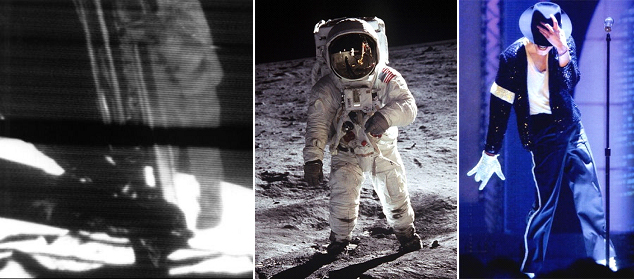

When Armstrong stepped on the Moon, he said: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind“. Man on the Moon was very much the news highlight of 1969, and at the time, the term ‘mankind’ was understood to include women as well. The more gender-neutral term ‘humankind’ would come into popular use some years later.

Beginning with Apollo 11, the Apollo programme landed a dozen astronauts on the Moon, all of who returned safely – as did the astronauts of the disaster-stricken mission, Apollo 13. Without exception, all of them were white and male. While they were all highly qualified, disciplined and trained men who had worked long and hard to earn their places in history, they did not fully represent the diversity of their nation, let along of the planet whose emissaries they were portrayed to be.

Women, celebrated across cultures as holding half the sky, took a long time to travel beyond the sky to outer space.

Although a Russian (Valentina Tereshkova) had become the first woman in space early on in 1963, it took the Americans another 20 years to have their first woman astronaut: Sally Ride, who traveled to Earth orbit on the Space Shuttle in June 1983.

A recent British documentary reveals how America could have sent a woman to the Moon during the Apollo programme. It reveals, belatedly, one of history’s great might-have-beens.

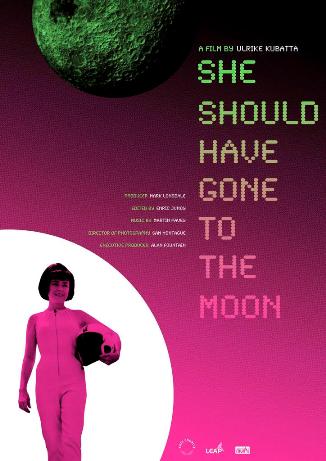

She Should Have gone To The Moon (58 mins, 2008), written and directed by Ulrike Kubatta isn’t quite story that the American space agency NASA would like to be reminded of as it marks Apollo 11’s 40th anniversary.

Truhill tells how the women outperformed men in all the training tests (including water tank isolation) but how ultimately, the authorities, with the approval of President Johnson, stipulated that they would “rather send monkeys into space than a woman”.

In the film, the tough talking and sharp witted Jerri Truhill looks back at her compelling life via a phone call with the film-maker. This conversation becomes the catalyst for the director’s imagining of key events in Truhill’s potent narrative and inspires a journey to meet the heroine in Texas. Along the way the film-maker places herself in Truhill’s story, first wandering across the surreal landscape of White Sands and then suspended in zero gravity inside a water tank.

Included are staged scenes, dreamt-up moments from Truhill’s story, which evoke the popular melodrama of 1950s American cinema. These fictional moments bridge the gaps of time and distance between the filmmaker and her subject. Their stylised and dreamlike quality is counterpointed by shots from both Truhill’s and NASA’s film archive. The various strands produce the film’s heady timeline, as they circle through real and imagined spaces, past and present.

I can’t locate any part of the film that allows embedding on to WordPress blog platform. But you can watch official trailer for She should have gone to the Moon on IMDB

On LEEDVD.TV’s YouTube channel, I found this segment of another documentary named Rocket Girl, but Google does not bring up too much other info about this film.

Watch Rocket Girl, part 1

Read American National Public Radio’s coverage: Women’s Space Dreams Cut Short, Remembered

Read NASA’s own website profiles of women’s accomplishments in space

Seven of the “Mercury 13” gathered at the Kennedy Space Center in 1995. In the photo below, from left to right, are: Gene Nora Jessen, Wally Funk, Jerrie Cobb, Jerri Truhill, Sarah Rutley, Myrtle Cagle and Bernice Steadman. They came to watch Eileen Collins become the first woman to pilot a space shuttle. NASA has come a long way.

As I wrote in May 2009, the path-breaking TV series Star Trek, which started airing on television in the US in September 1966, was way ahead of reality. When neither the mainstream television nor the space programme reflected America’s true diversity, Star Trek created a multi-ethnic crew for the Starship Enterprise, roaming the universe in the 23rd century. It included an African-American woman, a Scotsman, a Japanese American, and a super intelligent alien, the half-Vulcan Spock.

Reality took a long time catching up. It was only in August 1983 that Guion “Guy” Bluford, Jr., became the first black American astronaut. Another nine years passed before Dr. Mae Jemison became the first African-American woman to go to space, when she joined a Space Shuttle mission in September 1992. In fact, she cited Star Trek character Uhura as an influence in her decision to pursue a career in space.

Multi-cultural crews did not become commonplace until the late 1990s, when the International Space Station became operational. Space travel has yet to reach the utopian ideals of Star Trek.

Images related to ‘She should have gone to the Moon’ courtesy Ulrike Kubatta. Other images courtesy NASA