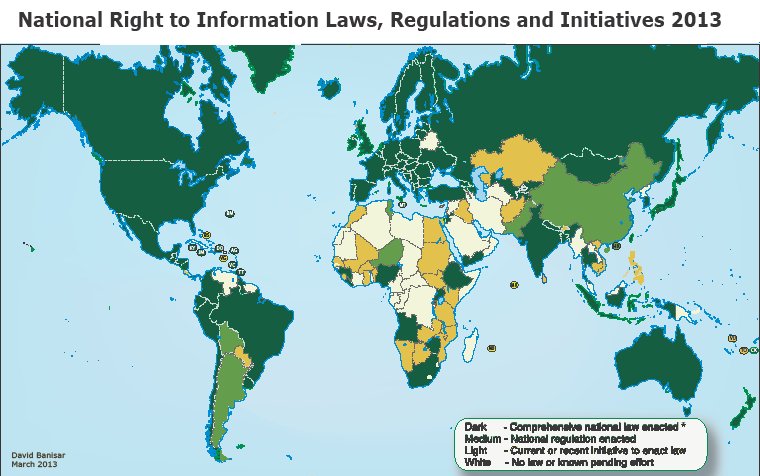

After many years of advocacy by civil society groups and journalists, Sri Lanka is set to soon adopt a law guaranteeing citizens’ Right to Information (RTI, also known as freedom of information laws in some countries). With that, we will join over 100 other countries that have introduced such progressive laws.

The first step is already taken. The 19th Amendment to the Constitution, passed in Parliament in April 2015, made the right to information a fundamental right. The Right to Information Act is meant to institutionalize the arrangement – i.e. put in place the administrative arrangement where a citizen can seek and receive public information.

RTI signifies unleashing a new potential, and a major change in status quo. First, we need to shake off a long historical legacy of governments not being open or accountable to citizens.

In this week’s Ravaya column, (appearing in issue of 22 Nov 2015), I explore how RTI can gradually lead to open government. I also introduce the 9 key principles of RTI.

I have covered the same ground in English here:

20 Nov 2015: Right to Information should be a step towards Open Government

තොරතුරු දැනගැනීමේ අයිතිය තහවුරු කැරෙන නීතිය සම්මත වන තුරු මේ වසර පුරාම අපි බලා සිටිනවා. ‘අද නෑ හෙට’ වගේ වැඩක්!

යහපාලනයේ එක් ප්රධාන පොරොන්දුවක් වූයේද තොරතුරු අයිතියයි. එක් අඩක් ඉටු වී තිබෙනවා කිව හැකියි. මන්ද 2015 අපේ්රල් 28දා පාර්ලිමේන්තුවේ සම්මත වූ 19 වන ව්යවස්ථා සංශෝධනයේ තොරතුරු අයිතිය මූලික අයිතිවාසිකමක් ලෙස පැහැදිලිවම පිළිගෙන තිබෙනවා.

මේ අයිතිය ප්රායෝගිකව ක්රියාත්මක කිරීමට තොරතුරු නීතිය අවශ්යයි. ඒ හරහා සමස්ත රාජ්ය පරිපාලන තන්ත්රයේම වෙනසක් සිදු කැරෙනවා. හැකි තාක් මහජනයාට රහසිගතව කටයුතු කිරීමේ ඓතිහාසික සම්ප්රදායෙන් මිදී වඩාත් විවෘත හා තොරතුරු බෙදා ගන්නා රාජ්ය පාලනයකට යොමුවීමේ ක්රමවේදයක් මේ නීතිය හරහා හඳුන්වා දීමට නියමිතයි.

තොරතුරු නීති කෙටුම්පත් හරිහැටි හදා ගන්නට මෙතරම් කල් ගත වන්නේ ඇයි?

