This is the Sinhala text of my Ravaya column published on 13 Nov 2011, where I continue my discussion on the future of newspapers. I look at the last newspaper boom currently on in Asia, and caution that good times won’t last for long: take advantage of it to prepare for the coming (and assured) turbulence in the mainstream media!

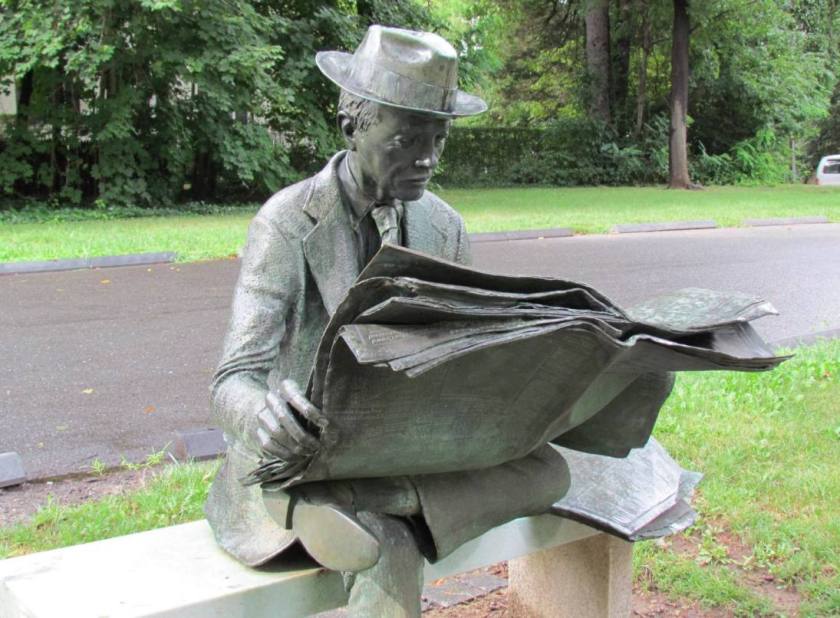

අප දන්නා විදියේ පුවත්පත්වලට වසර 400කට වැඩි ඉතිහාසයක් තිඛෙනවා. ලංකාවේ පුවත්පත් කලා ඉතිහාසයත් වසර 180ක් පමණ පැරණියි. තවමත් නිතිපතා ජනතාව අතරට යන පැරණිතම ජනමාධ්ය වන පුවත්පත්, 21 වන සියවසේ තාකෂණික හා ආර්ථීක අභියෝග ජය ගනියි ද? අප විවිධ පැතිකඩවලින් විග්රහ කරන ප්රශ්නය මෙයයි.

පුවත්පත් කර්මාන්තය සසල කරමින් ලොව බොහෝ රටවල මේ දිනවල පැතිර යන මාරුතය ගැන අප ගිය සතියේ කථා කළා. බටහිර රටවල පුවත්පත් සහ සගරා මිළදී ගැනීම සැළකිය යුතු අන්දමින් අඩු වී තිඛෙනවා. එයට වෙනස් ප්රවණතාවක් ආසියාවේ දක්නට ඇති බවත් සදහන් කළා. කුමක් ද මේ වෙනස?

2000 දශකය අවසන් වන විට ආසියාවේ පුවත්පත් සදහා වෙළදපොල ඉල්ලූම වැඩිවෙමින් තිබුණා. ලෝක පුවත්පත් සංගමය (World Association of Newspapers, WAN) එකතු කළ දත්තවලට අනුව, ලොව වැඩිපුර ම අලෙවි වන පුවත්පත් 10න් 9ක් ම ඇත්තේ ආසියාවේ – එනම් ජපානයේ හා චීනයේ. පත්තර ලෑලි හරහා හෝ දායකත්වය හරහා හෝ විකිණෙන පුවත්පත්වල (නොමිළයේ දෙන පුවත්පත් නොවෙයි) සමස්ත අලෙවිය සළකන විට අද ලෝකයේ විශාලතම පුවත්පත් වෙළදපොලවල් ඇත්තේ චීනය, ඉන්දියාව හා ජපානය යන රටවල් තුනේයි. සිවු වැනි තැනට එන්නේ අමෙරිකාවයි. (බලන්න: http://tiny.cc/Circ)

ලෝකයේ වෙනත් කලාපවල පාඨකයන් පුවත්පත් මිළදී ගැනීම අඩු කරන අතර ආසියාවේ එය වැඩි වෙමින් පවතින බව WAN සංඛ්යා ලේඛන පෙන්නුම් කරනවා. උදාහරණයකට 2008 වසරේ ඉන්දියානුවන් මිලියන 11.5ක් දෙනා ප්රථම වතාවට පුවත්පත් කියවන්නට පටන් ගත්තා. මේ ඇයි?

