“In the struggle for freedom of information, technology — not politics — will be the ultimate decider.”

These words, by Sir Arthur C Clarke, have been cited in recent days and weeks in many debates surrounding WikiLeaks, secrecy and the public’s right to know.

I invoke these words, and many related reflections by the late author and futurist, in a 2,250-word essay I have just written. Titled Living in the Global Glass House, it is presented in the form of an Open Letter to Sir Arthur C Clarke. It has just been published by Groundviews.org

This is my own attempt to make sense of the international controversy – and confusion – surrounding WikiLeaks. Taking off from the current concerns, I also look at what it means for individuals, corporations and governments to live in the Age of Transparency that has resulted from the Information Society we’ve been building for years.

This is my own attempt to make sense of the international controversy – and confusion – surrounding WikiLeaks. Taking off from the current concerns, I also look at what it means for individuals, corporations and governments to live in the Age of Transparency that has resulted from the Information Society we’ve been building for years.

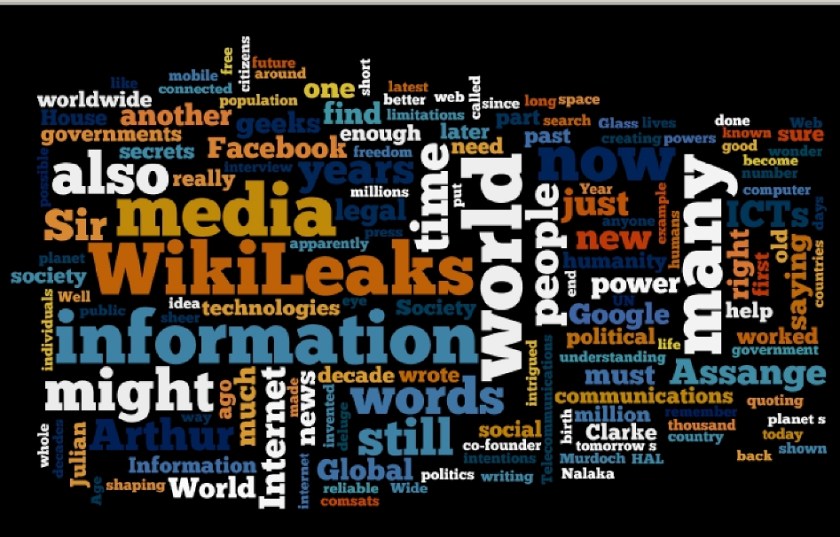

Sir Arthur foresaw these developments year or decades ago, and wrote perceptively and sometimes in cautionary terms about how we can cope with these developments. As a research assistant and occasional co-author to Sir Arthur from 1987 to 2008, I had the rare privilege of sharing his views firsthand. In this essay, I distill some of the best and most timely for wider dissemination. The above Wordle graphic illustrates the keywords in my essay.

The essay was also prompted by recent experiences. Here’s that story behind the story:

By happy coincidence, I arrived in London on 28 November 2010, the very day the WikiLeaks Cablegate erupted all over the web, beginning to spill out what would eventually be over 250,000 secret international ‘cables’ within the US diplomatic corps.

The Guardian UK that day published an interactive map-based visualization of the leaks. By moving the mouse over the map, readers can find key stories and a selection of original documents by country, subject or people

During the week I spent in London, I experienced not only uncharacteristically early and intense snow storms, but a mounting international storm on the web over the leaked cables. WikiLeaks’ co-founder and chief editor Julian Assange was also somewhere in the UK, playing cat and mouse at the time with the Swedish police and Interpol. (He later turned himself in to the British authorities.)

Soon after I returned to Colombo, Transparency International Sri Lanka asked me to speak at a workshop on the right to information they had organised for journalists. Given my reputation as a geek-watcher and commentator on the Information Society, they asked to talk about what WikiLeaks means for investigative journalism. Two days later, the Ravaya newspaper did a lengthy interview with me on the same topic which they have just published in their issue for 19 December 2010.

All these elements and experiences combined in writing this essay. Being confined to home by a nasty cold and cough also helped! In fact, on 16 December when Sir Arthur’s 93rd Birth Anniversary was marked, I was too weak to even step out of the house to visit his gravesite. In the end, I finished writing this Open Letter to him on the evening of that day.

My daughter Dhara and I would normally have taken flowers to Sir Arthur’s grave on his birth anniversary. This year, instead, I offer him 2,250 words in his memory. The fine writer would surely appreciate this tribute from a small-time wordsmith.

Read Living in the Global Glass House: An Open Letter to Sir Arthur C Clarke

Compact version published in Daily Mirror, Sri Lanka, on 21 Dec 2010