මනා නීති සම්පාදනය සඳහා ආදර්ශයට ගත හැකි තොරතුරු නීති දකුණු ආසියාවේත්, ඉන් පිටතත් රටවල් 100ක තිබෙනවා. මේ නිසා හැම නීති වැකියක්ම අලූතෙන්ම වචන ගැලපිය යුතු නැහැ. තොරතුරු අයිතිය පිළිබඳ ජාත්යන්තර යහ සම්ප්රදායන් ගැන බොහෝ ලේඛනද තිබෙනවා. යුනෙස්කෝ ආයතනය මේ ගැන විශේෂ අවධානය යොමු කොට තිබෙනවා.

මෙතැන ඇත්තේ නීති හැකියාවන් පිළිබඳ ගැටලූවක් නොව ආකල්පමය එල්බ ගැනීම් බවයි දැන ගන්නට තිබෙන්නේ. අපේ නීතිපති දෙපාර්තමේන්තුව හා නීති කෙටුම්පත් දෙපාර්තමේන්තුව බෙහෙවින් ගතානුගතික පදනමක පිහිටා ක්රියාකිරීම නිසා තොරතුරු බෙදා ගන්නවාට වඩා බදා ගන්නට නැඹුරු වූ නීතියක් බිහි වීමේ අවදානම තිබෙනවා. මේ අවසාන අදියරේදී ස්වාධීන නීති විශාරදයන් හා සිවිල් සමාජ ක්රියාකාරිකයන් අවදියෙන් හා අවධානයෙන් සිටීම අත්යවශ්යයි. නැතිනම් එතරම් ප්රයෝජනයක් ගත නොහැකි නාමමාත්රික තොරතුරු නීතියක් සම්මත විය හැකියි.

රාජ්ය දෙපාර්තමේන්තු දෙකක පටු මානසිකත්වයට වඩා පුළුල් අභියෝගයක්ද මෙහිදී මා දකිනවා. එනම් අපේ ඉතා වැඩවසම් ඓතිහාසික උරුමය හා නූතනත්වය අතර අරගලයයි.

සියවස් 25ක ලිඛිත ඉතිහාසයක් ඇති අපේ රටේ විවෘත හා මහජනතාවට වගකියන ආණ්ඩුකරණයක් ඉතා මෑතක් වන තුරු කිසි දිනෙක පැවතියේ නැහැ. මැග්නා කාර්ටා (Magna Carta) වැනි සම්මුතියක් හරහා අපේ රජුන්ගේ බලතල කිසි ලෙසකින් හෝ සමනය වූයේ ද නැහැ.

1 May 2015: සිවුමංසල කොලූගැටයා #217: වසර 800කට පෙර යහපාලන අඩිතාලම දැමූ මැග්නා කාටාව

සීමාන්තික බලතල සහිත රජවරුන් අපේ රට පාලනය කළ වසර 2,000ක පමණ කාලයක් තුළ රටේ කිසිදු පරිපාලන තොරතුරක් (හෝ වෙනත් කිසිම අයිතිවාසිකමක්) ඉල්ලීමේ වරම ජනතාවට තිබුණේ නැහැ. අපේ පැරැන්නෝ යටත් වැසියන් මිස කිසි දිනෙක පුරවැසියන් වූයේ නැහැ.

ඉන්පසු එළැඹුණු යටත් විජිත පාලන යුගවලත් එම පාලකයන් කිසි විටෙක තොරතුරු හෙළි කිරීමට බැඳී සිටියේ නැහැ. බි්රතාන්ය පාලන තන්ත්රය තුළ ලේඛන පවත්වා ගැනීම ඉතා හොඳින් සිදු කළත්, ඒ ලේඛන ඔවුන්ගේ ලන්ඩනයේ යටත් විජිත පරිපාලකයන්ට මිස මෙරට සාමාන්ය ජනයාට පරිශීලනය කළ හැකි වූයේ නැහැ. (මේ වාර්තා දැන් නම් බි්රතාන්ය කෞතුකාගාරයේ ඕනෑම කෙනෙකුට කියවිය හැකියි. බි්රතාන්ය පාලන යුගය දැඩි ලෙස විවේචනය කරන හැම දෙනෙකුම පාහේ තම මූලාශ්ර යොදා ගන්නේ එම වාර්තායි.)

නිදහසින් පසුව රට පාලනය කළ අපේම ආණ්ඩුත් බොහෝ දුරට රටවැසියන්ට තොරතුරු කැමැත්තෙන් දෙනවා වෙනුවට හැකි තාක් වසන් කිරීමේ සම්ප්රදාය දිගටම ගෙන ගියා. යටත් විජිත සමයේ ආභාෂය මෙන්ම ඉතිහාසයේ කිසි දිනෙක රටවැසියාට විවෘත වූ ආණ්ඩුකරණයක් (Open Government) නොතිබීම ද එයට හේතු වූවා විය හැකියි.

මෙයින් අදහස් කැරෙන්නේ නිදහසින් පසු අපට තිබූ සියලූ රජයන් දුර්දාන්ත හෝ දරදඬු පාලනයන් වීය කියා නොවෙයි. ඇතැම් ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී නායකයන් පවා රට වැසියන්ට සැලකුවේ හරියට දෙමවුපියන් ළමයින් දෙස බලන ආකල්පයට සමාන මානසිකත්වයකින්. වැසියන් රැක බලා ගෙන ඔවුන්ට අවශ්ය සම්පාදන කර දීම විනා ඔවුන් ස්වාධීනව සිතන පතන “වැඩිහිටියන්” වීම අවශ්ය යැයි ඩී එස් හා ඩඩ්ලි වැනි නායකයන්ට නොසිතෙන්නට ඇති.

සමාජ ක්රියාකාරික හා ලේඛක ගාමිණී වියන්ගොඩගේ මතය නම් තොරතුරු උවමනාවෙන්ම රටවැසියන්ට නොදී සිටින්නේ තොරතුරු හරහා රටවැසියන් බලාත්මක වන නිසායි. වසන් කළ යුතු අමිහිරි හා අශෝබන බොහෝ දේ හැම රාජ්ය පාලනයකම තිබෙන බවත්, මේ තොරතුරු පිට වීම හා ගලා යාම පවතින බල සංකේන්ද්රයන්ට බරපතල ප්රශ්නයක් බවත් ඔහු කියනවා.

කාලානුරූපව වෙනස් වෙන්නට කාලය ඇවිත්! අපේ ඓතිහාසික උරුමය කිසි දිනෙක විවෘත ආණ්ඩුකරණයකට නැඹුරු නොවූවත්, 21 වන සියවසේ යහපාලනයට හා ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදයට එය අත්යවශ්ය ගුණයක් ලෙස දැන් සැලකෙනවා.

විවෘත ආණ්ඩුකරණයේ සංකල්පය 18 වන සියවසේ බටහිර යුරෝපයේ පුනරුදය (Age of Enlightenment) වෙත දිවෙනවා. සීමාන්තික බලතල සහිත රාජාණ්ඩු වඩාත් බල තුලනයකට යටත් කළ යුතු බවටත්, මහජන මතයට සංවේදී ආණ්ඩුකරණයක් බිහි විය යුතු බවටත් ප්රංශ හා ජර්මන් දාර්ශනිකයන් තර්ක කිරීම ඇරඹුණේ ඒ සමයේයි.

මෙය නීතිගත කරමින් ලොව මුල්ම තොරතුරු නීතිය 1766දී හඳුන්වා දුන්නේ ස්වීඩනයයි. මාධ්ය නිදහස හා තොරතුරු අයිතිය නීතියෙන් තහවුරු කිරීම ඉන් පසු එළැඹි දශකවල බොහෝ බටහිර රටවල සිදු කෙරුණා. රාජ්ය පාලනයේ රහසිගත බව වඩ වඩාත් පටු පරාසයකට සීමා කිරීමෙන්, විවෘත බව සාමාන්යකරණය කිරීමට 20 වන සියවස පුරා පරිණත ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී රටවල නීතිමය, ප්රතිපත්තිමය මෙන්ම යහ සම්ප්රදායික පියවර ගෙන තිබෙනවා.