ආසියාවේ ආර්ථීක වර්ධනයත් සමග මධ්යම ජාතිකයන් සංඛ්යාව සීඝ්රයෙන් වැඩි වෙමින් පවතිනවා. ඉහළ යන ආදායම් මට්ටම් හා සාකෂරතා/අධ්යාපනික මට්ටම් සමග පුවත්පත් සදහා ඉල්ලූම වැඩි වනවා. එමෙන්ම පත්තරයක් දිනපතා මිළට ගැනීම යම් අන්දමකින් සමාජ තත්ත්වයක් පෙන්නුම් කරන බවට පිළිගැනීමක් ඉන්දියාව, ඉන්දුනීසියාව, තායිලන්තය වැනි රටවල තිඛෙනවා.

ජනගහනයට සාපේකෂව වැඩිපුර ම පුවත්පත් මිළදී ගන්නා රට ජපානයයි. ලෝකයේ සියළුම රටවල සියළුම භාෂාවලින් පළ කැරෙන පුවත්පත් අතර වැඩිපුර ම අලෙවි වන පුවත්පත් 5 හමුවන්නේ ජපානයේ. පත්තර කියවීම ජපන් ජාතිකයන් අතර ඉතා හොදින් මුල් බැස ගත් පුරුද්දක්. ලංකාවේ පුවත්පත් අලෙවිය පිළිබද නිවැරදි හා පැහැදිලි තොරතුරු සොයා ගැනීම අසීරුයි. කිසිදු පුවත්පත් සමාගමක් තම අලෙවි සංඛ්යා හෙළි කරන්නේ නැහැ. ඇතැම් රටවල මෙන් අපකෂපාතව මුද්රිත මාධ්ය ෙකෂත්රයේ දත්ත විග්රහ කරන පර්යේෂණායතන ඇත්තේ ද නැහැ.%

