This week’s Ravaya column (in Sinhala) is about a maverick scientist: Dr Yang Saing Koma. For 15 years, this Cambodian agronomist has driven a grassroots revolution that is changing farming and livelihoods in one of the least developed countries in Asia.

A champion of farmer-led innovation in sustainable agriculture, Koma founded the Cambodian Centre for Study and Development in Agriculture (CEDAC) in 1997. Today, it is the largest agricultural and rural development organisation in Cambodia, supporting 140,000 farmer families in 21 provinces.

He has just been honoured as one of this year’s six recipients of the Ramon Magsaysay Awards — the Asian Nobel Prize. I wrote about him in a recent English column too.

ලක් ගොවීන් රසායනික පොහොරට දැඩි සේ ඇබ්බැහි වීම ගැන ගිය සතියේ මා කළ විග්රහයට හොඳ ප්රතිචාර ලැබුණා. එ අතර කෘෂි විද්යා ක්ෂෙත්රය ද මනාව දත් පාඨකයකු කීවේ “ශ්රී ලංකාව වැනි කුඩා දුප්පත් රටවලට මෙබඳු ගෝලීය ප්රවණතාවලට එරෙහිවීමට අවශ්ය වුවත් ලෙහෙසියෙන් කළ නොහැකි බවයි”.

ඕනෑ ම ඇබ්බැහිකමකින් අත්මිදීම අසීරුයි. එහෙත් අපේ රට ඇතැම් දෙනා සිතන තරම් කුඩා හෝ “අසරණ” හෝ නොවන බව මා මීට පෙර මේ කොලමින් සාක්ෂි සහිතව පෙන්වා දී තිබෙනවා. ඕනෑකම හා අධිෂ්ඨානය ඇත්නම් අපේ අයාලේ ගිය කෘෂි ක්ෂෙත්රය නැවතත් යහපත් ප්රතිපත්ති හා පුරුදුවලට යොමු කර ගත හැකියි.

ගෝලීය පසුබිම තුළ අපේ රටේ “අසරණකම” ගැන අශූභවාදී තර්ක කරන අයට මා ගෙන හැර දක්වන්නේ අපටත් වඩා කුඩා, දුගී බවින් අධික ආසියානු රටවල් යහ අරමුණු සාර්ථක ලෙස ජය ගන්නා හැටියි. රසායනික පොහොර මත අධික ලෙස යැපීමේ හරිත විප්ලව සංකල්පයෙන් මෑතදී ඉවත් වූ කාම්බෝජයේ උදාහරණය මා අද මතු කරන්නට කැමතියි.

1958 සිට පිලිපීනයේ ස්වාධීන පදනමක් විසින් වාර්ෂිකව පිරිනමනු ලබන රේමන් මැග්සායිසායි ත්යාගය (Ramon Magsaysay Award) ආසියානු නොබෙල් ත්යාගය ලෙස හඳුන්වනවා. එය පිරිනමන්නේ සිය රටට, සමාජයට හා ලෝකයට සුවිශේෂී සේවයක් කරන අයටයි.

2012 මැග්සායිසායි ත්යාග අගෝස්තු 31 වනදා පිලිපීනයේ මැනිලා අගනුවරදී උත්සවාකාරයෙන් පිරිනමනු ලැබුවා. එහිදී මහජන සේවය සඳහා වන මැග්සායිසායි ත්යාගය කාම්බෝජයේ ආචාර්ය යැං සයිංග් කෝමාට (Dr. Yang Saing Koma) හිමි වුණා. සිය රටෙහි ගොවිතැන් කටයුතුවල නිහඬ විප්ලවයක් කරමින් සහල් නිෂ්පාදනය වැඩි කරන අතර ගොවීන්ගේ ජීවන තත්ත්වය හා ආත්ම අභිමානය දියුණු කිරීම ත්යාගයේ හේතු පාඨය ලෙස සඳහන් වුණා.

ආසියාවේ වඩාත් දුගී දුප්පත්කම වැඩි රටක් වන කාම්බෝජයේ ඒක පුද්ගල දළ දේශීය නිෂ්පාදිතය (GDP) ඩොලර් 930යි. එරට සමස්ත ආර්ථික නිෂ්පාදනයෙන් සියයට 33ක් ලැබෙන්නේ බෝග වගාවෙන් හා සත්ත්ව පාලනයෙන්. එරට මිලියන් 14ක ජනයාගෙන් තුනෙන් දෙකක් ජීවිකාව සපයා ගන්නේ් වී ගොවිතැනින්.