මේ ගෝලීය ඓතිහාසික පසුබිම තුළ මා තොරතුරු නීතිය දකින්නේ මෙරට සමස්ත ආණ්ඩුකරණය වඩාත් විවෘත හා මහජනතාවට වගකියන තත්ත්වයට පත් කරන්නට දායක වන එක් පියවරක් හැටියටයි.

මෙයට සමාන්තරව සමාලෝචනයට ලක් විය යුතු හා සංශෝධනය කළ යුතු තවත් නීති තිබෙනවා. 1955 අංක 32 දරණ රාජ්ය රහස් පනත එයින් ප්රමුඛයි. 1911දී බි්රතාන්යයේ සම්මත වූ නීතියක් ආශ්රයෙන් සම්පාදිත අපේ 1955 රාජ්ය රහස් නීතිය යල්පැන ගිය, නූතන ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී සම්ප්රදායන්ට කිසිසේත් නොගැළපෙන එකක්.

එහි රාජ්ය රහස් යන්න අනවශ්ය තරම් පුළුල්ව නිර්වචනය කැරෙන බවත්, එය නිදහසට කාරණයක් ලෙස දක්වමින් දශක ගණනාවක් පුරා රාජ්ය නිලධාරීන් සැබැවින්ම රහසිගත නොවිය යුතු බොහෝ තොරතුරු ද වසන් කරන බවත් නීති පර්යේෂකයන් කියනවා.

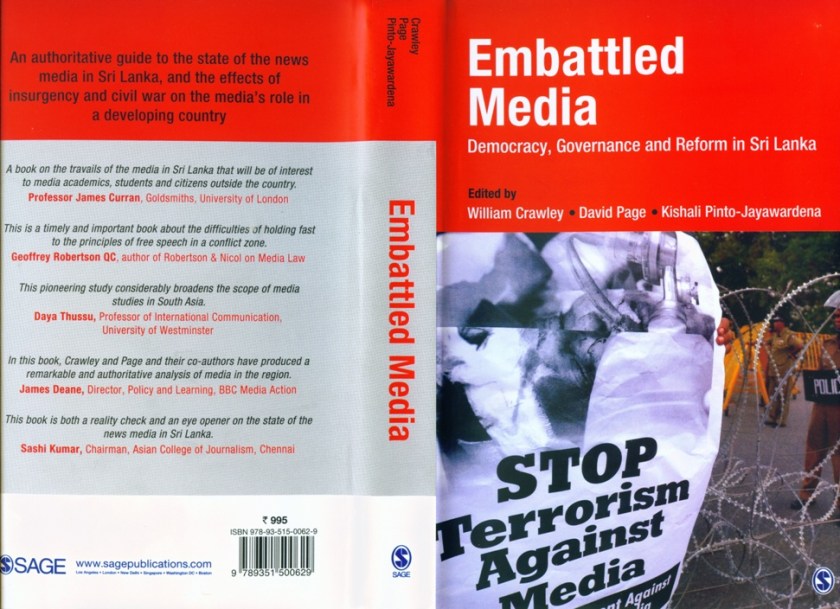

‘1911 රාජ්ය රහස් නීතිය 1989දී බි්රතාන්යය සංශෝධනය කළා. එය වඩාත් ජන සම්මතවාදී ප්රමිතියකට ඔවුන් දැන් ගෙනැවිත් තිබෙනවා. අප තවමත් 1911 බි්රතාන්ය නීතියට සමාන වන නීතියක එල්බ ගෙන සිටීම ඛෙදජනකයි.’ නීතිඥ හා පර්යේෂිකා කිෂාලි පින්ටෝ ජයවර්ධන කියනවා.

තොරතුරු නීතිය ගැන මෑතදී පොතක් ලියා ඇති නීති පර්යේෂක ගිහාන් ගුණතිලක කියන්නේ හොඳ තොරතුරු නීතියක ගැබ් විය යුතු මූලධර්ම 9ක් තිබෙන බවයි. ඒවා සැකෙවින් මෙසේයි.

- රජයක් හැම විටම හැකි තාක් තොරතුරු හෙළි කිරීමට නැඹුරු විය යුතුයි (Maximum Disclosure). බදා ගෙන සිටිනවා වෙනුවට බෙදා ගැනීමට මුල් තැන දිය යුතුයි.

- යම් කෙනකු තොරතුරක් ඉල්ලන තුරු නොසිට, ස්වේච්ඡුාවෙන්ම මහජන තොරතුරු පළ කිරීම කළ යුතුයි (Obligation to Publish). මෙයට පරිපාලන මෙන්ම මූල්ය තොරතුරු හා වෙනත් දත්තද ඇතුළත් විය හැකියි. (තම වෙබ් අඩවි හරහා මෙසේ කරන රාජ්ය ආයතන ගණනාවක් තිබෙනවා.)

- මහජන ආයතන සියල්ලම විවෘත ආණ්ඩුකරණය ^Open Government& සංකල්පයට අනුගත විය යුතුයි. රහසිගතභාවය පෙරටු කොට ගත් පරිපාලන සම්ප්රදායන් ඉවත දමා විවෘත භාවය මුල් කර ගත් ක්රමවේදයන් හඳුන්වා දිය යුතුයි.

- නිශ්චිත හේතු නිසා මහජනයාට තොරතුරු දිය නොහැකි අවස්ථා හෙවත් ව්යතිරේක (Exceptions) හැකි තාක් සීමා කළ යුතුයි. එසේ නොදී සිටීමට පැහැදිලි සාධාරණීකරණයක් තිබිය යුතුයි.

- තොරතුරු අයිතිය ප්රායෝගිකව ක්රියාත්මක වීමට නිශ්චිත පරිපාලන ක්රමවේදයක් බිහි කළ යුතුයි. තොරතුරු සොයා එන මහජනයා රස්තියාදු නොකර කාර්යක්ෂමව හා ආචාරශීලීව තොරතුරු ලබාදෙන ක්රමයක් මේ නීතිය හරහා ස්ථාපිත විය යුතුයි. එසේම තොරතුරු සම්පාදනය කොට ලබාදීමට නීතියෙන් සීමිත කාලයක් නිශ්චය කළ යුතුයි. එසේම හරිහැටි ඉටු නොකෙරෙන තොරතුරු ඉල්ලීම් ගැන විමර්ශනය කළ හැකි ස්වාධීන ආයතනයක් පිහිටුවිය යුතුයි. (තොරතුරු කොමිසම නම් වන්නේ එයයි.)

- තොරතුරු ලබා ගැනීමේදී එයට යම් ගෙවීමක් කළ යුතු වුවත්, එම අය කිරීම සාධාරණ හා මහජනයාට දරා ගත හැකි එකක් විය යුතුයි. එහිදී මූලික සංකල්පය විය යුත්තේ තොරතුරුවලින් සන්නද්ධ වන ජන සමාජයේ වටිනාකම, එම තොරතුරු සම්පාදනය කිරීමට වැය වන මුදලට වඩා බෙහෙවින් වැඩි බවයි.

- සියලූ රාජ්ය ආයතනවල සියලූ රැස්වීම් මහජනතාවට විවෘත විය යුතුයි (Open Meetings). මන්ද තමන්ගේ නාමයෙන් නිලධාරීන් කුමක් කරන්නේද යන්න දැන ගැනීමට ජනතාවට අයිතියක් ඇති නිසා. ඉඳහිට ඇතැම් රැස්වීම් මහජනයාට විවෘත නොවුවත්, ඒවා පැවැත් වූ බව ප්රසිද්ධියේ ප්රකාශ කළ යුතුයි. සංවෘත රැස්වීම් පැවැත්වීම සාධාරණීකරණය කළ හැකි විය යුතුයි.