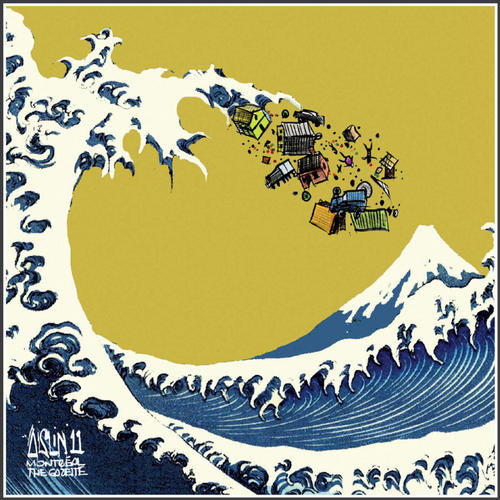

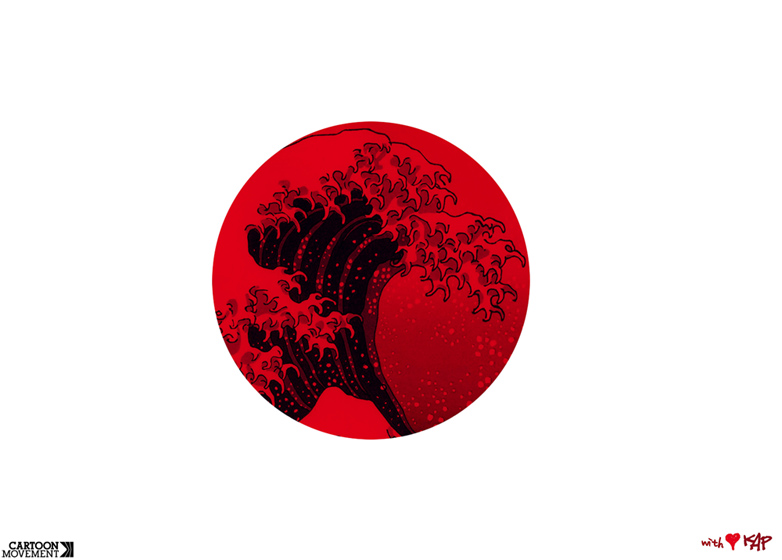

අප ආසියාවේ දැන් අත් විදින්නේ පුවත්පත් ප්රකාශන ලෝකයේ දැකිය හැකි වන අවසාන සරු කාලය (world’s last newspaper boom) බව ඇතැම් පර්යේෂකයන්ගේ මතයයි. පුවත්පත් පමණක් නොව ජන මාධ්ය හැමෙකක් ම පාහේ වැඩිපුරම පරිශීලනය වන්නේ ප්රචලිත වී ඇත්තේ ආසියාවේයි. එයට හේතුව (නොබෝදා බිලියන් 7 ඉක්මවා ගිය) ලෝක ජනගහනයෙන් සියයට 60ක් වෙසෙන්නේ ආසියාවේ වීමයි. තවත් හේතුවක් නම් පසුගිය දශක දෙක තුළ එතෙක් සංවෘතව තිබූ මාධ්ය වෙළදපොලවල් විවෘත වීම නිසා දෙස් විදෙස් ආයෝජන මාධ්ය ෙකෂත්රයට වැඩියෙන් ගලා ඒමයි.

මේ වත්මන් ප්රවණතා දෙස බලන විට අප නිගමනය කළ යුත්තේ සෙසු ලෝකයේ දැනට සිදුවන මාධ්ය වෙළදපොල ගරාවැටීම ආසියාවට නොඑන බව ද? වෙළදපොල පරිනාමීය ප්රවාහයන්ට ඔරොත්තු දිය හැකි තරම් ආසියානු මාධ්ය ආයතන ශක්තිමත් බව ද?

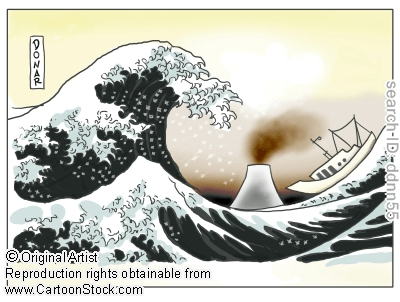

ගෝලීයකරණය වූ තොරතුරු සමාජය තුළ ලෝක ව්යාප්තව පැතිර යන සැඩ සුළංවලින් ආසියාවේ අපට මුළුමනින් ම ආරකෂා වී සිටිය හැකි යයි සිතීම ස්වයං මුලාවක්. 2009 අගදී මෙරට පුවත්පත් හිමිකරුවන්, කතුවරුන් හා ජ්යෙෂ්ඨ මාධ්යවේදීන් සිටි සභාවක් අමතමින් මා කියා සිටියේ ලෝක මට්ටමින් සිදු වන සන්නිවේදන ප්රවණතා මෙරටට පැමිණෙන්නට යම් තරමක ප්රමාදයක් ඇති බවයි.

උදහරණයකට ලෝකයේ ටෙලිවිෂන් විකාශයන් 1929දී (අමෙරිකාවේ) ඇරඹුණත් එය ලංකාවේ පටන් ගත්තේ 1979දී – එනම් වසර 50කට පසුව. එහෙත් වාණිජ මට්ටමේ ජංගම දුරකථන සේවා මුල්වරට (ජපානයේ) 1979දී ඇරැඹි දස වසක ඇවෑමෙන් 1989දී මෙරට මුල් ම ජංගම දුරකථන ජාලය ක්රියාත්මක වුණා. වාණිජ මට්ටමේ ඉන්ටර්නෙට් සේවා 1980 දශකය අගදී ලොව දියුණු රටවල ඇරැඹුණු අතර 1995දී ලංකාවත් සයිබර් අවකාශයට සම්බන්ධ වුණා.

මේ කාලාන්තරය එන්න එන්න ම කෙටි වීම අද තොරතුරුක සමාජයේ ගති සොබාවයි. එය ප්රවණතාවක් හැටියට ගතහොත් හොදට හෝ නරකට හෝ මාධ්ය හා තොරතුරු තාකෂණ ෙකෂත්රයේ ලොව ඇති වන නව රැලි නොබෝ දිනකින් ම අපේ දූපතටත් ළගා වනවා.

ලොව පුරා හමා යන මාධ්ය වෙළදපොල සැඩ සුළංවලින් අපව සුරැකෙන්නේ නැහැ. එයට තව වසර කිහිපයක් තුළ අපට ද මුහුණ දෙන්න සිදු වනවා. එහෙත් අපට උපක්රමශීලීව මේ ප්රමාදයෙන් ප්රයෝජන ගත හැකියි. වෙනත් දියුණු හා දියුණු වන රටවල මාධ්ය ආයතන මේ අභියෝගයට මුහුණ දෙන සැටි හා හැඩ ගැසෙන සැටි අප හොදින් අධ්යයනය කළ යුතුයි. ළග එන මාරුතයට මුහුණදීමට අපේ මාධ්ය පෙළ ගැසීම අවශ්යයි.

පුවත්පත් යනු කර්මාන්තයක් වුවත් එය අනෙකුත් වාණිජමය ව්යාපාරවලට වඩා සංකල්පමය හා ප්රායෝගික අතින් වෙනස්. පුවත්පතක අන්තර්ගතය නිර්මාණය වන්නේ පූර්ණකාලීන හා නිදහස් මාධ්යවේදීන් ගණනාවකගේ දායකත්වයෙන්. ප්රවෘත්ති, විචිත්රාංග, ඡායාරූප හා විද්වත් ලිපි ආදිය පුවත්පත් කාර්යාලයක් ඇතුළතින් මෙන් ම පිටතින් ද ජනනය වනවා. මේ සියල්ල සමානුපාතික කොට, නිසි පිටු සැළසුමක් සහිතව කලට වේලාවට මුද්රණය කරන්නටත්, එම පිටපත් රට පුරා කාර්යකෂමව ඛෙදා හරින්නටත් මනා සම්බන්ධීකරණයක් තිබිය යුතුයි. එමෙන්ම පුවත්පත් ආදායමට සම්මාදම් වන වෙළද දැන්වීම්කරුවන් සමග නිති සබදතා පවත්වා ගත යුතුයි.

වෙනත් භාණ්ඩ මෙන් නිපදවා ගබඩා කර ගැනීමේ හැකියාවක් පුවත්පත්වලට නැහැ. වඩාත්ම අළුත් පුවත් හා විග්රහයන් හැකි ඉක්මනින් පාඨකයන් අතට පත් කිරීමේ අභියෝගයට ලොව පුරා පුවත්පත් කාර්්යාලවල කර්තෘ මණ්ඩල මෙන්ම මුද්රණ හා ඛෙදා හැරීමේ සේවකයන්ද දිවා රෑ මුහුණ දෙනවා. කාලය සමග කරන මේ තරග දීවීමට සමාන්තරව ඔවුන් තමන්ගේ තාරගකාරී පුවත්පත් ගැන අවධානය යොමු කළ යුතුයි.

රටේ බල පවත්නා නීති, සදාචාරමය රීතිවලට ගරු කරමින් ඒ සම්මත රාමුව තුළ නැවුම් වූත්, සිත් ඇද ගන්නා වූත් පුවත්පතක් දිනපතා හෝ සතිපතා නිකුත් කළ යුතුයි. ඔබ මේ කියවන පත්තර පිටපත ඔබ අතට එන්නට බොහෝ දෙනකු නන් අයුරින් දායක වී තිඛෙනවා. බලා ගෙන ගියා ම පත්තරයක් කියන්නේ සුළුපටු ප්රයත්නයක් නොවෙයි!

එමෙන්ම පුවත්පත් යනු හුදෙක් මුද්රිත කොළ කෑලි සමූහයක් නොවෙයි. ප්රකාශන ඉතිහාසය මුළුල්ලේ දියුණු වී ආ සම්ප්රදායයන් හා ආචාරධර්ම රැසක් නූතන පුවත්පත් කලාවට තිඛෙනවා. ලෝකයේ හැම පුවත්පතක් ම එක හා සමාන අයුරින් මේවාට අනුගත වන්නේ නැහැ. එහෙත් පුළුල්ව පිළි ගැනෙන ‘පොදු සාධකයක්’ නම් පුවත්පත් නියෝජනය කරන්නේ හිමිකරුවන් හා දැන්වීම්කරුවන්ට වඩා පාඨකයන් ඇතුළු ජන සමාජය බවයි. මේ පොදු උන්නතිය (public interest) වෙනුවෙන් පෙනී සිටීම නිසා මාධ්ය ආයතනවලට හා ඒවාට අනුයුක්ත මාධ්යවේදීන්ට සමාජයේ සුවිශේෂ තැනක් ලැඛෙනවා.

මහජනයාට තොරතුරු දැන ගැනීමේ අයිතිය හා අදහස් ප්රකාශ කිරීමේ අයිතිය නියෝජනය කරන පුවත්පත් රැක ගැනීමට සිවිල් සමාජයේ නැඹුරුවක් තිඛෙනවා. සාමාන්ය මුද්රණාලයකට තබා පොත් මුද්රණය කරන ප්රකාශන සමාගමකටවත් නැති තරමේ ගෞරවයක් පුවත්පත් ආයතනවලට තවමත් ලැඛෙනවා. නමුත් මේ ඓතිහාසික සබැදියාව පලූදු වන ආකාරයේ බාල අන්තර්ගතයන් ඛෙදන්නට පටන් ගත් විට පාඨකයන් එබදු පුවත්පත් මිළට ගන්නට (හෝ නිකම් දුන්නත් කියවන්නට) කැමැති වන්නේ නැහැ.

