Rodney Jonklaas (1925-1989) was a Lankan marine biologist, free diver, SCUBA diver, spearfisherman and underwater photographer. He was one of the pioneer divers in Ceylon, starting soon after the aqualung was invented in the 1940s. He was founder in 1946/7 of the “Reefcombers of Ceylon”, one of the world’s earliest diving clubs.

I have written about Rodney as my latest Ravaya newspaper column (published on 8 July 2018).

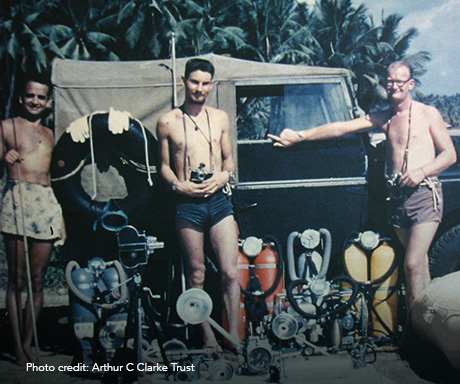

Rodney was one of two persons that author and diver Arthur C Clarke (1917-2008) met on his very first visit to Colombo when the latter’s ship SS Himalaya – taking him from London to Sydney, to explore the Great Barrier Reef – paused at Colombo Harbour for a few hours in December 1954. Rodney suggested that Clarke should come back to explore the Indian Ocean around Ceylon. Acting on this suggestion, Clarke returned in 1956 with fellow Englishman Mike Wilson to explore the island’s marine, cultural and natural heritage for several months. At the end of that expedition, both men decided to settle down in Ceylon. The rest is history.

Rodney was an integral part of the duo’s diving and undersea exploration activities which led, among other things, to their discovering a sunken ship off the southern coast of Sri Lanka full of Mughal silver coins, and making of Ceylon’s first colour movie (Ran Muthu Duwa, 1962) part of which was filmed underwater.

In the ensuing years, Rodney continued to work as a professional diver, taking on commercial assignments while also engaging in recreational diving and going in search of shipwrecks. I quote Rex I de Silva, a senior diver who was mentored by Rodney, who says Rodney was a keen marine conservationist and also a leading spearfisherman with several international records. Rex remembers Rodney as a Renaissance Man who was versatile and accomplished in a wide range of pursuits both on land and underwater.

I also draw on my interview with Rodney Jonklaas done in late 1984, when I met him in connection with a series of articles on humans and the ocean that I researched and wrote for the (now defunct) Kalpana Sinhala monthly magazine (February 1985 issue).

පුරෝගාමී ලංකික කිමිදුම්කරු රොඩ්නි ජොන්ක්ලස් (1925 – 1989) ගැන මා මීට පෙර විටින් විට සඳහන් කොට තිබෙනවා. ඒ ආතර් සී. ක්ලාක් සමග එක්ව මෙරට අවට මුහුදේ කිමිදුම් හා ගවේෂණ කිරීම සම්බන්ධයෙන්.

බර්ගර් ජාතිකයකු වූ රොඩ්නි විචිත්ර වූත්, අසාමාන්ය වූත් චරිතයක්. ඔහුගේ පරම්පරාවේ මෙරට සිටි ප්රවීණතම සමුද්ර ජීව විද්යාඥයා (marine biologist) වූ ඔහු ජීවිතයෙන් වැඩි කලක් තිස්සේ මෙරට අවට මුහුදේත් ගංගා හා වැව්වලත් කිමිදීමේ නිරත වුණා.

1954 දෙසැම්බර් 12 වනදා ආතර් ක්ලාක් සහ තවත් මගීන් රැසක් රැගත් ‘හිමාලයා‘ නම් නෞකාව පැය කිහිපයකට කොළඹ වරායේ නතර කරණු ලැබුවා. එය එංගලන්තයේ සිට ඔස්ට්රේලියාව බලා යන චාරිකාවක කෙටි විරාමයක්. එවකට ගුවන් ගමන් ප්රචලිතව තිබුණේ නැහැ.

ඒ කෙටි කාලය තුළ ගොඩබිමට පැමිණි ක්ලාක් මෙරට වාසය කරමින් සිටි මේජර් රෝලන්ඩ් රේවන්-හාට් නම් බ්රිතාන්ය ජාතිකයා සහ රොඩ්නි ජොන්ක්ලස් මුණ ගැසුණා. මෙරට පිළිබඳව දැඩි කුතුහලයක් ඔහු ඇති කර ගත්තේ මේ දෙදෙනා සමග කථාබහ කිරීමෙන්.

එවකට තරුණ වියේ සිටි රොඩ්නි දෙහිවල සත්වෝද්යානයේ සහකාර අධිකාරී ලෙස රැකියාව කළත් ඔහු වඩාත් ප්රකටව සිටියේ දිවයිනේ දක්ෂතම කිමිදුම්කරුවා ලෙසයි.

ක්ලාක් ඔස්ට්රේලියාවට යමින් සිටියේ ලෝ ප්රකට මහා බාධක පරය (Great Barrier Reef) නම් ලොව විශාලතම කොරල්පර පද්ධතිය අවට කිමිදුම් ගවේෂණවලටයි. ප්රමාණයෙන් එතරම් සුවිසල් නොවූවත් විසිතුරු කොරල්පර රැසක් ශ්රී ලංකාවට සමීප මුහුදේ හමු වන බවත්, ඊට අමතරව මුහුදුබත් වූ නෞකා රැසක් ද තිබෙන බවත් රොඩ්නි ක්ලාක්ට කීවා.

‘මේ උතුරු ඉන්දියන් සාගරයේ කොරල්පර හා වෙනත් ස්ථාන බොහෝමයක් තවම කිසිදු කිමිදුම්කරුවකු නොගිය තැන්. ඊළඟට ඔබේ කිමිදුම් ගවේෂණ සඳහා ලංකාවට එන්න’ යයි රොඩ්නි ක්ලාක්ට යෝජනා කළා.

එම යෝජනාව පිළිගත් ක්ලාක් හා ඔහුගේ කිමිදුම් සගයා වූ මයික් විල්සන් 1956දී මෙරට මාස කීපයක් ගවේෂණයට ආ සැටිත්, එය අවසානයේ දී මොවුන් දෙදෙනාම මෙරට පදිංචි වීමට තීරණය කළ සැටිත් ප්රකටයි.

රොඩ්නි ජොන්ක්ලස් මා මුල් වරට හමු වූයේ 1984 අගදී. ‘කල්පනා’ සඟරාවට ‘සාගරය සහ මිනිසා’ නමින් කවරයේ කතාවක් ලිවීමට එහි කර්තෘ ගුණදාස ලියනගේ එවකට පාසල් සිසුන් වූ පාලිත ගුණවර්ධනට හා මට පවරා තිබුණා. එහි එක් ලිපියක් අප ලිව්වේ රොඩ්නි ගැනයි. ජාඇල පිහිටි ඔහුගේ නිවසේ අප වරුවක් ගත කළා.

රොඩ්නි ස්ට්රැටන් ලුඩොවිසි ජොන්ක්ලස් උපන්නේ 1925දී මහනුවර. ත්රිත්ව විද්යාලයේ ඉගෙනීම ලබන අතර මහනුවර උඩවත්ත කැලේ වැවක පිහිනන්නට උගත්තා. පසුව ඔහු ලේවැල්ලේදී මහවැලි ගෙඟ්ත්, නුවර වැවේත් පිහිනුවා.

ඒ අවධියේ නුවර වැවේ පිහිනීම තහනම් කර තිබුණා. මේ නිසා ඔරුවක් පැදගෙන නුවර වැව මැද්දට ගිය රොඩ්නි එය ඕනෑකමින් පෙරළා, ආපසු පීනාගෙන ගොඩට ආවාලු!

