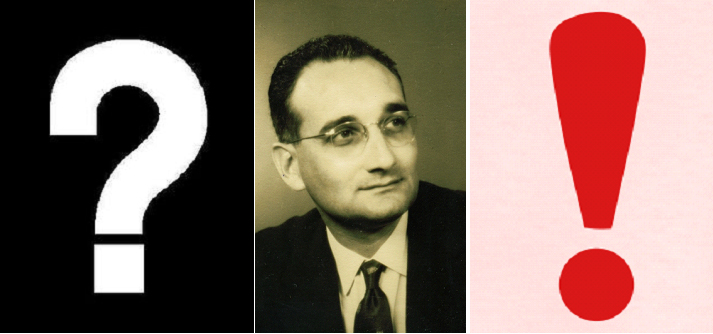

In this column, which appears in Ravaya newspaper on 30 October 2011, I pay tribute to the late film and TV professional Titus Thotawatte. I recall how he founded and headed the effort to ‘localise’ foreign-produced programmes during the formative years of Sri Lanka’s national TV, Rupavahini, launched in 1982. In particular, I describe how Titus resisted attempts by intellectuals and civil servants to turn the new medium into a dull and dreary lecture room, and insisted on retaining quality entertainment as national TV’s core value.

See also my English tribute Titus Thotawatte (1929 – 2011): The Final Cut. However, this is a different take; I NEVER translate even my own writing.

ටයිටස් තොටවත්ත සූරීන් අඩ සියවසක් පුරා රූප, නාද හා වචනවලින් හපන්කම් රැසක් කළා. සිංහල සිනමාවේ තාකෂණික වශයෙන් අති දකෂ සංස්කාරකයකු හා චිත්රපට අධ්යකෂවරයකු හැටියට ඔහු කළ නිර්මාණ වඩාත් මතක ඇත්තේ අපේ දෙමවුපියන්ගේ පරම්පරාවට. ලංකාවේ පළමුවන ටෙලිවිෂන් පරම්පරාවට අයිති මා වැනි අයට තොටවත්තයන් සමීප වූයේ ටෙලිවිෂන් මාධ්යයෙන් නව මං සොයා යාම නිසයි. මේ නිසා ඇතැම් දෙනකුට ටයි මහත්තයා වූ ඔහු, මගේ පරපුරේ අයට ‘ටයි මාමා’. ටෙලිවිෂන් තිරය මතුපිට මෙන් ම එය පිටුපසත් මෙතරම් විවිධ දස්කම් පෙන්වූවන් අපේ ටෙලිවිෂන් ඉතිහාසයේ දුර්ලභයි. ටයි මාමාගේ ටෙලිවිෂන් දායාදය ගැන ටිකක් කථා කරන්නේ ඒ නිසයි.

ලෝකයේ ඕනෑ ම සංස්කෘතියක ඇති හොඳ දෙයක් සොයා ගෙන එය අපට දිරවා ගත හැකි, අපට ගැලපෙන ආකාරයෙන් ප්රතිනිර්මාණය කිරීමට දේශීයකරණය කියා කියනවා. මා වඩා කැමති යෙදුම ‘අපේකරණයයි’. අපේ ටයි මාමා අපේකරණයට ගජ හපනෙක්!

1982 වසරේ රූපවාහිනී සංස්ථාව අරඹා මාස කිහිපයක් ඇතුළත එයට එක් වූ ටයි මාමා, ලංකාවට නැවුම් හා ආගන්තුක වූ මේ නව මාධ්යය අපේකරණයට විවිධ අත්හදා බැලීම් කළා. පුරෝගාමී ටෙලි නාට්ය කිහිපයක් මෙන් ම වාර්තා වැඩසටහන් ගණනාවක් ද ඒ අතර තිබුණත් අපට වඩාත් ම සිහිපත් වන්නේ ඔහු කළ හඩ කැවීම් හා උපශීර්ෂ යෙදීම් ගැනයි.

