“Can you help us to film a child’s leg being broken?”

In his long years of journalism in India, my friend Darryl D’Monte had faced all sorts of questions and situations. But this was one question that stunned and left him speechless for a while.

A visiting Canadian TV crew made this request in the 1970s, when Darryl was resident editor of The Times of

India. He was giving them some insights on the extent of poverty in his city of Bombay, since renamed as Mumbai. The crew had heard of the deliberate maiming of street children, before being employed as beggars. A disabled child would evoke more sympathy, increasing the daily collection for gangsters operating them from behind the scenes.

Darryl wasn’t willing to be associated with this ‘staging’. “Well, it’s going to happen anyway,” was the film crew’s cynical answer.

Now, fast forward 30 years to the present. At one point in the British-Indian movie Slumdog Millionaire, we see a young girl being blinded by a gangster who shelters and feeds a small army of children — all unleashed on Mumbai on a daily basis to tug at the heart strings of its teeming millions.

The film’s protagonist Jamal escapes the same fate by making a mad dash for freedom with his brother, Salim. But years later, they cross the gangster’s path again, with devastating results – for him.

Some Indians feel their country’s ugly underbelly has been magnified by locating and filming part of the story in the slums of Mumbai. But director Danny Boyle, who sees his film as a Dickensian tale, says he shot in real, gritty locations “to show the beauty and ugliness and sheer unpredictability” of the city.

Indian diplomat Vikas Swarup, who wrote the 2005 novel Q and A on which the movie is based, has a similar view. “This isn’t social critique,” he told The Guardian in an interview. “It’s a novel written by someone who uses what he finds to tell a story. I don’t have firsthand experience of betting on cricket or rape or murder. I don’t know if it’s true that there are beggar masters who blind children to make them more effective when they beg on the streets. It may be an urban myth, but it’s useful to my story.”

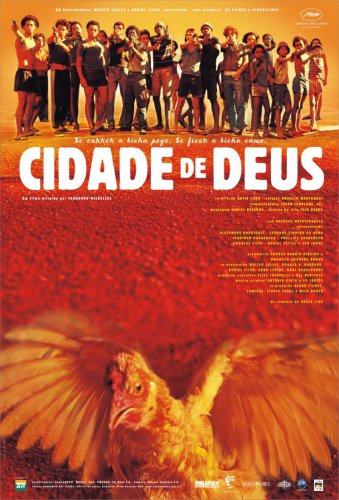

To me, Slumdog Millionaire feels like a cross between the acclaimed Brazilian slum movie City of God (Portuguese name: Cidade de Deus, 2002) and Quiz Show, the 1994 American historical drama film about TV quiz scandals in the 1950s.

City of God is a Brazilian crime drama film directed by Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund, released in its home country in 2002 and worldwide in 2003. It was adapted by Bráulio Mantovani from the 1997 novel of the same name written by Paulo Lins.

The film’s depiction of narcotic drug rings, hold-ups, street violence and police corruption may not have been what the upper middle class Brazilians wanted to showcase to the rest of the world, but the film’s stark if grisly authenticity resonated with movie audiences around the world. Most of the actors were residents of favelas (slums) of Rio de Janeiro, such as Vidigal and the Cidade de Deus itself. City of God became one of the highest-grossing foreign films released in the United States up to that time.

The makers of Slumdog Millionaire adopted a similar approach. Its co-director Loveleen Tandan says she likes to get as close to reality as possible. This drove her to the slums of East Bandra to look for young children who resembled the protagonists in the story.

As she recalled in a recent interview with Tehelka: “I was very keen to get real slum kids, which is why I convinced them (producers) to do one-third of the scenes in Hindi. I made a scratch tape with real street kids. The team was surprised that Hindi actually made it brighter and more alive.”

Indeed, Slumdog doesn’t feel like a ‘foreign film’ despite it having a fair number of English subtitles, which only enhance the overall cinematic experience.

But how realistic should films try to become, before the local realities are distorted or local sensibilities are affected? Where does documentary end and drama begin? These questions will continue to be debated across India and elsewhere while Slumdog enthralls millions on its first theatrical release.

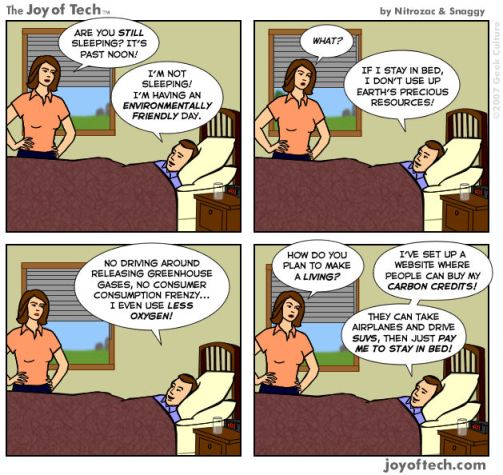

Feature film makers can exercise their creative license far more than factual film makers. I doubt if the creators of authentic, close-to-the-ground movies like City of God and Slumdog Millionaire set out with any specific social agenda. They are in the business of entertainment, and just happen to find plenty of drama in real life in places like urban slums. We might argue that in the right hands, dramatised movies can draw mass attention to development issues and challenges far more effectively than the often dull and dreary documentaries.

In a perceptive essay titled Shantytowns of the Mind, written in The Indian Express in early January 2009 before she saw the film, Kalpana flagged important concerns: “Slumdog Millionaire’s success raises some deeper questions. How do we depict poverty as writers, filmmakers, journalists? Is it fair to expect us all the time to give a full, balanced, sensitive portrayal? Or is it inevitable that we write, film, for our audiences? And if, as a byproduct, people are sensitized, so be it. Also, if they are annoyed, so be it. If we are considered exploitative, so be it.”

Kalpana speaks with authority, and not just because she lives in the megacity of Mumbai (population: 13 million and rising) which, she points out, is half made up of slums. In 2000, she wrote a book titled Rediscovering Dharavi: Stories from Asia’s Largest Slum. Far from being a cold, clinical analysis of facts, figures and trends, it’s a book about the extraordinary people who live there, “many of whom have defied fate and an unhelpful State to prosper through a mix of backbreaking work, some luck and a great deal of ingenuity”.

Kalpana ends her essays with these words: “In the end you realise as a writer, a journalist or a filmmaker, that the best you can do is to shine a torch, a searchlight, on an entrenched problem. But the solution will not be found merely by that illumination. For that, there are many more steps to be taken.

“Slumdog Millionaire has focused its lens on the children of India’s slums through a work of fiction. What we do to change their future is the non-fiction that has yet to be written.”

Read Shantytowns of the Mind by Kalpana Sharma, Indian Express, 14 January 2009