Text of my column written for Echelon monthly business magazine, Sri Lanka, June 2015 issue

Sri Lanka: Unclear on Nuclear

By Nalaka Gunawardene

Should Sri Lanka consider nuclear energy for its medium to meet its long term electricity generation needs?

This has been debated for years in scientific and policy circles. It has come into sharp focus again after Sri Lanka signed a bilateral agreement with India “to cooperate in peaceful uses of nuclear energy”.

Under the agreement, signed in New Delhi on 16 February 2015 during President Maithripala Sirisena’s first overseas visit, India will help Sri Lanka build its nuclear energy infrastructure, upgrade existing nuclear technologies and train specialised staff. The two countries will also collaborate in producing and using radioactive isotopes.

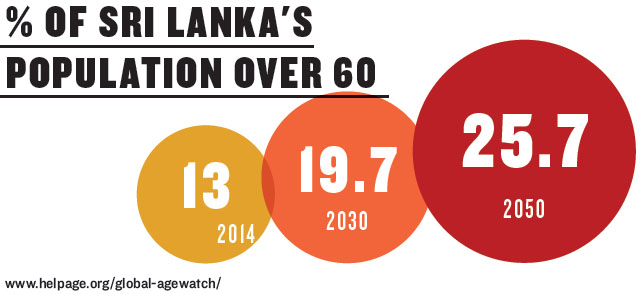

On the same day, a story filed from the Indian capital by the Reuters news agency said, “India could also sell light small-scale nuclear reactors to Sri Lanka which wants to establish 600 megawatts of nuclear capacity by 2030”.

This was neither confirmed nor denied by officials. The full text has not been made public, but a summary appeared on the website of Sri Lanka’s Atomic Energy Board. In it, AEB reassured the public that the deal does not allow India to “unload any radioactive wastes” in Sri Lanka, and that all joint activities will comply with standards and guidelines set by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), a UN body in which both governments are members.

According to AEB, Sri Lanka has also signed a memorandum of understanding on nuclear cooperation with Russia, while another is being worked out with Pakistan.

Beyond such generalities, no specific plans have been disclosed. We need more clarity, transparency and adequate public debate on such a vital issue with many economic, health and environmental implications. Yaha-paalanaya (good governance) demands nothing less.

South Asia’s nuclear plans

The South Asian precedent is not encouraging. Our neighbouring countries with more advanced in nuclear programmes have long practised a high level of opacity and secrecy.

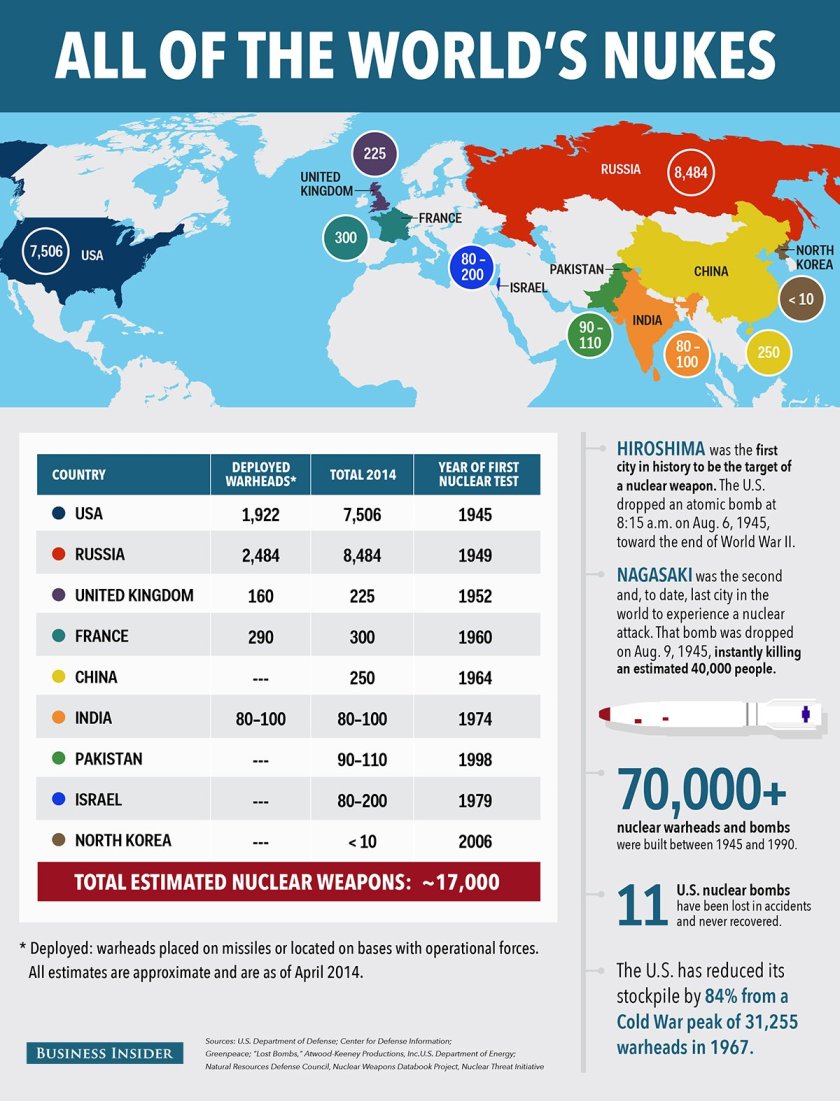

Two countries — India and Pakistan – already have functional nuclear power plants, which generate around 4% of electricity in each country. Both have ambitious expansion plans involving global leaders in the field like China, France, Russia and the United States. Bangladesh will soon join the nuclear club: it is building two Russian-supplied nuclear power reactors, the first of which will be operational by 2020.

India and Pakistan also possess home-built nuclear weapons, and have refused to sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Specifics of their arsenals remain unknown.

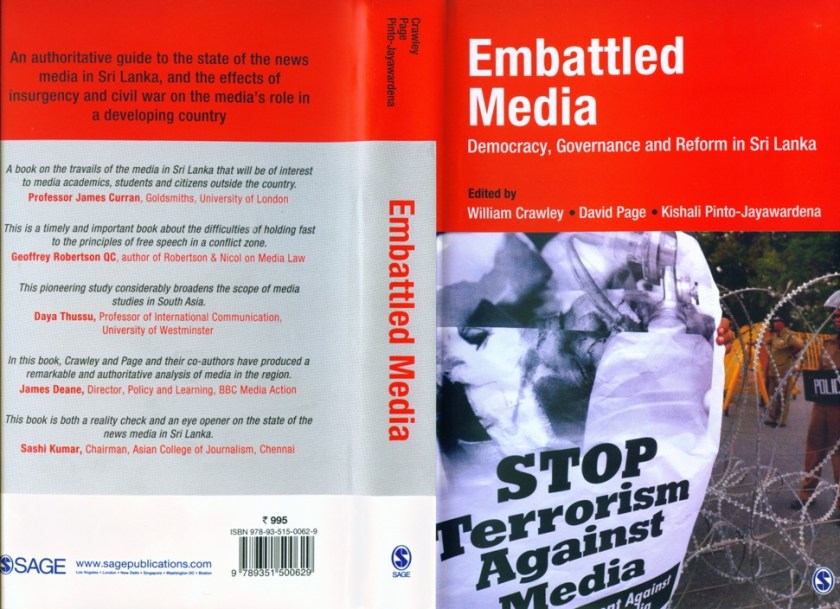

Both countries have historically treated their civilian and military nuclear establishments as ‘sacred cows’ beyond any public scrutiny. India’s Official Secrets Act of 1923 covers its nuclear energy programme which cannot be questioned by the public or media. Even senior Parliamentarians complain about the lack of specific information.

It is the same, if not worse, in Pakistan. Pakistani nuclear physicist Dr Pervez Hoodbhoy, an analyst on science and security, finds this unacceptable. “Our nuclear power programme is opaque since it was earlier connected to the weapons programme. Under secrecy, citizens have much essential information hidden from them both in terms of safety and costs.”

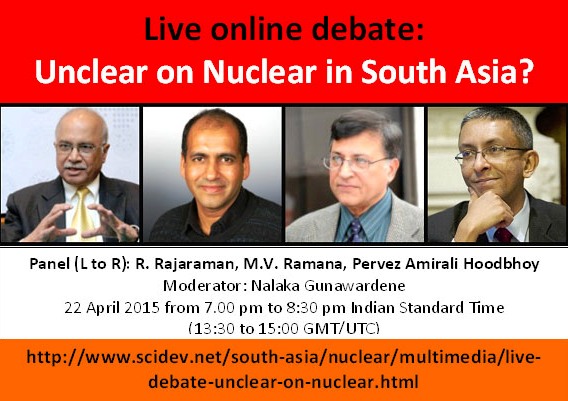

Safety of nuclear energy dominates the agenda more than four years after Japan’s Fukushima nuclear accident of March 2011. The memories of Chernobyl (April 1986) still linger. These concerns were flagged in a recent online debate on South Asia’s critical nuclear issues that I moderated for SciDev.Net. With five panellists drawn from across the opinion spectrum, the debate highlighted just how polarised positions are when it comes to anything nuclear in our part of the world.

Bottomline

The bottomline: all South Asian countries need more electricity as their economies grow. Evidence suggests that increasing electricity consumption per capita enhance socio-economic development.

The World Bank says South Asia has around 500 million people living without electricity (most of them in India). Many who are connected to national grids have partial and uneven supply due to frequent power outages or scheduled power cuts.

The challenge is how to generate sufficient electricity, and fast enough, without high costs or high risks? What is the optimum mix of options: should nuclear be considered alongside hydro, thermal, solar and other sources?

In 2013, Sri Lanka’s total installed electricity generation capacity in the grid was 3,290 MegaWatts (MW). The system generated a total electricity volume of 12,019.6 GigWatt-hours (GWh) that year. The relative proportions contributed by hydro, thermal and new renewable energies (wind, solar and biomass) vary from year to year. (Details at: http://www.info.energy.gov.lk/)

In a year of good rainfall, (such as 2013), half of the electricity can still come from hydro – the cheapest kind to generate. But rainfall is unpredictable, and in any case, our hydro potential is almost fully tapped. For some years now, it is imported oil and coal that account for a lion’s share of our electricity. Their costs depend on international market prices and the USD/LKR exchange rate.

Should Sri Lanka phase in nuclear power at some point in the next two decades to meet demand that keeps rising with lifestyles and aspirations? Much more debate is needed before such a decision.

Nuclear isn’t a panacea. In 2003, a study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on the future of nuclear power traced the “limited prospects for nuclear power” to four unresolved problems, i.e. costs, safety, waste and proliferation (http://web.mit.edu/nuclearpower/).

A dozen years on, the nuclear industry is in slow decline in most parts of the world says Dr M V Ramana, a physicist with the Program on Science and Global Security at Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. “In 1996, nuclear power contributed about 17.6% to the world’s electricity. By 2013, it was been reduced to a little over 10%. A large factor in this decline has been the fact that it was unable to compete economically with other sources of power generation.”

Safety issues

Beyond capital and recurrent cost considerations, issues of public safety and operator liability dominate the nuclear debate.

Take, for example, Pakistan’s recent decision to install two Chinese-supplied 1,100 MW reactors near Karachi, a megacity that packs almost Sri Lanka’s population. When concerned citizens challenged this in court, the government pleaded “national security was at stake” and so the public could not be involved in the process.

Dr Hoodbhoy is unconvinced, and cautions that his country is treading on very dangerous ground. He worries about what can go wrong – including reactor design problems, terrorist attacks, and the poor safety culture in South Asia that can lead to operator error.

He says: “The reactors to be built in Karachi are a Chinese design that has not yet been built or tested anywhere, not even in China. They are to be sited in a city of 20 million which is also the world’s fastest growing and most chaotic megalopolis. Evacuating Karachi in the event of a Fukushima or Chernobyl-like disaster is inconceivable!”

Princeton’s Dr Ramana, who has researched about opacity of India’s nuclear programmes, found similar aloofness. “The claim about national security is a way to close off democratic debate rather than a serious expression of some concern. It should be the responsibility of authorities to explain exactly in what way national security is affected.”

See also: India’s Nuclear Enclave and Practice of Secrecy. By M V Ramana. Chapter in ‘South Asian Cultures of the Bomb’ (Itty Abraham, ed., Indiana University Press, 2009)

Nuclear Dilemmas

Putting the nuclear ‘genie’ back in the bottle may not be realistic. The World Nuclear Association, an industry network, says there were 435 commercial nuclear power reactors operating in 31 countries by end 2014. Another 70 are under construction.

Following Fukushima, public apprehensions on the safety of nuclear power plants have been heightened. Governments – at least in democracies – need to be sensitive to public protests while seeking to ensure long term energy security.

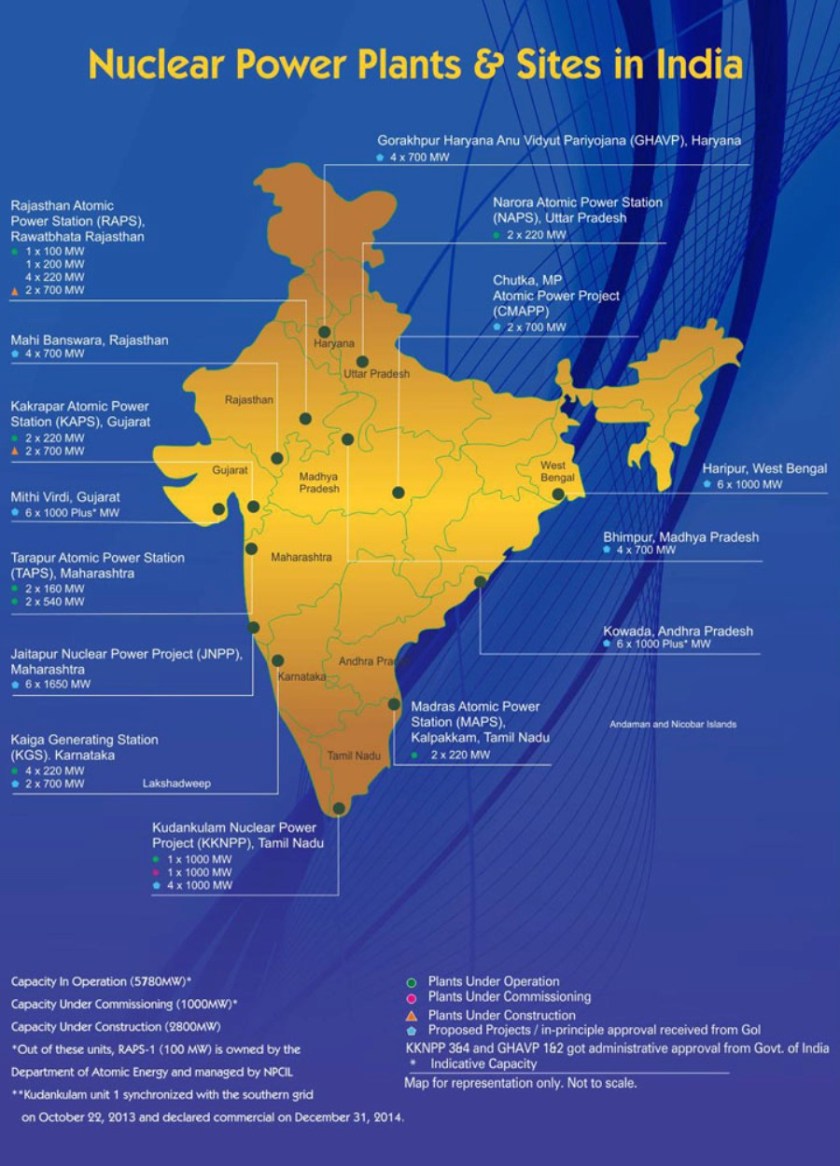

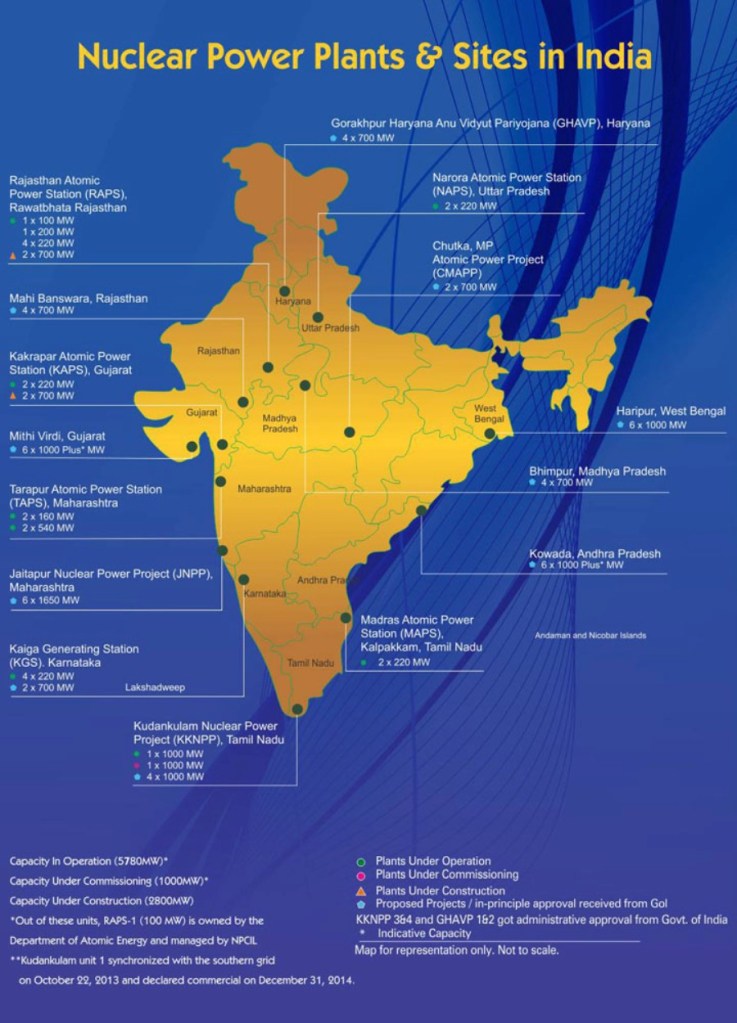

By end 2014, India had 21 nuclear reactors in operation in 7 nuclear power plants, with a total installed capacity of 5,780 MW. Plans to build more have elicited sustained protests from local residents in proposed sites, as well as from national level advocacy groups.

For example, the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant in Tamil Nadu, southern India — which started supplying to the national power grid in mid 2013 — has drawn protests for several years. Local people are worried about radiation safety in the event of an accident – a concern shared by Sri Lanka, which at its closest (Kalpitiya) is only 225 km away.

India’s Nuclear Liability Law of 2010 covers both domestic and trans-boundary concerns. But the anti-nuclear groups are sceptical. Praful Bidwai, one of India’s leading anti-nuclear activists, says the protests have tested his country’s democracy. He has been vocal about the violent police response to protestors.

Meanwhile, advocates of a non-nuclear future for the region say future energy needs can be met by advances in solar and wind technologies as well as improved storage systems (batteries). India is active on this front as well: it wants to develop a solar capacity of 100,000 MW by 2022.

India’s thrust in renewables does not affect its nuclear plans. However, even pro-nuclear experts recognise the need for better governance. Dr R Rajaraman, an emeritus professor of physics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, wants India to retain the nuclear option — but with more transparency and accountability.

He said during our online debate: “We do need energy in India from every possible source. Nuclear energy, from all that I know, is one good source. Safety considerations are vital — but not enough to throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

Rajaraman argued that nuclear energy’s dangers need to be compared with the hazards faced by those without electricity – a development dilemma. He also urged for debate between those who promote and oppose nuclear energy, which is currently lacking.

Any discussion on nuclear energy is bound to generate more heat than light. Yet openness and evidence based discussion are essential for South Asian countries to decide whether and how nuclear power should figure in their energy mix.

In this, Sri Lanka must do better than its neighbours.

Full online debate archived at: http://www.scidev.net/south-asia/nuclear/multimedia/live-debate-unclear-on-nuclear.html

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene is on Twitter @NalakaG and blogs at http://nalakagunawardene.com.