රූපවාහිනී සංස්ථාවේ හඩ කැවීම් හා උපශීර්ෂ සේවාව ඇරඹුවේ 1984දී. එයට දිගු කල් දැක්මක් හා තාකෂණික අඩිතාලමක් ලබා දුන්නේ ටයි මාමායි. අළුත ඇරැඹුණු නව මාධ්යයෙන් විකාශය කරන්නට අවශ්ය තරම් දේශීය වැඩසටහන් නොතිබුණු, එමෙන්ම දේශීය නිර්මාණ එක්වර විශාල පරිමානයෙන් කරන්නට නොහැකි වුණු පසුබිමක් තුළ තෝරා ගත් විදෙස් වැඩසටහන් මෙරට භාෂාවලට පෙරළා ගැනීම ටෙලිවිෂන් මුල් දශකයේ එක් උපක්රමයක් වුණා.

මේ අනුව සම්භාව්ය මට්ටමේ විදෙස් වාර්තා චිත්රපට, නාට්ය හා කාටුන් කථා සිංහලයට හඩ කැවීම හෝ උපශීර්ෂ යෙදීම ටයි මාමාගේ නායකත්වයෙන් ඇරඹුණා. මුල් කාලයේ තාකෂණික පහසුකම් සීමිත වුණත් නිර්මාණශීලීව ඒ අඩුපාඩුකම් මකා ගෙන ඔවුන් ඉතා වෙහෙස මහන්සිව වැඩ කළා. විදෙස් කෘතීන්ගේ කථා රසය නොනසා, අපේ බස ද නොමරා හොඳ හඩ කැවීම් හා උපශීර්ෂ යෙදීම් කරන සැටි පෙන්වා දුන්නා. මේ ගැන මනා විස්තරයක් නුවන් නයනජිත් කුමාර 2009 දී ලියූ ‘සොඳුරු අදියුරු සකසුවාණෝ’ නමැති තොටවත්ත අපදානයේ හතරවැනි පරිච්ඡේදයේ හමු වනවා.

එහි එක් තැනෙක ටයි මාමා ආවර්ජනය කළ පරිදි: “හැම ප්රේකෂකයකු විසින් ම රස විඳිය යුතු ඉතා උසස් ගණයේ ඉංග්රීසි වැඩසටහන් බොහොමයක් තිඛෙන වග වැටහුණේ රූපවාහිනියට බැඳුණාට පසුවයි. ඒත් අපේ රටේ කීයෙන් කී දෙනාට ද ඉංග්රීසි භාෂාව තේරුම් ගන්නට පුළුවන්. උපසිරැසි යොදා හෝ හකවා හෝ එම චිත්රපට වැඩසටහන් විකාශය කිරීමට මා උනන්දු වුණේ ඒ නිසා…ඒවාහි අපට ඉගෙන ගත හැකි ආදර්ශවත් දෑ කොතෙකුත් තිඛෙනවා. කාටුන් වැඩසටහන්වලට පුංචි එවුන් පමණක් නොවෙයි, වැඩිහිටි අපිත් කැමැතියි. මා උත්සාහ කරන්නේ ඒ හඩ කැවීම් වුණත් අපේ දේශීයත්වයට හා රුචිකත්වයට අනුකූලව සකස් කරන්නයි. එහිදී මා යොදා ගන්නා දෙබස් හා උපසිරස්තල අපේ සංස්කෘතියට සමීප ව්යවහාරයේ පවතින දේයි.”

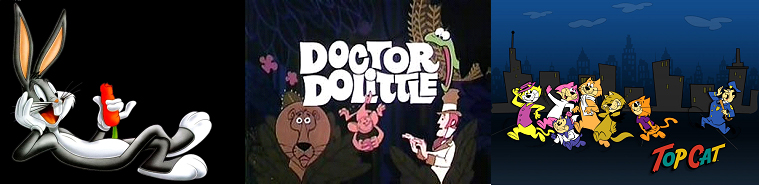

හාන්ස් ක්රිස්ටියන් ඇන්ඩර්සන්ගේ කථා ඇසුරෙන් නිර්මිත ඉංග්රීසි වැඩසටහනක් ‘අහල පහල’ හා ‘ලොකු බාස් – පොඩි බාස්’ නමින් සිංහලට හ~ කවා මුල් වරට විකාශය කළේ 1985 පෙබරවාරි 15 වනදා. එතැනින් පටන් ගත් විදෙස් වැඩසටහන් අපේකරණය විවිධාකාර වූත් විචිත්ර වූත් මුල් කෘතීන් රාශියක් මෙරට ටෙලිවිෂන් ප්රේකෂයන්ට දායාද කළා. මේ අතරින් ඉතා ජනාදරයට පත් වූයේ ලෝක ප්රකට කාටුන් වැඩසටහන්. (ටයි මාමාගේ යෙදුම වූයේ ‘ඇසිදිසි සැකිලි රූ’.)