- තොරතුරු නීතිය සම්මත කර ගත් පසුව, රටේ පවතින අන් සියලූ නීති එයට අනුගත වන පරිදි නැවත විග්රහ කළ යුතුයි. ඉදිරියේදී සම්මත වන කිසිදු නීතියක් මගින් තොරතුරු හෙළි කිරීම සීමා නොකළ යුතුයි. එසේම යහ චේතනාවෙන් තොරතුරු මහජනයාට ලබා දෙන රාජ්ය නිලධාරීන්ට නිසි ආරක්ෂාව ලැබිය යුතුයි. නොබියව තම රාජකාරිය නීති ගරුකව කිරීමට රාජ්ය සේවකයන් සැමට හැකි වන පරිසරයක් තිබිය යුතුයි.

- රාජ්ය තන්ත්රයේ සේවය කිරීම නිසා තමන් අතට පත් වන, පොදු උන්නතියට වැදගත් තොරතුරු හෙළිදරවු කරන පුද්ගලයන්ට නීතිමය රැකවරණ ලැබිය යුතුයි (Protection for Whistle-blowers). රජයේ ආයතන තුළ කැරෙන අකටයුතුකම් ගැන තොරතුරු මාධ්යවලට හෝ වෙනත් පිරිසකට හෝ ලබා දීම අපරාධයක් හෝ විනය විරෝධී ක්රියාවක් ලෙස නොව පොදු උන්නතියට උදව් කිරීමක් ලෙස සැලකිය යුතුයි. එහිදී ආයතන සංග්රහයේ විධිවිධාන උල්ලංඝනය වුවත් එයට ඔබ්බට යන විනිශ්චයක් හරහා අදාළ තොරතුරු මුදා හරින පුද්ගලයන් එසේ කිරීමේ පොදු වැදගත්කම සැලකිල්ලට ගත යුතුයි.

තොරතුරු නීතිය පිළිබඳව නොවැම්බර් 17 වැනිදා කොළඹදී පැවති මහජන සංවාදයකදී මා කීවේ මෙයයි:

තොරතුරු අයිතිය දිනා ගැනීම දශක එක හමාරක පමණ සිවිල් ක්රියාකාරීත්වයේ මංසළකුණක්. එහෙත් නීතිය සම්මත කර ගත් පමණීන් අභියෝග හමාර වන්නේ නැහැ.

වඩාත් විවෘත වුත්, මහජනයාට වග වන්නා වුත් ආණ්ඩුකරණයකට දේශපාලකයන් හා රාජ්ය නිලධාරීන් සැවොම ආකල්පමය වශයෙන් ප්රවේශ විය යුතුයි.

තොරතුරු සොයා යන, තොරතුරු ලද විට ඒවා නිසි ලෙස විග්රහ කොට නිගමනවලට එළැඹීමේ හැකියාව හෙවත් තොරතුරු සාක්ෂරතාව (information literacy) සමාජයේ ප්රවර්ධනය කිරීම අප කාගේත් වගකීමක්.

ආවේග, අනුමාන, කුමන්ත්රණ තර්ක හෝ විශ්වාස මත පදනම් වනවා වෙනුවට දත්ත හා විග්රහයන් මත පදනම් වී නිගමනවලට එළඹීමටත්, ඒ හරහා අපේ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදය වඩාත් සවිබල ගැනීවීමටත් ලොකු වගකීමක් පුරවැසි හැමට තිබෙනවා.

See also:

15 October 2015: Exploring Open Data and Open Government in Sri Lanka

23 July 2015: සිවුමංසල කොලූගැටයා #227: භාෂණයේ නිදහසට හා ප්රශස්ත මාධ්යකරණයට දේශපාලන කැපවීමක් ඕනෑ!

21 Feb 2015: සිවුමංසල කොලූගැටයා #208: තොරතුරු අයිතිය තහවුරු කරන්නට තොරතුරු සාක්ෂරතාව අත්යවශ්යයි!

17 Feb 2015: සිවුමංසල කොලූගැටයා #207: “තොරතුරු නීතිය ලැබුණාට මදි. එයින් නිසි ඵල නෙළා ගත යුතුයි!”