පිහිනීමෙන් පසු ඔහු යොමු වුණේ කිමිදීමට. ”මගේ මුල්ම කිමිදුම් අත්දැකීමත් හරියට සුරංගනා කතා වගේ…දවසක් මම නුවර වැව රවුම දිගේ ඇවිදගෙන යනකොට එක කාන්තාවක් වැව අද්දරට වෙලා බොහොම දුකෙන් කල්පනා කරමින් හිටියා. මොකද අහපුවම කිව්වේ ‘මගේ ඔරලෝසුව වැවට වැටුණා’ කියලයි. මම ඒ වෙලාවෙම වැවට පැනලා වැව පතුළට කිමිදීගෙන ගිහින් ඔරලෝසුව සෙව්වා. උඩට ආවේ ඇගේ ඔරලෝසුවත් සොයා ගෙනයි. මේ මුල්ම කිමිදුමට මට කිසිම බාහිර උපකරණයක් තිබුණේ නැහැ…”

එදා ඒ අහම්බෙන් සිදු කළ මුල්ම කිමිදුමෙන් පසු රොඩ්නි දිය යට ලෝකය කෙරෙහි නොබිඳුණු ආදරයකින් බැඳුණා.

”මම මුහුදේ පීනන්න ඉගෙන ගත්තේ 1940 ගණන්වල කොළඹ සරසවියට ඇතුල් වීමෙන් පස්සෙයි. මහනුවර ඉඳන් කොළඹ ආවාට පහුවදාම මම කොළඹ කින්රොස් පිහිනුම් සමාජයට බැඳුණා. ඒ කාලේ දැන් වගේ කිමිදුම් කට්ටල තිබුණේ නැහැ. ජෑම් ටින්වලට රබර් පටිවලින් වීදුරු හයි කරලා, තනිවම හදා ගත්ත කණ්ණාඩි දමා ගෙන මූද යටට පිහිනුවා. මොන දුෂ්කරතා තිබුණත් කිමිදුම්කරුවකු වීමේ අධිෂ්ඨානය අත හැරියේ නෑ!”

කොළඹ සරසවියේ ජීව විද්යාව, රසායන විද්යාව හා භූගෝල විද්යාව හැදෑරු ඔහු ඉන් පිට වෙනවාත් සමගම දෙහිවල සත්වෝද්යානයට බැඳී, වසර 6ක් එහි සහකාර අධ්යක්ෂවරයකු ලෙස සේවය කළා. ඔහු එයින් ඉවත් වුණේ වැඩි නිදහසකින් යුක්තව කිමිදුම් කටයුතුවල යෙදෙන්නයි.

සම්පත් සීමිත ඒ කාලයේ රොඩ්නි මහත් උත්සාහයෙන් දිය යට හැම ශිල්ප ක්රමයක්ම උගත්තා. ”මයික් විල්සන් තමයි මට මුහුද යට ඡයාරූප ගැනීම හා චිත්රපට කැමරාකරණය ඉගැන්නුවේ” ඔහු සිහිපත් කළා.

විල්සන්, ක්ලාක්, ජොන්ක්ලස් ත්රිත්වය ලංකාවේ කිමිදුම් හා මුහුද යට ඡායාරූප ශිල්පයේ පුරෝගාමින්. අපේ සාගර යට විචිත්රත්වය අලලා නිපද වූ මුල්ම වාර්තා චිත්රපටය වූ Beneath the Seas of Ceylon (1958) තැනුවේ මේ තිදෙනායි. කාලයාගේ ඇවෑමෙන් මෙහි එකදු පිටපතක්වත් ඉතිරි වී නැහැග

ලංකාවේ රූපගත කළ විදේශීය චිත්රපට ගණනාවකට තාක්ෂණික පැත්තෙන් සහය වූ රොඩ්නි 1962දී මෙරට නිෂ්පාදිත මුල්ම වර්ණ චිත්රපටය වූ ‘රන්මුතු දූව’ චිත්රපටයේ මුහුද යට දර්ශන රූපගත කළා.