උදාහරණයකට ‘දොස්තර හොඳ හිත’ කථා මාලාව ගනිමු. එහි මුල් කෘතිය Dr Dolittle නම් ලෝක ප්රකට ළමා කථාවයි. හියු ලොෆ්ටිං (Hugh Lofting) නම් බ්රිතාන්ය ලේඛකයා 1920 සිට 1952 කාලය තුළ දොස්තර ජෝන් ඩූලිට්ල් චරිතය වටා ගෙතුණු කථා පොත් 12ක් ලියා පළ කළා. සතුන්ට කථා කළ හැකි, කරුණාවන්ත හා උපක්රමශීලි වෛද්යවරයකු වන ඔහු මිනිසුන් හා සතුන්ගෙන් සැදුම් ලත් මිතුරු පිරිසක් සමඟ නැවකින් ගමන් කරනවා. ඔහුට එදිරිවන මුහුදු කොල්ලකරුවන් පිරිසක් — ‘දිය රකුස්’ සහ ඔහුගේ සගයෝ — සිටිනවා. මේ පොත් පාදක කර ගෙන වෘතාන්ත චිත්රපට ගණනාවක්, වේදිකා නාට්ය හා රේඩියෝ වැඩසටහන් නිපදවී තිඛෙනවා. 1970-71 කාලයේ අමෙරිකාවේ NBC ටෙලිවිෂන් නාලිකාව විකාශය කළ Doctor Dolittle නම් කාටුන් කථා මාලාව තමයි ටයි මාමා ඇතුළු පිරිස දොස්තර හොඳ හිත නමින් සිංහලට හඩ කැවූයේ.

බ්රිතාන්ය ලේඛකයකුගේ කථා, අමෙරිකානු ශිල්පීන් අතින් ඇසිදිසි කථා බවට පත්ව මෙහි ආ විට එය අපේ කථාවක් කිරීමේ අභියෝගයට ටයි මාමා සාර්ථකව මුහුණ දුන්නා. එහිදී ප්රේමකීර්ති ද අල්විස් ලියූ රසවත් හා හරවත් ගීත අපේකරණය වඩාත් ඔප් නැංවුවා. කථා රසය රැක ගන්නා අතර ම සිංහලට ආවේනික වචන, යෙදුම්, ප්රස්තාපිරුළු හා ආප්තෝපදේශවලින් දෙබස් උද්දීපනය කළා.

මෙය ලෙහෙසි කාරියක් නොවෙයි. විදෙස් කාටූනයක් හඩ කවද්දී එහි පින්තූරවල වෙනසක් කරන්නේ නැහැ. මුල් කෘතියේ ධාවන වේගය හා සමස්ත ධාවන කාලය එලෙස ම පවත්වා ගත යුතුයි. එහිදි ඉංග්රීසි දෙබස්වලට ආදේශ කරන සිංහල දෙබස් එම තත්පර ගණන තුළ ම කියැවී හමාර විය යුතුයි. මේ තුලනය පවත්වා ගන්නට බස හොඳින් හැසිර වීම මෙන් ම විනෝදාස්වාදය නොනැසෙන ලෙස අපේකරණය කිරීමත් අත්යවශ්යයි.

ටයි මාමා සාර්ථක ලෙස අපේකරණය කළ කාටුන් කථා මාලා රැසක් තිඛෙනවා. 1944දී වෝනර් බ්රදර්ස් සමාගම නිපදවීම පටන් ගත්, දශක ගණනක් තිස්සේ ලෝ පුරා ප්රේකෂකයන් කුල්මත් කළ Bugs Bunny කාටුන් චරිතයට ඔහු ‘හා හා හරි හාවා’ නම දුන්නා. එයට ආභාෂය ලැබුවේ කුමාරතුංග මුනිදාස සූරීන්ගේ ‘හාවාගේ වග’ ළමා කවි පෙළින්. 1961-62 කාලයේ මුල් වරට අමෙරිකාවේ විකාශය වූ, හැනා-බාබරා කාටුන් සමාගමේ නිර්මාණයක් වූ Top Cat කථා මාලාව, ටයි මාමා සහ පිරිස ‘පිස්සු පූසා’ බවට පත් කළා. මෙබඳු කථාවල අපේකරණය කෙතරම් සූකෂම ලෙස සිදු වූවා ද කිවහොත් ඒවා විදෙස් කෘතීන්ගේ හ~ කැවීම් බව බොහෝ ප්රේකෂයන්ට දැනුනේත් නැති තරම්.

ටයි මාමා අපේකරණය කළේ බටහිර රටවල නිෂ්පාදිත කාටූන් පමණක් නොවෙයි. ලෝකයේ විවිධ රටවලින් ලැබුණු උසස් ටෙලිවිෂන් නිර්මාණ සිංහල ප්රේකෂකයන්ට ප්රතිනිර්මාණය කළා. මේ තොරතුරු නුවන් නයනජිත් කුමාරගේ පොතෙහි අග ලැයිස්තුගත කර තිඛෙනවා. රොබින් හුඩ් හා ටාසන් වැනි ත්රාසජනක කථා, මනුතාපය හා සිටුවර මොන්ත ක්රිස්තෝ වැනි විශ්ව සාහිත්යයේ සම්භාව්ය කථා, මල්ගුඩි දවසැ, ඔෂින් වැනි පෙරදිග කථා ආදිය එයට ඇතුළත්.

මෙසේ අපේකරණයට පත් කළ විදෙස් නිර්මාණවලට අමතරව ස්වතන්ත්ර ටෙලි නිර්මාණ රැසකට ද ටයි මාමා මුල් වූ බව සඳහන් කළ යුතුයි. එමෙන්ම ටෙලිවිෂන් සාමූහික ක්රියාදාමයක් නිසා ටයි මාමා නඩේ ගුරා ලෙස හපන්කම් කළේ දැඩි කැපවීමක් තිබූ, කුසලතාපූර්ණ ගෝල පිරිසක් සමඟ බවත් සිහිපත් කරන්න ඕනෑ. ප්රධාන ගෝලයා වූ අතුල රන්සිරිලාල් අදටත් ඒ මෙඟහි යනවා.

ටයි මාමාගේ සිනමා හා ටෙලිවිෂන් හපන්කම් ගැන ඇගැයීම් පසුගිය දින කිහිපය පුරා අපට අසන්නට ලැබුණා. මා ඔහු දකින්නේ අඩ සියවසක් පුරා පාලම් සමූහයක් තැනූ දැවැන්තයකු හැටියටයි. පාලමක් කරන්නේ වෙන් වූ දෙපසක් යා කිරීමයි. ටයි මාමා කිසි දිනෙක දූපත් මානසිකත්වයකට කොටු වුනේ නැහැ. ඔහු පෙරදිග හා අපරදිග හැම තැනින්ම හොඳ දේ සොයා ගෙන, ඒ නිර්මාණ අපේ ප්රේකෂකයන්ට ග්රහණය කළ හැකි ලෙස අපේකරණය කළා. එමෙන්ම සිනමාව හා ටෙලිවිෂන් මාධ්යය අතර හැම රටක ම පාහේ මතුවන තරගකාරී ආතතිය වෙනුවට මාධ්ය දෙකට එකිනෙකින් පෝෂණය විය හැකි අන්දමේ සබඳතාවන් ඇති කළා. වැඩිහිටියන් හා ළමයින් වශයෙන් ප්රේකෂකයන් ඛෙදා වෙන් කිරීමේ පටු මානසිකත්වය වෙනුවට අප කාටත් එක සේ රසවිඳිය හැකි ඇසිදිසි නිර්මාණ කළ හැකි බව අපේකරණය කළ වැඩසටහන් මෙන් ම ස්වතන්ත්ර වැඩසටහන් හරහා ද ඔප්පු කළා. ඔහුගේ පරම්පරාව හා මගේ පරම්පරාව අතර පරතරය පියවන්නත් ටයි මාමා දායක වුණා.