අමෙරිකානු මාධ්ය ආයතනවල අනාගතය ගැන 1993දී ප්රකට ලේඛකයකු කළ අනාවැකියක් ගැන අප ගිය සතියේ සදහන් කළා. පාඨක විශ්වාසය ගරා වැටෙන බව දැන ගත් ඇතැම් මාධ්ය ආයතන තමන්ගේ ප්රකාශන කියවීමට විවිධාකාර ත්යාග පවා දීමට පටන්ගෙන තිඛෙනවා. මේ ආකාරයේ ‘අල්ලස්’ හා ‘සීනිබෝල’වලින් බහුතර පාඨකයන් රවටන්නට අමාරුයි. මොන උපක්රම යොදා ගත්තත් පාඨකයන්ගේ විශ්වාසය නොමැතිව වැඩි කල් පවතින්නට කිසිදු පුවත්පතකට බැහැ.

පත්තරයක් කියන්නේ මහජන මනාපය දිනපතා ම හෝ සති අගදී හෝ නිරතුරුව පතන හා ලබන ප්රකාශනයක්. මේ මනාපය දිගින් දිගට පවත්වා ගැනීමේ අභියෝගයක් තිඛෙනවා. එය තරගකාරී වෙනත් පුවත්පත් සමග පමණක් ඇති තරග දිවීමක් නොවෙයි. පත්තරවලට වඩා ඉක්මනින් ප්රවෘත්ති රටට දීමේ හැකියාව රේඩියෝ, ටෙලිවිෂන් හා ඉන්ටර්නෙට් මාධ්යයන්ට තිඛෙනවා. ඒ විද්යුත් මාධ්යවල ව්යප්තියත් සමග තමන්ගේ අන්තර්තය හා මුහුණුවර වෙනස් කරන්නට බොහෝ පුවත්පත්වලට පසුගිය දශක දෙක තුළ සිදුවුණා.

විද්යුත් මාධ්ය ඉක්මන් වූවත් යමක් ගැඹුරින් විග්රහ කිරීමේ ඉඩකඩ සීමිතයි. මේ නිසා ලොව පුරා පුවත්පත් තනිකර ප්රවෘත්ති ආවරණයට වඩා අද උත්සාහ කරන්නේ ප්රවෘත්ති විග්රහ කිරීමටයි. ප්රවෘත්ති බවට පත් වන සිදුවීම් සමාජයේ විවිධාකාර ප්රවාහයන්ගෙන් මතු වන නිසා පිටුපසින් ඇති සාධක හා ප්රවණතා මනා සේ හදුනාගැනීම සංකීර්ණ සමාජයක වෙසෙන අප කාටත් වැදගත්. මේ ප්රවාහයන් ගැන පර්යේෂකයන්, සමාජ සේවකයන් හා විද්වතුන් කරන විග්රහවලට දැන් පුවත්පත් හා පුවත් සඟරාවල වැඩි තැනක් ලැඛෙනවා. අද බටහිර ඇතැම් පුවත්පත් Newspaper යන නමට සමාන්තරව Viewspaper යන නම ද තමන් හැදින්වීමට යොදා ගන්නවා.

මෙකී නොකී සියල්ල මා දකින්නේ පරිනාමීය හැඩ ගැසීම් හැටියටයි. වඩාත් සවිමත් උචිත වූ ජීවීන් ඉතිරි කරමින් දුර්වලයන් වඳ කර දමන ජෛවීය පරිනාමය මෙන් ම තොරතුරු සමාජයේ ද පරිනාමීය බලවේග ක්රියාත්මක වනවා. එහෙත් ජෛව පරිනාමයට වඩා එය සියුම් හා බුද්ධිගෝචරයි. මාධ්ය ග්රාහකයන්ට හරවත්, ප්රයෝජනවත් දෙයක් සිත් කාවදින අයුරින් ඉදිරිපත් කරන පුවත්පතකට අද මහා තොරතුරු ප්රවාහයේ නොගිලී පවතින්නට ඉඩක් ඇතැයි මා විශ්වාස කරනවා.