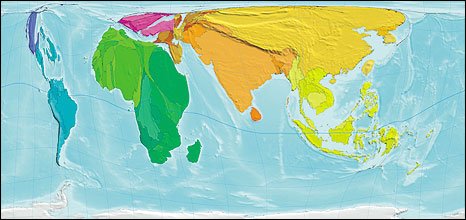

Take a close look at this map. What’s happened to our familiar world?

This is the map of human poverty — showing the proportion of poor people living in each country.

The size of each country/territory shows the overall level of poverty, quantified as the population of the territory multiplied by the Human Poverty Index. The index is used by the UNDP to measure the level of poverty in different territories. It attempts to capture all elements of poverty, such as life expectancy and adult literacy.

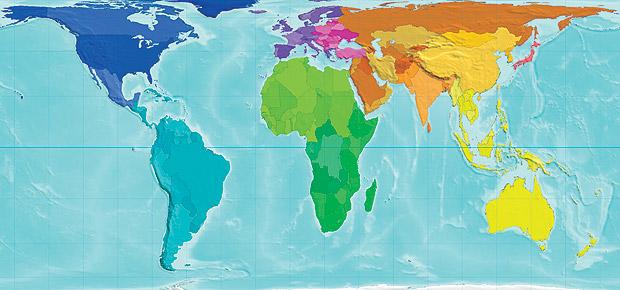

This map is from the recently released new book, Atlas of the Real World. It uses software to depict the nations of the world, not by their physical size, but by their demographic importance on a range of subjects.

This map is from the recently released new book, Atlas of the Real World. It uses software to depict the nations of the world, not by their physical size, but by their demographic importance on a range of subjects.

It carries maps constructed to represent data, such as population, migration and economics. But instead of a conventional map being coloured in different shades, for instance, the maps in this Atlas are differently sized. For instance, a country with twice as many people as another is shown twice the size; a country three times as rich as another is three times the size. And so on.

When depicted in this manner, a very different view of our real world emerges. The one on the distribution of poverty, shown above, reminds us something often overlooked: there are more poor people in Asia than anywhere else in the world.

It takes a map like this to drive home such a basic fact. In most discussions on international development or poverty reduction, it is Africa that dominates the agenda. Even those organisations and activists who claim to be evidence-based don’t always realise that when it comes to absolute numbers, and not just percentages, poverty and under-development affects far more Asians than Africans.

Atlas of the Real World, which I haven’t yet seen except through glimpses offered by The Telegraph (UK) and BBC Online, offers many such insights on what our topsy-turvey world is really like.

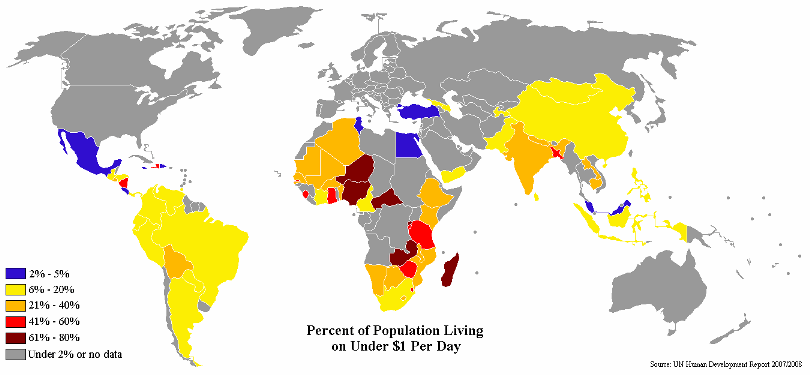

Their map of human poverty draws on the same data that this standard depiction does, in a map I found on Wikipedia sourcing the UN Human Development Report 2007/2008.

There are many ways of measuring income poverty, and experts don’t always agree on methods and outcome. But we will leave those technicalities to them. Global Issues is a good website that discusses these issues without too much jargon.

Accurately drawing a two-dimensional map of our spherical world has been a challenge for centuries. Today’s most widely used Mercator projection represents our usual view of the world – with north at the top and Europe at the centre. People in other parts of the world may not always agree with this view.

The Peters Projection World Map is one of the most stimulating, and controversial, images of the world. Introduced in the early 1970s, it was an attempt to correct many imbalances and distortions in the Mercator map.

An example: in the traditional Mercator map, Greenland and China look to be the same size but in reality, China is almost 4 times larger! Peters map shows the two countries in their relative sizes.

Atlas of the Real World also carries one map where the size of each territory represents exactly its land area in proportion to that of the others, giving a strikingly different perspective from the Mercator projection most commonly used. It is very similar to the Peters map of the world.

The UNDP has been producing its influential Human Development Report since 1990. As far as I can discern, the HDR always uses conventional (Mercator?) maps, depicting data using the standard colour-coding or gray tones. The one I have reproduced in this post is an example.

Indeed, the UN’s Cartographic Section seems to favour these.

When would the UNDP – and other members of the UN family – start using more innovative ways such as those used in Atlas of the Real World? How much more effective can the UN’s analysis be if they move out of the comfort zone of Mercator?

Instead, he drew from the practical, real life experiences of the

Instead, he drew from the practical, real life experiences of the