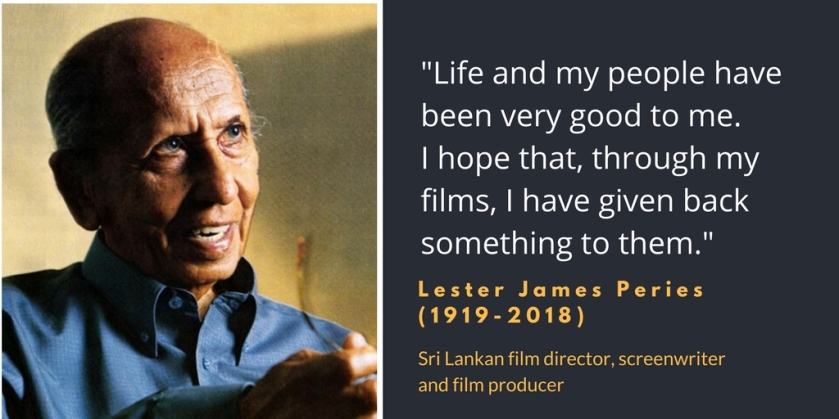

In my Ravaya column published in the printed edition of 6 May 2018, I look back at the long and illustrious career of Sri Lanka’s grand old man of the cinema, Lester James Peries (1919-2018) who died last week. As others assess his major contributions to the Sinhala cinema and in evolving an Asian cinema, I focus on his role as a public intellectual — one who wrote widely on matters of culture and society.

ලෙස්ටර් ජේම්ස් පීරිස් (1919-2018) සූරීන් රටත් ලෝකයත් හඳුනා ගත්තේ ආසියානු සිනමාවේ දැවැන්තයකු ලෙසයි. ඔහු ගැන කැරෙන ආවර්ජනා හා ප්රණාමයන් බොහෝමයක් හුවා දක්වන්නේත් එයයි.

එහි කිසිදු වරදක් නැතත්, ලෙස්ටර් සිනමාකරුවකු පමණක් නොවෙයි. පත්ර කලාවේදියකු ලෙස වෘත්තීය ජීවිතය ඇරැඹූ ඔහු ජීවිත කාලය පුරා ඔහුගේ මවු බස වූ ඉංග්රීසියෙන් ලේඛන කලාවේ යෙදුණා. ඔහුගේ සියුම් වූත් සංවේදී වූත් චින්තනය මේ ලේඛන තුළින් ද මැනවින් මතු වනවා.

ඉංග්රීසි බස ව්යක්ත ලෙසත්, හුරුබුහුටි ලෙසත් හැසිරවීමේ සමතකු වූ ඔහු පොදු උන්නතියට කැප වූ බුද්ධිමතකු (public intellectual) ලෙසත් අප සිහිපත් කළ යුතු බව මා සිතනවා. අද තීරු ලිපිය වෙන් වන්නේ ලෙස්ටර්ගේ මේ භූමිකා මදක් විමසා බලන්නයි.

2005දී ආසියානු සිනමා කේන්ද්රය ප්රකාශයට පත් කළ ‘ලෙස්ටර් ජේම්ස් පීරිස් – දිවිගමන හා නිර්මාණ’ (Lester James Peries: Life and Works) නම් ඉංග්රීසි පොතෙහි ලෙස්ටර්ගේ ජීවිතයේ මේ පැතිකඩ ගැන බොහෝ තොරතුරු අඩංගුයි.

එය රචනා කළේ සිනමාවටත්, කලා ක්ෂේත්රයටත් සමීපව සිටි මහාචාර්ය ඒ. ජේ. ගුණවර්ධනයි (1932 – 1998). එහෙත් අත්පිටපත පරිපූර්ණ කිරීමට පෙර ඔහු අකාලයේ මිය ගිය පසු එම කාරියට අත ගැසුවේ ඇෂ්ලි රත්නවිභූෂණ හා රොබට් කෲස් දෙදෙනායි.

මේ පොතට ලෙස්ටර් ගැන ශාස්ත්රීය ඇගැයීමක් ලියා තිබෙන්නේ සන්නිවේදන මහාචාර්ය විමල් දිසානායකයි. ලෙස්ටර් සිනමාවෙන් කළ හපන්කම් තක්සේරු කරන අතරම ඔහුගේ සමාජ විඥානය, සාංස්කෘතික චින්තනය හා පොදු අවකාශයේ දශක ගණනක් සැරිසැරූ බුද්ධිමතකු ලෙස කළ දායකත්වය ගැනත් එයින් විවරණය කැරෙනවා.