”රන්මුතු දූව චිත්රපටයේ මම ගාමිණි ෆොන්සේකා එක්ක මුහුද යට සටන් කරනවා. ඊට පස්සේ සීතාදේවී හා වාලම්පූරිය චිත්රපටවලත් මුහුද යට දර්ශන රූපගත කළා. මේ හැරෙන්නට මම ඉන්දියාව, සිංගප්පූරුව, මාලදිවයින වැනි රටවල් ගණනාවක මුහුද යට ලෝකය ගැන මා සම්බන්ධ වූ වාර්තා චිත්රපටවලට ජාත්යන්තර ප්රසංසාව පවා හිමි වුණා.”

සත්තු වත්තෙන් ඉවත් වූ පසු මුතු බෙල්ලන් කැඩීමේ හා විසිතුරු මසුන් පිටරට යැවීමේ යෙදී සිටි රොඩ්නි කිසි විටෙකත් කිමිදීම අත් හැරියේ නැහැ.

මුහුද යට ලෝකය විසිතුරු මෙන්ම අන්තරාදායක ද බව ඔහු දැන සිටියා. ”මට අත්දැකීම් ගොඩක් තියනවා. එයින් වඩාත්ම රසවත් වෙන්නේ වඩාත්ම මරණයට කිට්ටු වුණු අවස්ථාවයි. වතාවක් මම ත්රිකුණාමලයේ කලපුවේ ගල්පර අසල කිමිදෙමින් ඉන්න කොට විශාල මෝරෙක් මාව හපා කන්න එළවාගෙන ආවා. මට මෝරත් එක්ක හරි හරියට පීනන්න පුළුවන් වුණේ නැහැ. ළඟ තිබුණු ගල් පරයකට මුවා වෙලා මම ඉනේ තිබුණ යකඩ කූරක් අතට ගත්තා. මෝරා හොඳටම ළං වුණාම ඒකෙන් ඌව තල්ලු කරලා දැම්මා. පුදුමයකට වගේ ඌ යන්න ගියා. මට තාමත් හිතෙන්නේ ඌ එදා මාව බොරුවට බය කළා කියලයි. ඕනෑ නම් මාව හපා කන්න ඌට ඉඩ තිබුණා….”

සාගරය ගැන ඔහුගේ සිතේ තිබුණේ බිය මුසු කනගාටුවක්. ජනගහනය වැඩි වීමත්, මිනිසාගේ අදූරදර්ශි ක්රියාත් නිසා සාගරය බෙහෙවින් දූෂණය වෙමින් ඇති බව ඔහු පෙන්වා දුන්නේ 1960 ගණන්වල පටන්මයි.

”යමක් කමක් කරන්නට පුළුවන් වූ දා ඉඳලා මිනිසා විසින් කළේ සාගරයෙන් හැකි තරම් පල නෙළා ගැනීම. අද වෙලා තියෙන්නේ අක්රමවත් ලෙස සාගර අස්වනු නෙළන්නට යාමෙන් ලොකු පිරිහීමක් ඇති වීමයි. මසුන් මරනවා කියන්නෙත් සාගර සම්පත් වැනසීමක්. ඒ කියන්නේ මාළු කන්න එපා කියන එක නොවෙයි. අපේ රටේ ධීවර කර්මාන්තය විශාල ජනතාවකගේ ජීවනෝපාය වී තිබෙනවා. මේ නිසා මෙය ක්රමවත්ව පාලනය කිරීම ලේසි නෑ. ටිකෙන් ටික වුණත් අපි මසුන් බෝ කිරීමේ පැත්තට හැරෙන්න ඕනෑ. ඒ වගේම ගැඹුරු මුහුදු ධීවර සම්පත් වඩා ප්රයෝජනයට ගත යුතුයි. අනෙත් අතට මාළු කියන්නේ එක් සමුද්ර සම්පතක් පමණයි. ඒ ගැන පමණක් සිතා කටයුතු කිරීම වැරදියි.”

අවුරුදු 35ක් තිස්සේ ලංකාව වටා ඇති සාගරයේ කිමිදීමේ යෙදී ඇති රොඩ්නි ජොන්ක්ලස් එම කාලය තුළ ඇති වී තිබෙන සාගර දූෂණය හොඳ හැටි දුටුවා.

”ලංකාව අවට මුහුදේ සිටින සතුන් හා ශාකවල පැවැත්මට තර්ජනයක් එල්ල කරන එක් සාධකයක් සාගර දූෂණය. අපි ඔක්කොම කැලිකසළ ගොඩ ගසන්න පුළුවන් අසීමිත ‘කුණු වළක්’ හැටියට සාගරය සලකන්නේ. අනෙක් අතට දූෂණය දැන් අභ්යන්තර (මිරිදිය) ජලාශවලටත් බලපානවා.”

”අද ලංකාවේ මුහුදුවල ඉන්න සමුද්ර ජීවීන් වඳ වී යන්නට පටන් අරන්. මුහුදු ඌරා (Dugong) වඳ වී යාමේ තර්ජනයට බෙහෙවින් ලක් වූ සතෙක්. ඩොල්පින්, කැස්බෑවන්, පොකිරිස්සන් වර්ග නීතියෙන් ආරක්ෂිත සතුන් වුවත් මසුන් මරන්නන්ගේ දැල්වලට හසු වෙනවා. බොහෝ විට මෙය ධීවරයන් වුවමනාවෙන් කරන දෙයක් නොවෙයි. ක්රමවත්ව පාලනය කරන සමුද්ර අභයස්ථාන (Marine Sanctuaries) අවශ්ය මේ නිසයි. විනාශ වී ගෙන යන සමුද්ර ජීවී සම්පත් බේරා ගන්නට තවමත් ඉඩ තිබෙනවා.”

ඔහු මේ ටික කීවේ මීට 34 වසරකට පෙර. ඔහු මිය ගොස් දශක තුනක් ගෙවීමට ආසන්න මේ වන විට තත්ත්වය තවත් උග්ර වෙලා. දේශගුණ විපර්යාසත් දැන් සාගර පරිසරයට පීඩන වැඩි කරනවා.

ඔහු රොඩ්නි සිහිපත් කරන්නේ බහුවිධ හැකියාවක් තිබූ, බොහෝ දේට දක්ෂ වූ අසාමාන්ය චරිතයක් ලෙසයි. ”මුහුදු ජීවීන් ගැන පුළුල් ප්රායෝගික දැනුමක් තිබූ ඔහු විසිතුරු මසුන් මෙන්ම විසිතුරු පැලෑටි ගැනත් බොහෝ සෙයින් අධ්යයනය කළා. ඉලක්කයට වෙඩි තබන්න, සංගීතයට, ලේඛන කලාවට මෙන්ම විනෝදකාමී ලෙස කතා කියන්නත් අති සමතෙක්.”

එසේ වුවද රොඩ්නිගේ චරිතයේ යම් පරස්පරයක් ද තිබූ බව රෙක්ස් කියනවා.

”එක් අතකින් රොඩ්නි නිර්ව්යාජ සංරක්ෂණවේදියෙක්. මෙරට මසුන් ඇල්ලීමට ඩයිනමයිට් භාවිතයට එරෙහිව ආතර් සී. ක්ලාක් සමග එක්ව ඔහු දිගටම උද්ඝෝෂණ කළා. එසේම කොරල් කඩා හුණුගල් ලෙස පිළිස්සීමට එරෙහිව මේ දෙදෙනා වසර ගණනක් ගෙන ගිය සංරක්ෂණ අරගලය අන්තිමේදී සාර්ථක වුණා. මන්නාරමේ බොක්කේ ඉතිරිව සිටින මුහුදු ඌරන් රැක ගන්නට රොඩ්නි හඬ නැගුවා.”

