That was probably true for the 19th century in which he lived and died, but it takes a bit more than a mousetrap to generate a buzz these days. But simple and elegant inventions are still the best. BigShot is one of these.

It’s still in testing stage, but already being hailed as “a camera that could improve the way children learn about science and one another”.

BigShot is an innovation by Indian-born Shree K. Nayar, now the T. C. Chang Professor of Computer Science at Columbia University in New York, USA.

As his university’s newspaper reports: “He came up with a prototype as sleek as an iPod and as tactile as a Lego set: the Bigshot digital camera. It comes as a kit, allowing children as young as eight to assemble a device as sophisticated as the kind grown-ups use—complete with a flash and standard, 3-D and panoramic lenses—only cooler. Its color palette is inspired by M&Ms, a hand crank provides power even when there are no batteries and a transparent back panel shows the camera’s inner workings.”

With the BigShot, Nayar wants to not only empower children and encourage their creative vision, but also get them excited about science. Each building block of the camera is designed to teach a basic concept of physics: why light bends when it passes through a transparent object, how mechanical energy is converted into electrical energy, how a gear train works.

Watch Professor Shree Nayar talk about the purpose and development of the Bigshot camera project.

Nayar would like to roll out the camera, now in prototype form, along the lines of the One Laptop Per Child campaign: For each one sold at the full price of around $100, several would be donated to underprivileged schools in the United States and abroad. He will soon begin looking for a partner—a company or nonprofit—to help put Bigshot into production.

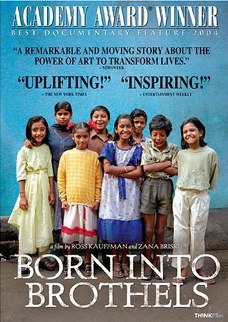

Interestingly, the initial inspiration for BigShot came from a documentary: Born into Brothels (85 mins, 2004), a film about the children of prostitutes in Sonagachi, Kolkata’s red light district. The widely acclaimed film, written and directed by Zana Briski and Ross Kauffman, won a string of accolades including the Academy Award for Documentary Feature made in 2004.

I saw that film during the AIDS Film Festival I helped organise in Bangkok in July 2004. In this film, the film maker, British photographer Zana Briski, gave 35 mm film cameras to eight children and watched as those cameras transformed their lives.

“The film reaffirmed something I’ve believed for a long time, which is that the camera, as a piece of technology, has a very special place in society,” says Nayar. “It allows us to express ourselves and to communicate with each other in a very powerful way.”

Watch an overview of Born into Brothels, featuring the film makers: