Can five unknown Norwegians achieve the worthy goal that has eluded so many leaders and activists – peace within and among nations of our world?

Well, if the individuals happen to be selectors of the world’s most prestigious prize – the Nobel Peace Prize – they stand a better chance than most people. The Norwegian Nobel Committee, appointed by the country’s parliament for six-year terms, may not be very well known beyond their country but their annual selection reverberates around the world and has changed the course of history in the past century.

But Professor Geir Lundestad, Director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute, says the Nobel Peace Prize cannot claim to have achieved peace on its own.

“It’s the laureates who work tirelessly and sometimes at great personal risk to pursue peace and harmony in their societies or throughout the world,” he told the international advisory council meeting of Fredskorpset, the Norwegian peace corp, held in Oslo on 4 – 5 September 2008. “With the Nobel Peace Prize, we try to recognise, honour and support the most deserving among them.”

Where high profile laureates are concerned, the prize becomes an additional accolade in their already well known credentials. But for those who are less known in the international media or outside their home countries, being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize is akin to being handed over a ‘loud speaker’ — it helps to amplify their causes, struggles and voices, he said.

In today’s media-saturated information society, the value of such an amplifier cannot be overestimated, says Lundestad, who also serves as Secretary to the Nobel Peace Prize selection committee. It allows laureates to rise above the cacophony and babble of the Global Village.

Every year in October, Lundestad makes one of the most eagerly awaited announcements to the world media: the winner of that year’s Nobel Peace Prize. He would typically give a 45 minute advance warning to the laureate – this is the famous ‘call from Oslo’ (and ‘call from Stockholm’ for laureates of other Nobel prizes).

Lundestad, who has held his position since 1990, has had interesting experiences in making this call. For example, the 1995 prize was equally divided between the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs and Englishman Joseph Rotblat, its founding secretary general, for their efforts to diminish the part played by nuclear arms in international politics. But when he received the call, Rotblat had insisted that it was some sort of mistake; the media had hyped the prospect of then British prime minister John Major winning the prize for his work on Northern Ireland peace process. He went for a long walk and wasn’t home when the world’s media beat a path to his door a short while later.

Such early warning to the laureate does not always happen, especially if the media keeps a vigil at the favourite contender’s home or office. When Al Gore and the UN-IPCC were jointly awarded the 2007 prize, Lundestad rang the New Delhi office of IPCC chairman Dr Rajendra Pachauri shortly before the decision was announced in Oslo. Pretending to be a Norwegian journalist, he asked Pachauri’s secretary whether any media representatives were present. Being told yes, he just hung up.

The Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded to 95 individuals and 20 organizations since it was established in 1901. During this time, the Norwegian Nobel Committee has tried to honour the will of Swedish engineer, chemist and inventor Alfred Nobel. Where the peace prize was concerned, he wrote that it should go “to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses”.

To decide who has done the most to promote peace is a highly political matter, and scarcely a matter of cool scholarly judgement, said Prof Lundestad, who is also one of Norway’s best known historians. He described the thorough selection process and the various checks and balances in place so that the prize does not become, even indirectly, an instrument of Norwegian foreign policy.

Notwithstanding these, the peace prize does not have a perfect record in whom it has selected as well as those it has failed to honour. The most glaring omission of all, he said, was Mahatma Gandhi.

Gandhi was nominated five times – in 1937, 1938, 1939, 1947 and, finally, a few days before he was assassinated in January 1948. The rules of the prize at the time allowed posthumous presentation, but the then committee decided not to (although UN secretary general Dag Hammarskjöld did receive the 1961 prize posthumously after he died in a plane crash). Gandhi’s omission has been publicly regretted by later members of the Nobel Committee; when the Dalai Lama was awarded the Peace Prize in 1989, the chairman of the committee said that this was “in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi”.

Read Nobel website’s essay: Mahatma Gandhi: The Missing Laureate

The prize does not have a very good track record in gender balance either. Only 12 of the 95 individual winners are women. Heroines of Peace: profiles of women winners (up to 1997)

And a few laureates may not have deserved to be so honoured – but Lundestad won’t name any for now (he likes his job and wants to keep it). Perhaps one day, after retirement, he might write a book where this particular insight could be shared.

Controversy has been a regular feature of the prize – both over its selections and exclusions. This is only to be expected when thousands of nominations are received every year, and given the high level political message the selection sends out to the world.

Despite its flaws, there is little argument that the Nobel Peace Prize is the most prestigious of all awards and prizes in the world. At Swedish Krona 10 million, or a little over 1.5 million US Dollars, it isn’t the most lavish prize – but much richer prizes lack the brand recognition this one has achieved over the decades. And it is the best known among over 100 peace prizes in the world.

In recent years, the committee has steadily expanded the scope of the prize to recognise the nexus between peace, human security and environmental degradation (Wangaari Mathaai in 2004; Al Gore and IPCC in 2007) and the link between poverty and peace (Mohammud Yunus, 2006).

The most important question, to many historians and scholars of peace, is the political and social impact of the Nobel Peace Prize. Lundestad is being too modest when he says that it’s the laureates, not the prize itself, that has achieved progress in various spheres ranging from nuclear disarmament and humanitarian intervention to safeguarding human rights and poverty reduction.

“We may have contributed — and that is quite enough,” he says. “We don’t claim to have ended the Cold War, or apartheid in South Africa.”

But the prize’s influence and catalytic effect are indisputable. When the 1983 prize was given to Polish trade union leader Lech Walesa, it triggered a whole series of events that eventually led to the crumbling of the Iron Curtain, collapse of the Berlin Wall and the eventual disintegration of the once mighty Soviet Union. The process culminated when Mikhail Gorbachev became the 1990 laureate.

Read Nobel Peace Prize: Revelations from the Soviet Past

In another example, over the years there have been four South African laureates – Albert Lutuli (1960), Bishop Desmond Tutu (1984), Nelson Mandela and F W de Klerk (sharing 1993 prize). Lundestad says: “But we would never claim that the prize was a major factor in ending apartheid in South Africa. The prize was part of the wider international support that built up and sustained pressure on the white minority government. In some respects, the 1960 prize to Lutuli may have been the most significant – for it triggered a process that culminated in the early 1990s.”

He acknowledges, however, that in hot spots like Burma, East Timor and South Africa, the Nobel Peace Prize has enhanced the profile of key political activists and helped maintain the international community’s and media’s interest in these long drawn struggles.

And as Lundestad and the Nobel Peace Prize Committee of five unknown Norwegians know all too well, there is much unfinished business in our troubled and quarrelsome world seeking an elusive peace.

Read Geir Lundestad’s 2001 essay on the first century of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Read his 1999 essay ‘Reflections on the Nobel Peace Prize’

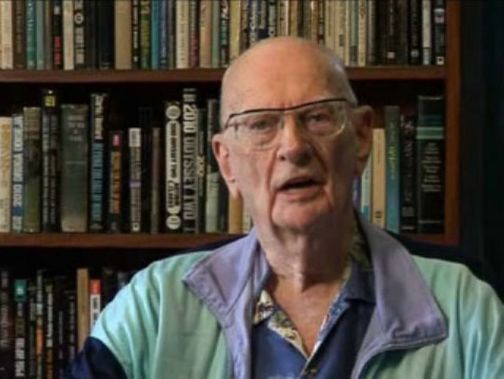

Watch a 2005 interview by University of California television, where host Harry Kreisler talks with Geir Lundestad. They discuss the Nobel Peace Prize, its history, impact and the controversy surrounding some of the awardees (December 2005):

Instead, he drew from the practical, real life experiences of the

Instead, he drew from the practical, real life experiences of the