සිය රටේ ජීවන තත්ත්වය නඟා සිටුවීමට නම් වී ගොවිතැනින් පටන් ගත යුතු බව ජර්මන් සරසවියකින් ශෂ්ය විද්යාවේ ආචාර්ය උපාධියක් ලබා 1995දී සිය රට පැමිණි ආචාර්ය කෝමා මනා සේ වටහා ගත්තා. එහෙත් බටහිරින් උගෙන අපේ වැනි රටවලට ආපසු පැමිණ එ් දැනුම ගෙඩි පිටින් ආරෝපණය කරන උගතුන්වට වඩා කෝමා වෙනස් චරිතයක්.

ඔහුට ක්රමීය චින්තනයක් තිබෙනවා. ප්රශ්නවල මුල සොයා ගවේෂණය කිරීමත්, රෝග ලක්ෂණවලට මතුපිටින් ප්රතිකර්ම යොදනවා වෙනුවට රෝග නිධාන සොයා ප්රතිචාර දැක්වීමත් ඔහුගේ ක්රමවේදයයි.

ගොවීන්ගේ අවශ්යතාවන්ට කේන්ද්ර වූ ගොවිතැන් පිළිවෙත් මතු කර ගැනීම මුල පටන් ම කෝමාගේ ප්රමුඛතාවය වුණා. බොහෝ රටවල් කරන්නේ ජාතික අස්වනු ඉලක්ක සාදා ගෙන, එවා සාක්ෂාත් කරන්නට ගොවීන් ඉත්තන් සේ යොදා ගැනීමයි. එ මහා පරිමාණ ව්යාපෘතිවලදී, කෙටි කාලීන අධික අස්වනු ලැබීම සඳහා උවමනාවට වඩා කෘෂි රසායන ද්රව්ය යොදමින් කඩිනම් අරගලයක් කරනවා. දේශපාලන උද්යෝගපාඨ හා ජාතිකාභිමානී ප්රකාශ හමාර වූ පසු ණය බරිත වූ ගොවීන් ගැන නිලධාරීන් හෝ දේශපාලකයන් හෝ තකන්නේ නැහැ (අඩු තරමින් ඊළඟ මැතිවරණය එලඹෙන තුරු!)

මේ ක්රමයට වෙනස් වූ, කළබල නැති, ගොවි හිතකාමී හා පරිසර හිතකාමී ක්රමවේදයන් ප්රගුණ කරන්නට 1997දී කෝමා ගොවි කටයුතු අධ්යයන හා සංවර්ධනයට කැප වූ කාම්බෝජියානු කේන්ද්රය (Cambodian Centre for Study and Development in Agriculture, CEDAC) නම් රාජ්ය නොවන, ස්වෙච්චා සංවිධානය ඇරඹුවා. වසර 15ක් තුළ CEDAC ගොවි කටයුතු හා ග්රාම සංවර්ධනය පිළිබඳ කාමිබෝජයේ විශාලතම ජනතා සංවිධානය බවට පත් වී තිබෙනවා. අද ඔවුන් පළාත් 21ක ගොවි පවුල් 140,000ක් සමඟ ගනුදෙනු කරනවා. ගොවි තොරතුරු ජාල හරහා තවත් විශාල ගොවි ජනතාවක දැනුම වැඩි කරනවා.

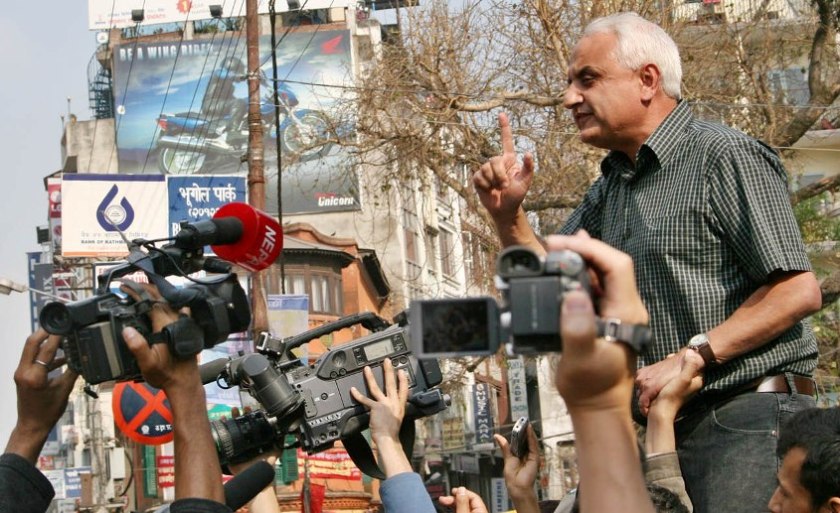

ආචාර්ය කෝමා අප සාමාන්යයෙන් සිතින් මවා ගන්නා ආකාරයේ (රැවුල වවා ගත්, උද්යොගපාඨ කියමින් මොර දෙන) විප්ලවවාදියකු නොවෙයි. ඔහු සිරුරින් කෙසග, සිහින් හඬින් කථා කරන, ඉතා ආචාරශීලී පුද්ගලයෙක්. එහෙත් මේ කුඩා මිනිසා චින්තන විප්ලවයක් හරහා කාම්බෝජ ගොවිතැන නව මගකට යොමු කර තිබෙනවා. උගත්කමේ මාන්නය පොඩියක්වත් නැති මේ අපුරු විද්යාඥයා ගොවීන්, කෘෂි පර්යේෂකයන්, රාජ්ය නිලධාරීන්, රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධාන ක්රියාකාරිකයන් මෙන් ම අදාළ පෞද්ගලික සමාගම් නියෝජිතයින් සමඟත් සාමූහිකව කටයුතු කරමින් පොදු උන්නතියට ක්රියා කරන අයෙක්.

කෝමා සහ CEDAC ආයතනයේ බලපෑම ඉතා හොඳින් කියා පාන උදාහරණය නම් වී වගාවේ SRI ක්රමය (System of Rice Intensification) කාම්බෝජයේ ව්යාප්ත කිරීමයි. දශකයක් තුළ වී ගොවීන් 100,000කට වැඩි දෙනෙකු SRI ක්රමයට නම්මවා ගන්නටත්, එ් හරහා එරට වී අස්වැන්න 60%කින් වැඩි කරන අතර රසායනික පොහොර හා දෙමහුම් වී ප්රභේද භාවිතය බොහෝ සෙයින් අඩු කිරීමටත් හැකි වී තිබෙනවා.

2002දී ටොන් මිලියන 3.82ක් වූ කාම්බෝජ වාර්ෂික වී නිෂ්පාදනය 2010 වන විට ටොන් මිලියන් 7.97 දක්වා ඉහළ ගියා. මේ වර්ධනයට සැලකිය යුතු දායකත්වයක් SRI ක්රමය හරහා ලැබුණු බව එරට රජය පිළි ගන්නවා. 2005දී කාම්බෝජය නිල වශයෙන් SRI ක්රමය එරට වී නිෂ්පාදන ක්රමෝපායක් බවට පත් කළා.

වී වගාවේ SRI ක්රමය මුලින් ම අත්හදා බලා හඳුන්වා දුන්නේ අප්රිකා මහද්වීපයට සමීප මැඩගස්කාරයේයි. 1980 ගණන්වල සුළුවෙන් ඇරඹි මේ ක්රමය මේ වන විට වී වගා කරන ඝර්ම කලාපයේ බොහෝ රටවල පැතිරී තිබෙනවා. SRI ක්රමය මෙරටට හඳුන්වා දී ඇතත් එතරම් ප්රචලිත වී නැහැ.

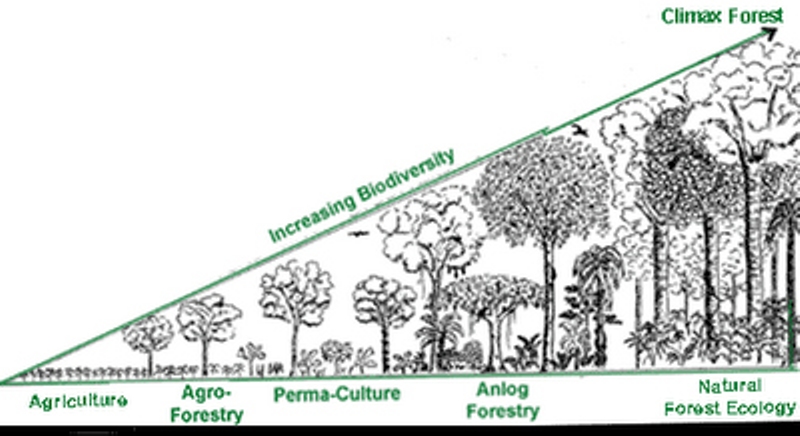

SRI ක්රමයේදී උත්සාහ කරන්නේ වඩාත් සකසුරුවම් ලෙසින් වාරි ජලය යොදා ගෙන වී වගා කිරීමට. සාම්ප්රදායිකව කුඹුරුවලට විශාල ජල ප්රමාණයක් යොමු කරනවා. 1990 ගණන්වලදී ආචාර්ය රේ විජේවර්ධන වරක් මට කීවේ වී කිලෝ එකක් නිපදවන්නට වාරි ජලය ටොන් 20ක් පමණ යොදන බවයි. මේ ජලයෙන් ඉතා වැඩි ප්රමාණයක් කරන්නේ වෙල් යායේ වල් පැළෑටි බිහි වීම වැළැක්වීම. වී ශාකය වර්ධනයට එතරම් ජලය කන්දරාවක් උවමනා නැහැ.

වල් පැළෑටි පාලනය සඳහා ජලය වෙනුවට තෙත කොළරොඩු (leaf mulch) යොදන SRI ක්රමයේදී කුඹුරුවල ජල අවශ්යතාවය බාගයකටත් වඩා අඩු කරනවා. ජල හිඟයට නිතර මුහුණ දෙන අද කාලේ මෙය විශාල සහනයක්.

SRI ක්රමයේ තවත් වෙනසක් නම් ඉතා ලාබාල (දින 10-12) වියේදී ගොයම් පැළ නිශ්චිත දුරකින් කුඹුරේ සිටුවීමයි. එමෙන් ම ගොයම් පැළ අතර (පසට නයිට්රජන් පොහොර තනා දීමේ ස්වභාවික හැකියාව ඇති) වෙනත් බෝග වවන්නට (inter-cropping) ගොවීන් උනන්දු කරවනවා. මෙබඳු පියවර කිහිපයක් හරහා අඩු ජලයක් හා අඩු රසායනික පොහොර යොදා වුවත් හොඳ අස්වැන්නක් ලද හැකියි.

1999දී SRI ක්රමය ගැන විදෙස් සඟරාවක ලිපියක් කියවූ ආචාර්ය කෝමා මුලින් එය තමන්ගේ වෙල් යායේ අත්හදා බැලූවා. ”මට උවමනා වුයේ මේ සංකල්ප කාම්බෝජයේ තත්ත්වයන්ට ගැලපෙනවා ද යන්න තහවුරු කර ගන්නයි. එය ප්රතිථල පෙන්වන විට මා අසල්වැසි ගොවි මහතුන් කැඳවා එය පෙන්නුවා. මුලින් ඔවුන් මේ ක්රමය විශ්වාස කළේ නැහැ. මා සතු සියළු දැනුම ඔවුන්ට දී මා කිව්වේ එය අත්හදා බලන්න කියායි”.

මෙසේ කුඩා පරිමාන වී ගොවීන් ටික දෙනෙකුගෙන් පටන් ගත් කාම්බෝජයේ SRI ක්රමය වසර කිහිපයක් තුළ රට පුරා ව්යාප්ත වී ගියා. එය ඉබේ සිදු වුයේ නැහැ. කෝමා හා CEDAC ආයතනය ආදර්ශක කෙත් යායන් පවත්වා ගෙන ගියා. රට පුරා සංචාරය කරමින් ගොවීන්ට ශිල්පක්රම කියා දුන්නා. ගොවි සඟරාවක්, රේඩියෝ හා ටෙලිවිෂන් මාධ්ය හරහා අත්දැකීම් බෙදා ගත්තා.

“මා හැම විට ම අපේ ගොවීන්ට කියන්නේ පොතේ උගතුන් වන අප කියන දේ එක විට පිළි ගන්නට එපා. ඔබ ම අත්හදා බලන්න. ඔබේ ගැටළු විසඳමින් වැඩි අස්වනු ලබා දෙන ක්රමවේදයක් පමණක් දිගට ම භාවිත කරන්න.”

කෝමා, ගොවීන්ගේ සහජ බුද්ධිය හා ප්රායෝගික දැනුම ඉතා ඉහළින් අගය කරන අසාමාන්ය ගණයේ උගතෙක්. “ගොවිතැන් කිරීම සම්බන්ධයෙන් ලෝකයේ සිටින ඉහළ ම විශේෂඥයන් වන්නේ කුඩා පරිමාණයේ ගොවියන් හා ගෙවිලියන්. විද්යාව ෙසෙද්ධාන්තිකව උගත් අප වැනි අය ගොවීන්ගෙන් ගුරුහරුකම් ලද යුතුයි! ඔවුන්ගෙන් උගනිමින්, ඔවුන් සමඟ ගොවිතැනේ ගැටළු විසඳීම කළ යුතුයි!”

කෝමා මෙසේ කියන විට මට සිහි වන්නේ ආචාර්ය රේ විජේවර්ධනගේ එ සමාන ආකල්පයන්. (2011 අගෝස්තු 21 හා 28 කොලම් බලන්න.) මූණ ඉච්ඡවට ගොවි රජා හා ගොවි මහතා ආදී යෙදුම් භාවිතා කළත් අපේ පොතේ උගතුන් හා පර්යේෂකයන් ගොවීන් ගැන දරණ ආකල්ප මා හොඳාකාර දැක තිබෙනවා. ලොව පුරා මේ පොත-කෙත අතර පරතරය තිබෙනවා.

කාම්බෝජයේ කෘෂිවිද්යා උපාධිධාරීන් ගොවි බිමට ගෙන ගොස් ඔවුන් සැබැවින් ම ගොවිතැනට යොමු කරන්නට කෝමා උත්සාහ කරනවා. SRI ක්රමයේ සාර්ථකත්වයෙන් පසු ඔහු තෝරා ගෙන ඇති ඊටත් වඩා භාර දුර අභියෝගය නම් එරට ගතානුගතික සරසවි හා වෘත්තීය අධ්යාපන ක්ෂෙත්රයේ දැක්ම පුළුල් කිරීමයි.

“මා හැම ගොවියකු ම දකින්නේ මනුෂ්යයකු හැටියටයි. ඔවුන්ට උපතින් ලද සහජ බුද්ධියත්, කුසලතාවයත් තිබෙනවා. එයට අමතරව අප බොහෝ දෙනාට නැති ප්රායෝගික අත්දැකීම් රැසක් තිබෙනවා. අප උත්සාහ කරන්නේ ගොවීන්ට ගෞරවාන්විතව සළකමින් ඔවුන් සමඟ සහයෝගයෙන් ගොවිතැන් කටයුතු වඩාත් ඵලදායී හා පරිසර හිතකාමී කරන්නටයි.” ඔහු කියනවා.

පරිසර හිතකාමී ගොවිතැනේදී අළුත් සංකල්ප හා ක්රමවේදයන් ගොවින් තුළින් ඉස්මතු කිරිමේ අරමුණින් ආසියාව හා අප්රිකාව පුරා කි්රයාත්මක වන PROLINNOVA නම් පර්යේෂණ ජාලයකට 2004 සිට CEDAC ආයතනය සම්බන්ධ වී සිටිනවා. මේ ජාලයේ දශකයක ක්රියාකාරකම් ගැන කෙටි වාර්තා චිත්රපට මාලාවක් 2010-11දී මා නිෂ්පාදනය කළා. එහි එක් කතාවක් සඳහා අප තෝරා ගත්තේ කාම්බෝජයේ ප්රති-හරිත විප්ලවයයි.

“ගොවියාට සවන් දෙන්න. ඔහුගේ මතයට ගරු කරන්න. සෙමින් සෙමින් පවත්නා තත්ත්වය වෙනස් කරන්න!” විනාඩි 40ක් පුරා ඔහු පටිගත කළ විඩියෝ සම්මුඛ සාකච්ඡව පුරා නැවත නැවතත් කීවේ මෙයයි. සාකච්ඡවේ ඉංග්රිසි පිටපත කියවන්න http://tiny.cc/KomaInt

විද්යා ගුරුකුලවාදයක් හෝ දේශපාලන මතවාදයක් හෝ කුමන්ත්රණ මානසිකත්වයක් නැති මේ දාර්ශනික කෘෂි විද්යාඥයාට අවශ්ය කාම්බෝජයේ ගොවීන්ගේ ජිවන මට්ටම නඟා සිටුවමින් එරට පරිසරය හා සොබා සම්පත් රැක ගැනීමයි. ඔවුන් දෙදෙනා කිසි දිනෙක මුණ නොගැසුනත්, කාම්බෝජයේ රේ විජේවර්ධන හැටියට යං සයින් කෝමා මා දකින්නේ එ නිසයි.

කෙටි වාර්තා චිත්රපට නරඹන්න: http://tiny.cc/ProFilms