”පොදු උන්නතියට කැප වූ බුද්ධිමතකු ලෙස ලෙස්ටර්, පුවත්පත් ලිපි, රේඩියෝ සාකච්ඡා හා සජීව මහජන සංවාද හරහා සිනමාව, කලාව හා සංස්කෘතික තේමා ගැන නිතර සිය අදහස් ප්රකාශක කළා. වාරණය කලාවට කරන අහිතකර බලපෑම්, සිනමා සංරක්ෂණාගාරයක අවශ්යතාව හා ළමා සිනමා ධාරාවක් බිහි කිරීමේ වැදගත්කම ආදී විවිධ මතෘකා ගැන විවෘතව පෙනී සිටියා” යයි මහාචාර්ය දිසානායක කියනවා.

තවත් තැනෙක මහාචාර්ය විමල් දිසානායක මෙසේ ලියා තිබෙනවා. ”සිනමාකරුවකු ලෙස සිය නිර්මාණ හරහා ලෙස්ටර් තත්කාලීන සමාජ ප්රශ්නවලට ඇති තරම් අවධානය යොමු නොකළා යයි සමහරුන් කියනවා. එහෙත් එය නිවැරැදි හෝ සාධාරණ නැහැ. සිනමා අධ්යක්ෂවරයකු ලෙස ලෙස්ටර්ගේ මූලික තේමාව වී ඇත්තේ ලක් සමජයේ මධ්යම පාන්තිකයන්ගේ නැගීම හා පිරිහීම ගැනයි. මධ්යම පන්තියේ පවුල් ජීවිත අරගලයන්ට පසුබිම් වන සමාජ, ආර්ථීක හා මනෝ විද්යාත්මක පසුබිම ඔහු මැනවින් ග්රහනය කරනවා. ඒ හරහා රටේ සිදු වෙමින් පවතින සමාජයීය හා සාංස්කෘතික පරිනාමයන් ඔහු විචාරයට ලක් කරනවා. මෑත කාලීන සමාජයේ සෙමින් නමුත් සැබැවින්ම සිදු වන විපර්යාස ගැන ඔහුගේ සිනමා නිර්මාණවල යටි පෙලෙහි බොහෝ නිරීක්ෂණ තිබෙනවා.”

සිය චිත්රපටවල දේශපාලන හා සමාජ විචාරය සියුම්ව මතු කළ ලෙස්ටර්, පුවත්පත් ලිපි, විද්වත් සංවාද ආදියෙහි ඊට වඩා ඍජුව සමාජ ප්රශ්න විග්රහ කළා. එහිදීත් ඔහුගේ බස හැසිරවීම සරලයි. උපාහසය හා හාස්යය මුසු කළ ශෛලියක් ඔහුට තිබුණා.

උදාහරණයකට ඔහු වරක් කළ මේ ප්රකාශය සලකා බලන්න: ”1956දී රේඛාව චිත්රපටය ප්රදර්ශනය කිරීමට කලින් සිංහල චිත්රපට 42ක් නිපදවා තිබූණා. එහෙත් ඒ එකක්වත් සැබැවින්ම සිංහල වූයේත් නැහැ. හරිහමන් චිත්රපට වූයේත් නැහැ. ඇත්තටම ‘සිංහල සිනමාව’ 1947දී ලැබුවේ වැරැදි ආරම්භයක් (false start).”

දකුණු ඉන්දියානු චිත්රපට ගෙඩි පිටින් අනුකරණය කරමින්, මුළුමනින්ම චිත්රාගාර තුළ රූපගත කොට නිර්මාණය කෙරුණු එම චිත්රපට ගැන කිව යුතු සියල්ල මේ කෙටි විග්රහයෙහි ගැබ් වී තිබෙනවා!

මෙරට ජාතික මට්ටමේ සිනමා සංරක්ෂණාගාරයක අවශ්යතාව ගැන ලෙස්ටර් මුලින්ම කතා කළේ 1957දී. එය ඔහු ජීවිත කාලය පුරා යළි යළිත් අවධාරණය කළත් තවමත් බිහි වී නැහැ. ලෙස්ටර්ට ප්රනාම පුද කරන සියලුම දේශපාලකයන් බලයේ සිටිද්දී ඒ පිළිබඳ සිය වගකීම් පැහැර හැරියා.