ටයි මාමා පාදා දුන් මෙඟහි ඉදිරියට ගිය දකෂයකු වූ පාලිත ලකෂ්මන් ද සිල්වා ගැන කථා කරමින් (2011 ජූනි 26 වනදා) මා කීවේ ටෙලිවිෂන් මාධ්යයේ අධ්යාපනික විභවය මුල් යුගයේ මෙරට ඒ මාධ්යය හැසිර වූ අය ඉතා පටු ලෙසින් විග්රහ කළ බවයි. ඒ අයගේ තර්කය වුණේ හරවත් දේ රසවත්ව කීමට බැරි බවයි. ඔවුන්ගේ පණ්ඩිතකම වෙනුවට ටයි මාමා අපට ලබා දුන්නේ හාස්යය, උපහාසය, රසාස්වාදය මනා සේ මුසු කළ එහෙත් හරවත් ටෙලිවිෂන් නිර්මාණයි. උවමනාවට වඩා ශාස්ත්රීය, ගාම්භීර හා ‘ප්රබුද්ධ’ විදියට නව මාධ්යය ගාල් කරන්නට උත්සාහ කළ සරසවි ඇදුරන්ට හා සිවිල් සේවකයන්ට ටයි මාමාගෙන් වැදුණේ අතුල් පහරක්.

උදාහරණයකට සිංහල ජනවහරේ හමු වන ‘උඹ’ හා ‘මූ’ වැනි වචන ළමා ළපටින් නරඹන ටෙලිවිෂන් කථාවලට උචිතදැයි සමහර සංස්කෘතික බහිරවයන් ටයි මාමා සමඟ තර්ක කර තිඛෙනවා. ටෙලිවිෂන් එකෙන් එබඳු වචන ඇසුවත් නැතත් සැබෑ ලෝකයේ එබඳු යෙදුම් එමට භාවිත වන බව ටයි මාමාගේ මතය වුණා. මෙසේ දැඩි ස්ථාවරයෙන් සිටීමට ඔහුට හැකි වුණේ ඇසිදිසි මාධ්ය ගැන මෙන්ම සිංහල බස ගැනත් බොහෝ සේ ඇසූ පිරූ කෙනකු නිසායි.

ඔහු කළ ලොකු ම සංස්කෘතික විප්ලවය නම් ළදරු රූපවාහිනී සංස්ථාවේ වැඩසටහන් පෙළගැස්ම අනවශ්ය ලෙසින් ‘පණ්ඩිත’ වන්නට ඉඩ නොදී, එයට සැහැල්ලූ, සිනහබර ශෛලියක් එකතු කිරීමයි. කට වහර හා ජන විඥානය මුල් කර ගත් ටයි මාමාගේ කතන්දර කීමේ කලාව නිසා රූපවාහිනිය යන්තම් බේරුණා. එසේ නැත්නම් සැළලිහිනියා පැස්බරකු වීමේ සැබෑ අවදානමක් පැවතුණා.

ලොව හැම තැනෙක ම බහුතරයක් දෙනා ටෙලිවිෂන් බලන්නේ රටේ ලෝකයේ අළුත් තොරතුරු (ප්රවෘත්ති) දැන ගන්නට හා සරල වින්දනයක් ලබන්නට. ටෙලිවිෂනය හරහා අධ්යාපනික හා සාංස්කෘතික වශයෙන් හරවත් දේ කළ හැකි වුවත් එය හීන් සීරුවේ කළ යුතු වැඩක්. හරියට ඛෙහෙත් පෙතිවලට පිටතින් සීනි ආලේප ගල්වනවා වගෙයි. එසේ නැතිව තිත්ත ඛෙහෙත් අමු අමුවේ දෙන්නට ගියොත් වැඩි දෙනෙකු කරන්නේ චැනලය මාරු කිරීමයි.

ටෙලිවිෂන් මාධ්යයේ නියම ‘ලොක්කා’ දුරස්ථ පාලකය අතැZති ප්රේකෂකයා මිස නාලිකා ප්රධානීන්, වැඩසටහන් පාලකයන් හෝ නිෂ්පාදකයන් නොවෙයි. නාලිකා දෙකක් පමණක් පැවති 1980 දශකයේ දී වුවත් මේ සත්යය හොඳාකාර වටහා ගත් ටයි මාමා, අප හිනස්සන අතරේ අපට නොදැනී ම හොඳ දේ ඛෙදන ක්රමවේදයක් ප්රගුණ කළා. ටයි පාරේ ගියොත් ටෙලිවිෂන් කලාවට වරදින්නට බැහැ!

විශේෂ ස්තුතිය: නුවන් නයනජිත් කුමාර