අනෙක් අතට රොඩ්නි කිමිදුම්කරුවකු ලෙස දිය යට හෙල්ලකින් ඇන මසුන් මැරීමේ සමතෙකු වූ බව රෙක්ස් සිහිපත් කරනවා. දැල් නොමැතිව, තනි තනිව මුහුද යට මසුන් ඇල්ලීමට ජාත්යන්තරව පනවා ඇති මාර්ගෝපදේශවලට අනුකූලව ඔහු මෙය කළ බවත්, ඉන්දියානු සාගර කලාපයේම කිමිදුම්කරුවන් අතර හොඳම ඉලක්කයක් තිබූ බවක් රෙක්ස් කියනවා.

වරක් යම් කිසිවකු රොඩ්නිගෙන් විමසා ඇත්තේ ”ඔබ සංරක්ෂණයට වැඩ කරන අතර මසුන් මරන්නේ ඇයි?” කියාය. රොඩ්නිගේ උත්තරය,”ඔබ මාළු කනවාද? මාළු ඔබට කෑමට නම් කවරකු හෝ මාළු ඇල්ලිය යුතුයි. මාළු අනුභව කරන කිසිවකුටත් මාළු ඇල්ලීම ගැන විවේචනය කළ නොහැකියි.”

රොඩ්නිට මාළු පිළිබඳව හොඳ ඇසක් හා තීක්ෂණ දැනුමක් තිබුණා. අපේ දූපත අවට මුහුදේ මත්ස්ය විශේෂ ගණනාවක් මුල් වරට හඳුනා ගත්තේ ඔහුයි. මුහුදු සර්පයන් ගැන ඔහු විශේෂ උනන්දුවක් දැක්වූවා. රෙක්ස් කියන හැටියට, ”අපේ මුහුදුවල සිටින මුහුදු සර්ප විශේෂ හැම එකක්ම විෂ සහිතයි. එහෙත් ආක්රමණශීලී නැහැ. මේ බව තේරුම් ගත් රොඩ්නි, අවදානමකින් තොරව ඔවුන්ට සමීප වෙමින් දිය යටදී ඔවුන් අධ්යයනය කළා.”

රොඩ්නි සිය දැනුම පොත් කිහිපයකට ගොනු කළත් ඔහුට තවත් බොහෝ දේ ලිවිය හැකිව තිබූ බව රෙක්ස්ගේ අදහසයි.

”රොඩ්නි කිමිදුම්කරුවකු ලෙස වාණිජමය වැඩත් කළා. මේ නිසා ශාස්ත්රීය හෝ විද්යා පොත පත ලියන්නට කාලය සීමිත බව ඔහු මට කීවා. 1980 ගණන්වල මෙරට මුහුදු මෝරුන් පිළිබඳ විස්තරාත්මක හා රූපමය පොතක් ලිවීම මා ආරම්භ කළ විට එයට බොහෝ සෙයින් උපකාර කර මා දිරි ගැන්වූවා” රෙක්ස් කියනවා.

රොඩ්නි මිරිදිය මසුන් ක්ෂේත්රයට ලබා දුන් දායකත්වය වෙනුවෙන් මිරිදිය මසුන් විශේෂ දෙකක් නම් කර තිබෙනවා.

රොඩ්නිගේ දහස් ගණනක් කිමිදුම් චාරිකා අතරින් රෙක්ස් වඩාත් සුවිශේෂී ලෙස සලකන්නේ 1942දී ජපන් ගුවන් හමුදා ප්රහාරයකට ලක්ව අපේ නැගෙනහිර වෙරළට ඔබ්බෙන් මුහුදුබත් වූ හර්මිස් නම් බ්රිතාන්ය යුද්ධ නැවේ පිහිටීම සොයා ගැනීමයි.

එම නැවේ කතාවත්, 1967දී රොඩ්නි ජොන්ක්ලස් මහත් උත්සාහයෙන් එය මුහුදු පත්ලේ සොයා ගැනීමත් වෙනම කිව යුතුයි.

See also previous columns: