමග දශක දෙක තුනකට පෙර පටන් ගත් මේ කඩ කඩ වීම (audience fragmentation) වෙබ් අඩවි හා සමාජ මාධ්ය ප්රචලිත වීම සමග බෙහෙවින් පුළුල්ව තිබෙනවා.

තමන් රිසි මති මතාන්තර පමණක් ඇසිය හැකි, දැකිය හැකි වෙබ් අඩවි හෝ සමාජ මාධ්ය පිටු වටා ජනයා සංකේන්ද්රණය වීම ‘filter bubbles‘ ලෙස හඳුන් වනවා. ඍජු පරිවර්තනයක් තවම නැතත්, තම තමන්ගේ මතවාදී බුබුලු තුළම කොටු වීම යැයි කිව හැකියි. මෙවන් ස්වයං සීමාවන්ට පත් වූ අයට විකල්ප තොරතුරු හෝ අදහස් ලැබෙන්නේ අඩුවෙන්.

පත්තර, ටෙලිවිෂන් බලන විට අප කැමති මෙන්ම උදාසීන/නොකැමති දේත් එහි හමු වනවා. ඒවාට අප අවධානය යොමු කළත් නැතත් ඒවා පවතින බව අප යන්තමින් හෝ දන්නවා. එහෙත් තමන්ගේ සියලු තොරතුරු හා විග්රහයන් වෙබ්/සමාජ මාධ්යවල තෝරා ගත් මූලාශ්ර හරහා ලබන විට මේ විසංවාද අපට හමු වන්නේ නැහැ.

එහෙත් අපේ සංවාදයට නව මානයක් එක් කරමින් මා කීවේ ඔය කියන තරම් ඒකාකාරී මූලාශ්රවලට කොටු වීමක් අපේ වැනි රටවල නම් එතරම් දක්නට නැති බවයි. විවිධාකාර මූලාශ්ර පරිශීලනය කොට යථාර්ථය පිළිබඳ සාපේක්ෂව වඩාත් නිවැරදි චිත්රයක් මනසේ ගොඩ නගා ගන්නට අප බොහෝ දෙනෙක් තැත් කරනවා.

ඔක්ස්ෆර්ඩ් සරසවියේ ඉන්ටර්නෙට් පර්යේෂණායතනය (Oxford Internet Institute) 2018 මාර්තුවේ පළ කළ සමීක්ෂණයකින්ද මෙබන්දක් පෙන්නුම් කරනවා. වයස 18ට වැඩි, ඉන්ටර්නෙට් භාවිත කරන බ්රිතාන්ය ජාතිකයන් 2000ක සාම්පලයක් යොදා ඔවුන් කළ සමීක්ෂණයෙන් හෙළි වූයේ තනි හෝ පටු වෙබ් මූලාශ්රයන්ට කොටු වීමේ අවදානම තිබුණේ සාම්පලයෙන් 8%කට පමණක් බවයි.

එනම් 92%ක් දෙනා බහුවිධ මූලාශ්ර බලනවා. මතු වන තොරතුරු අනුව තමන්ගේ අදහස් වෙනස් කර ගැනීමට විවෘත මනසකින් සිටිනවා.

බොන් මාධ්ය සමුළුවේ අප එකඟ වූයේ ජනමාධ්ය හා සන්නිවේදන තාක්ෂණයන් සමාජයට, ආර්ථීකයට හා දේශපාලන ක්රියාදාමයන්ට කරන බලපෑම් ගැන සමාජ විද්යානුකූලව, අපක්ෂපාත ලෙසින් දිගටම අධ්යයනය කළ යුතු බවයි. ආවේගයන්ට නොව සාක්ෂි හා විද්වත් විග්රහයන්ට මුල් තැන දෙමින් නව ප්රතිපත්ති, නීති හා නියාමන සීරුවෙන් සම්පාදනය කළයුතු බවයි.

අමෙරිකානු සමාගම්වලට අයත් ෆේස්බුක්, ට්විටර් හා ඉන්ස්ටර්ග්රෑම් වැනි වේදිකා සිය ජන සමාජයන්හි මහත් සේ ප්රචලිත වී තිබීම ගැන සමහර යුරෝපීය ආණ්ඩුවල එතරම් කැමැත්තක් නැහැ. එහෙත් ලිබරල් ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී මූලධර්මවලට හා මානව නිදහසට ගරු කරන රාජ්යයන් ලෙස ඔවුන් වෙබ් වාරණයට, අනවශ්ය ලෙස නියාමනයට විරුද්ධයි. ලිහිල් ලෙසින්, අවශ්ය අවම නියාමනය ලබා දීමේ ක්රමෝපායයන් (light-touch regulation strategies) ඔවුන් සොයනවා.

මේ සංවාද පිළිබඳව අවධියෙන් සිටීම හා යුරෝපීය රටවල අත්දැකීම් අපට නිසි ලෙස අදාළ කර ගැනීම වැදගත්. අපේ ආදර්ශයන් විය යුත්තේ ලිබරල් ප්රජාතන්ත්රීය රටවල් මිස දැඩි මර්දනකාරී චීනය වැනි රටවල් නොවේ.