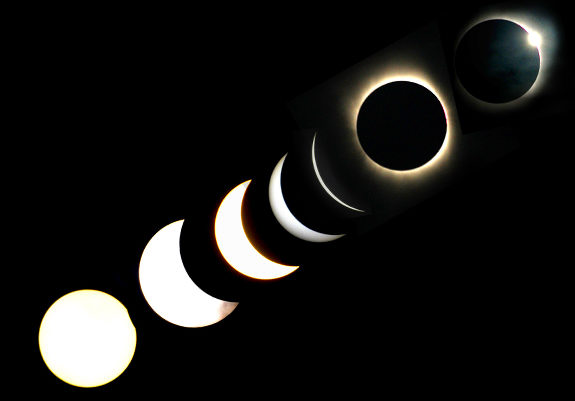

This century’s longest solar eclipsed moved across Asia on 22 July 2009, wowing scientists and the public alike. Asia’s multifarious media covered the solar eclipse with great enthusiasm and from myriad locations across the vast continent.

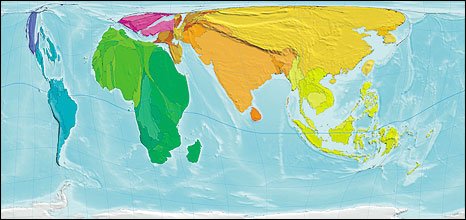

The path of the eclipse’s totality –- where the sun was completely obscured by the Moon for a few astounding minutes –- started in northern India. It then crossed through Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar and China, before heading out to the Pacific Ocean. Those who were lucky enough to be at the right place at the right time saw one of Nature’s most spectacular phenomena. It was certainly a sight to behold, capture on film, and cherish for a lifetime.

But many along the path missed this chance as clouds obscured the Sun. It’s the rainy season in much of Asia, where the delayed monsoon is finally delivering much-needed rain.

That didn’t deter some affluent Indians -– if the eclipse won’t come to them, they just went after it. They chartered an airplane to fly above the rain clouds to catch the once-in-a-lifetime eclipse. Each seat cost US Dollars 1,650.

It’s rarely that totality crosses through countries with such high human numbers as China and India. This time around, millions of people and thousands of journalists took advantage.

Some travelled long distances hoping to get the best view from the 200-km wide path of totality. Others watched it one of Asia’s many and cacophonous 24/7 TV news channels. The event had all the elements of a perfect television story: mass anticipation, eager experts and enthusiasts, occasional superstitions, uncertainties of weather and, finally, a stunning display of Nature’s raw power.

‘Darkness at Dawn!’ screamed a popular headline, referring to the eclipse causing a sudden ‘nightfall’ after the day had begun. Other superlatives like ‘Spectacle of the century’ and ‘A sight never to be missed’ were also widely used.

How I wish Asia’s media took as much interest in another kind of ‘eclipse’ that surrounds and engulfs us! One that does not end in minutes, but lasts for years or decades, and condemns millions to lives of misery and squalor.

Stories of poverty, social disparity and economic marginalisation are increasingly ‘eclipsed’ in Asia by stories of the region’s growing economic and geopolitical might.

The mainstream media in Asia –- as well as many outlets in the West — never seem to tire of carrying reports of Asia rising. Indeed, that is a Big Story of our times: many Asian economies have been growing for years at impressive rates. Thanks to this, over 250 million Asians have moved out of poverty during this decade alone. According to the UN’s Asian arm ESCAP, this is the fastest poverty reduction progress in history.

We see evidence of increased prosperity and higher incomes in many parts of developing Asia. Gadgets and gizmos –- from MP3 to mobile phones — sell like hot cakes. More Asians are travelling for leisure than ever before, crowding our roads, trains and skies. Lifestyle industries never had it so good. Even the current recession hasn’t fully dampened this spending spree.

But not everyone is invited to the party. Tens of millions of people are being left behind. Many others barely manage to keep up -– they must keep running fast just to stay in the same place.

National governments, anxious to impress their own voters and foreign investors, often gloss over these disparities. The poor don’t get more than a token nod in Davos. National statistical averages of our countries miss out on the deprivations of significant pockets of population.

For example, despite recent gains, over 640 million Asians were still living on less than one US Dollar a day in 2007 according to UN-ESCAP. Three quarters of the 1.9 billion people who lack safe sanitation are in Asia — that’s one huge waiting line for a toilet!

On the whole, the UN cautions that the Asia Pacific region is in danger of missing out the 2015 target date for most Millennium Development Goals – the time-bound and measurable targets for socio-economic advancement that national leaders committed to in 2000.

The plight of marginalised groups is ignored or under-reported by the cheer-leading media. For the most part, these stories remain forever eclipsed. Except, that is, when frustrations accumulate and blow up as social unrest, political violence or terrorism. Even then, the media’s coverage is largely confined to reporting the symptoms rather than the underlying social maladies.

As he noted in a recent essay: “Maternal mortality in parts of Nepal is nearly at sub-Saharan levels, but we are obsessed with politics. Hundreds of cotton farmers in India commit suicide every year because of indebtedness, but the media don’t want to cover it because depressing news puts off advertisers. Reading the region’s newspapers, you would be hard-pressed to find coverage of these slow emergencies.”

P N Vasanti, Director of the Delhi-based Centre for Media Studies which monitors the leading newspapers and news channels in India, laments how “development” issues such as health, agriculture and education are not even on the radar of popular news sources. Her conclusion is based on a content analysis of the six major Indian news channels during the run-up to the recent general election in India.

I have come across similar apathy in my travels across Asia trying to enhance television broadcasters’ coverage of development and poverty issues. As one Singaporean broadcast manager, running a news and entertainment channel in a developing country, told me: “I don’t ever want to show poor people on my channel.”

Don’t get me wrong. Trained as a science journalist, I can fully appreciate the awe and wonder of a solar eclipse. For years, I have cheered public-spirited scientists who join hands with the media to inform and educate the public on facts and fallacies surrounding these celestial events.

But there are more things in heaven and earth, than are dreamt of in our mainstream media’s breathless coverage of the march of capital. Journalists and their gate-keepers should look around harder for the many stories that stay eclipsed for too long.

* * * * * *

Shorter version of the above comment was published by Asia Media Forum on 23 July 2009

Full length version appeared on OneWorld.Net on 23 July 2009

Reprinted in The Nepali Times, 24 July 2009