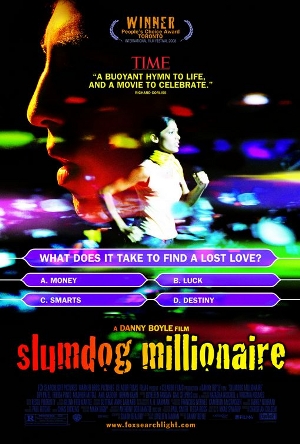

These words came to my mind as I watched the new Danny Boyle movie Slumdog Millionaire in New Delhi on its opening night on 23 January 2009. For two hours, it held me spellbound and transported me, alternately, to the rough world of Mumbai slums and the glitzy world of television quizzing in Bollywood.

It’s a feel-good, rags-to-riches story about Jamal Malik, an 18 year-old orphan from the slums of Mumbai who goes on to win a staggering 20 million Indian Rupees (a little over US$ 400,000) on India’s version of the popular TV game show Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? . The story, adapted from an award-winning novel Q&A(2005) by Indian diplomat Vikas Swarup, resonated strongly with me given my own, long-standing association with the overlapping worlds of quizzing and TV hosting.

As the story unfolds, we find out how and why Jamal – who has had little or no formal schooling and lacks ambition to win the quiz – got on the show: for a very personal reason. Through a series of amazing coincidences, well known in the movies that often ask us to suspend disbelief, the answer to each question he faces is deeply etched in his memory from his tumultuous past.

When the show breaks for the night, Jamal is only one question away from winning the show’s grand prize, which can make him a multi-millionaire. But the show’s organisers just can’t believe that an uneducated street kid (or a ‘slum dog’) has made it thus far on his own. So they call in the police.

As the police inspector says: “Doctors… Lawyers… never get past 60 thousand rupees. He’s on 6 million.” The question for everyone is: how does he do it?

Jamal is arrested on suspicion of cheating, and police torture him overnight to find out how. Desperate to prove his innocence, Jamal tells the story of his life in the slum where he and his brother Salim grew up, of their adventures together on the road, of vicious encounters with local gangs, and of Latika, the girl he loved and lost. Each chapter of his story reveals the key to the answer to one of the game show’s questions…

Watch the official movie trailer for Slumdog Millionaire:

Jamal returns the next evening – straight from police custody – to face the final question. The right answer would earn him 20 million; giving the wrong answer would lose all his winnings so far. By this time, his meteoric rise to the final question has made news headlines and tens of millions of TV viewers across India are watching the show and cheering for him. Among them is the young woman for whom Jamal got on the show in the first place…

The dramatic story ends on a happy note, in true Bollywood style, when boy meets his long-lost girl. One of its sub-plots offers insights into the high adrenalin world of quiz shows, which are now being played for high stakes.

The film uses the actual set of Kaun Banega Crorepati (KBC), the Indian version of the globally popular game show, Who Wants to be a Millionaire? which offers large cash prizes for correctly answering 15 (or in some countries, 12) consecutive multiple-choice questions of increasing difficulty. It represents the highly commercialised end of the quizzing world, which traditionally shunned cash rewards for performance. For example, the winner of BBC Mastermind receives nothing more than the coveted title.

I can’t remember exactly when I first took part in a general knowledge quiz — that is now buried too deep in the sediments of my memory. But I have been an active participant in the fascinating world of quizzing for at least three quarters of my 42 years, first as a quiz kid and then as a quiz master.

Slumdog Millionaire reinforces a point I have been making for years: not to equate knowledge with intelligence. Quizzes of every kind only test the general knowledge and quick recollection ability among participants — but not necessarily their intelligence. Measuring intelligence (that is, determining intelligence quotient, or IQ) is a specialised and complicated process. In any case, scientists acknowledge that such measurements are not always accurate because of cultural diversity and other variables. Although someone excelling in quiz would, in all likelihood, also have a high level of intelligence, quiz performance by itself is no measure of someone’s IQ.

Similarly, there is also no direct co-relation between the level of educational attainment and performance at general knowledge quizzes. While good quiz kids generally tend to be high achievers in their curriculum studies, that is not always so. I remember a London taxi driver once beating dozens of academics and professionals to become the overall winner in Brain of Britain, the BBC’s long-running radio quiz show. Apparently he used to read a great deal while waiting for hires.

Finally, I know of serious quiz enthusiasts who frown upon game shows like KBC as a dumbing down of the cerebral art. But there’s no denying that, by invoking popular culture, the new formats have hugely enhanced the audiences following quizzing on TV. For the true aficionados, there’s always Mastermind and other ‘pure’ forms of quizzing that remain above the fray of commerce. For the rest, there are shows that mix the quest for knowledge with the pursuit of happiness through material rewards.

Who’s afraid of the lure of 20 million Rupees?

An aside: I remember making the same point to assembled ITU, UNESCO and other UN worthies at the

An aside: I remember making the same point to assembled ITU, UNESCO and other UN worthies at the