වාණිජ සිනමාව හා කලාත්මක සිනමාව යන ධාරා දෙකෙහි යම් සමබරතාවක් පවත්වා ගැනීමේ වැදගත්කමද ලෙස්ටර් නිතර මතු කළ අවශ්යතාවක්. වෙළඳෙපොළ ප්රවාහයන් වාණිජ සිනමාව නඩත්තු කළත් කලාත්මක සිනමාවට රාජ්ය හා දානපති අනුග්රහය ලැබිය යුතු බව ඔහු පෙන්වා දුන්නා.

1977දී පැවැති සම්මන්ත්රණයක කතා කරමින් ලෙස්ටර් කළ ප්රකාශයක් මහාචාර්ය විමල් දිසානායක උපුටා දක්වනවා: ”සිංහල සිනමාවට වසර 30ක් ගත වීත්, කලාත්මක සිනමා නිර්මාණ සඳහා කිසිදු දිරි ගැන්වීමක් ලැබී නැහැ. මේ තාක් දේශීය වූත් කලාත්මක වූත් සිනමා නිර්මාණ සිදු කර ඇත්තේ සිනමා මාධ්යයට මුළු හදවතින්ම කැප වූ හුදෙකලා සිනමාකරුවන් විසින් පමණයි. කලාත්මක චිත්රපට අධ්යක්ෂනය කරන තරුණ සිනමාවේදීන් එසේ කරන්නේ අසීමිත බාධක හා අභියෝග රැසක් මැදයි. බොහෝ විට ඔවුන්ට ඉතිරි වන්නේ සිනමා විචාරකයන් ටික දෙනකුගේ ප්රශංසා පමණයි. ඉනික්බිති ඊළඟ නිර්මාණය කරන්නට වසර ගණනාවක් ගත වනවා. එකී කාලය තුළ ඔවුන් දිවි රැක ගන්නේ කෙසේද යන්න ගැන රාජ්යය හෝ සමාජය සොයා බලන්නේ නැහැ. අපේ යයි කිව හැකි සිනමා සම්ප්රදායක් පියවරෙන් පියවර හෝ බිහි වන්නේ මේ ධෛර්යවන්ත, හුදෙකලා සිනමාකරුවන් කිහිප දෙනා අතින්.”

ඇත්තටම මේ විසම යථාර්ථය සිනමා දැවැන්තයකු වූ ලෙස්ටර්ටත් බලපෑවා. 1957 – 2006 වකවානුවේ වසර 50ක කාලයක් තුළ ඔහු නිර්මාණය කළේ වෘතාන්ත චිත්රපට 20ක් පමණයි. එක් චිත්රපටයක් හමාර කර ඊළඟ නිර්මාණය සඳහා මුදල් සොයා ගන්නට වසර ගණන් බලා සිටීමට සිදු වුණා.

එහෙත් ඔහු ඒ ගැන රජයන්ට හෝ සමාජයට දොස් කියමින්, හූල්ලමින් කාලය ගත කළේ නෑ. අභියෝග හා අභිනන්දන දෙකම උපේක්ෂාවෙන් බාර ගත්තා.

2002දී ඉන්දියානු සිනමාකරු බික්රම් සිං (Bikram Singh) අධ්යක්ෂණය කළ ‘පීරිස්ගේ ලෝකය’ (The World of Peries) නම් වාර්තා චිත්රපටයේ අවසානයේ ලෙස්ටර් මෙසේ කියනවා:

”මා අඩ සියවසක් පමණ කාලයක් තිස්සේ චිත්රපට හැදුවා. එය හරියට දිගු කාලීන වන්දනා ගමනක් වගේ. නමුත් මා සළකන හැටියට මගේ ජීවිතය සාර්ථකයි. මගේ සහෝදර ජනයා මට මහත් ආදරයෙන් සලකනවා. මගේ චිත්රපට හරහා මා ඔවුන්ට (හරවත්) යමක් ලබාදී ඇතැයි මා සිතනවා.”

2000දී ජනාධිපති චිත්රපට සම්මාන උළෙලේදී කතා කරමින් ලෙස්ටර් සිය ක්ෂේත්රය විග්රහ කළේ මෙහෙමයි: ”සිනමාව කියන්නේ කලාවක්, කර්මාන්තයක් වගේම ව්යාපාරයක්. මේ සාධක තුන තුලනය කර ගැනීම කිසිදු රටක ලෙහෙසි පහසු කාර්යයක් නොවෙයි. අපේ ලාංකික සිනමාවේ අර්බුදයට එක් ප්රධාන හේතුවක් වන්නේ ද මේ තුලනය සොයා ගත නොහැකි වීමයි.

”එහෙත් මා තවමත් බලාපොරොත්තු අත්හැර නැහැ. මගේ මුළු ජීවිතයම කේන්ද්ර වූයේ සිනමාව වටායි. 1952දී මා බ්රිතාන්යයේ සිට යළිත් මවු රටට පැමිණ සිනමාකරුවකු නොවූවා නම්, මා සදාකාලිකව පිටුවහලකු (exile) වී සිටින්නට තිබුණා. මගේ අනන්යතාව මා සොයා ගත්තේ මෙරටට පැමිණ චිත්රපට නිර්මාණය කිරීමෙන්. මේ රටේ තිබෙන අපමණක් ප්රශ්න හා අභියෝග මැද වුණත් මගේ රටේම යළිත් උපදින්නට මා තවමත් කැමතියි. ශ්රී ලංකාව වැනි රටක් තවත් නැහැ.”

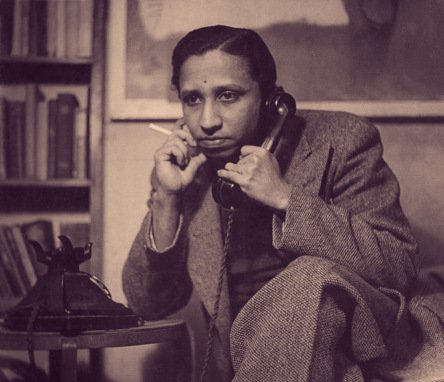

ලෙස්ටර් එහිදී සිහිපත් කළේ ඔහුගේ ජීවිතයේ මුල් අවදියයි. පාසල් අධ්යාපනය හමාර කළ ඔහු වයස 20දී (1939) ‘ටයිම්ස් ඔෆ් සිලෝන්’ පත්රයේ කර්තෘ මණ්ඩලයට බැඳුණා. එවකට එහි කතුවරයා වූයේ ප්රකට ඉන්දියානු පත්ර කලාවේදී ෆ්රෑන්ක් මොරායස්.

වසර කිහිපයක්ම ලෙස්ටර් ටයිම්ස් පත්රයට කලා ක්ෂේත්රයේ ලිපි සම්පාදනය කළා. මේ අතරවාරයේ ඔහු නාට්ය කණ්ඩායම්වලටදල රේඩියෝවටද සම්බන්ධ වුණා.

ප්රකට චිත්ර ශිල්පියකු වූ අයිවන් පීරිස් (1921-1988) ලෙස්ටර්ගේ බාල සොහොයුරා. අයිවන් කලා ශිෂ්යත්වයක් ලැබ ලන්ඩන් නුවරට ගියේ 1947දී. ඒ සමඟ ලෙස්ටර් ද එහි ගියා.

ලන්ඩන් නුවර ‘ටයිම්ස් ඔෆ් සිලෝන්’ කාර්යාලයේ සේවය කරමින් බ්රිතාන්ය කලා ක්ෂේත්රය පිළිබඳ සතිපතා වාර්තා මෙරට පත්රයට ලියා එවූ ඔහු කෙටි චිත්රපට අධ්යක්ෂණයට යොමු වූයේ එහිදීයි.

ලෙස්ටර් අධ්යක්ෂනය කළ කෙටි චිත්රපටයක් නරඹා පැහැදීමට පත්ව සිටි බ්රිතාන්ය වාර්තා චිත්රපට අධ්යක්ෂ රැල්ෆ් කීන් (1902-1963) පසුව ශ්රී ලංකාවේ රජයේ චිත්රපට අංශයට බැදුණා. ලෙස්ටර් යළිත් මවු රටට ගෙන්වා ගැනීමට මූලික වූයේ ඔහුයි.

1952-55 වකවනුවේ ලෙස්ටර් රජයේ චිත්රපට අංශයේ වාර්තා චිත්රපට කිහිපයක් නිර්මාණය කිරීමට මුල් වුණා. එහෙත් නිලධාරිවාදය සමග පොරබැදීමෙන් හෙම්බත් වූ ඔහු, ටයිටස් ද සිල්වා (පසුව ටයිටස් තොටවත්ත) සමග එයින් ඉවත් වුණා.

එයින් පසු ඔවුන් රේඛාව චිත්රපටය (1956) නිපදවීමට සම්බන්ධ වූ සැටිත් එයින් මෙරට දේශීය සිනමාව නව මඟකට යොමු වූ සැටිත් අප දන්නවා.

කියැවීමෙන්, සංචාරයෙන් හා සමාජ අත්දැකීමෙන් බහුශ්රැත වූවත්, ලෙස්ටර් උගතකු ලෙස කිසි විටෙක පෙනී සිටියේ නැහැ. 1985දී කොළඹ සරසවියෙනුත්, 2003දී පේරාදෙණිය සරසවියෙනුත් ඔහුට ගෞරව ආචාර්ය උපාධි පිරිනැමුණා.

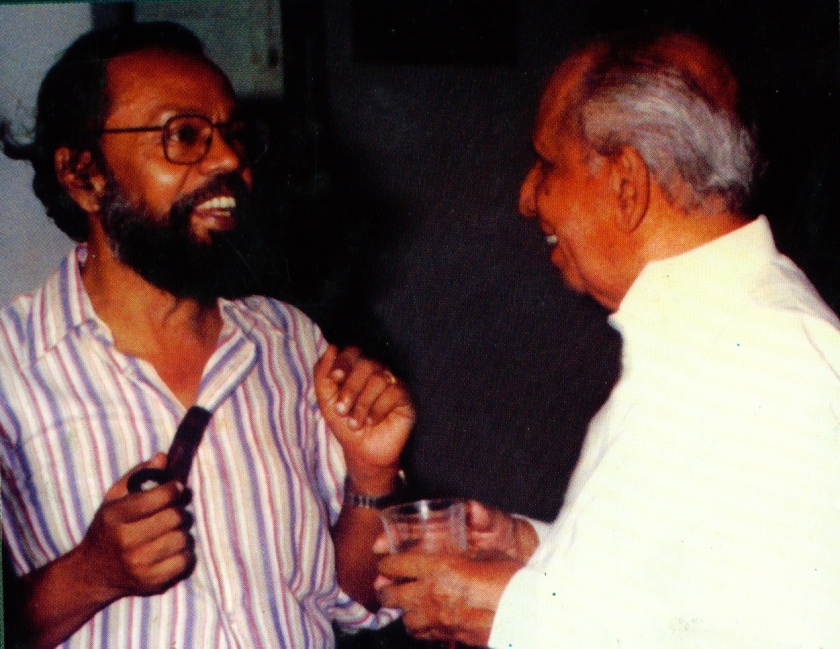

ඔහුගේ සමීපතයන් ඔහු දැන සිටියේ හාස්යයට ලැදි, ඉතා විනීත ගතිපැවතුම් සහිත එහෙත් දඟකාර මනසක් තිබූ අයෙක් ලෙසයි.

2003 (එනම් වයස 84දී) ගෞරව උපාධිය පිළිගනිමින් පේරාදෙණිය සරසවි උපාධි ප්රධානෝත්සවය අමතා කළ කථාවේදී ඔහු මෙසේ ද කීවා: ”සිනමා කර්මාන්තයේ තාක්ෂණය කෙමෙන් ඉදිරියට යනවා. එහෙත් චිත්රපට නිර්මාණය යනු හුදෙක් යන්ත්ර හා උපාංග සමග කරන හරඹයක් නොවෙයි. කෙතරම් දියුණු උපකරණ හා පහසුකම් තිබුණත් නිර්මාණශීලීත්වය නැතිනම් හොඳ චිත්රපට හදන්න බැහැ. එසේම නිර්මාණශීලීත්වය පමණක් සෑහෙන්නේත් නැහැ. මනුෂ්යත්වයට ගරු කරන, කතාවේ චරිත පිළිබඳව සානුකම්පිත වන, තමන් පිළිබිඹු කරන සමාජය හා එහි ජනයා ගැන ආදරයක් තිබෙන ජීවන දර්ශනයක් ද හොඳ සිනමාකරුවකුට අවශ්යයි. මේ ගුණාංගවලින් තොරව කෙතරම් තාක්ෂණිකව ඉහළ චිත්රපට හැදුවත් ඒවායේ හිස් බවක්, විකෘතියක් හෝ ජීවිතයට එරෙහි වීමක් හමු වේවි.”

”වසර 53ක් චිත්රපට හැදුවාට පසු මා නොදන්නේ මොනවාදැයි දැන් මා දන්නවා. එහෙත් මා දන්නේ මොනවාද යන්න නම් තවමත් මට පැහැදිලි නැහැ!”

(ලෙස්ටර්ගේ උධෘත සියල්ල මවිසින් අනුවාදය කර මේ ලිපියේ භාවිත කොට තිබෙනවා.)