I spent a good part of my last week (9 – 13 December 2007, both days inclusive) in the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur participating in the Third Global Knowledge Conference or GK3.

GK3 was organised by a network called the Global Knowledge Partnership, as a platform for those interested in using information and communications technologies (ICTs) for the greater good – to solve real world problems of poverty, under-development, illiteracy and various other disparities that afflict our world.

Those within the GKP call it ICT for Development, abbreviated as ICT4D. I prefer the more catchy phrase ‘Geek2Meek’ (or using geeks’ tools/toys to serve the needs of the meek).

In the spirit of spawning endless acronyms and abbreviations that contribute to the Alphabet Soup, I will compress this as G2M.

GK3 was meant to showcase the best of G2M products, practices and processes in every area of human endeavour — education, health, natural resource management, poverty reduction, empowering youth and women, promoting enterprise, etc.

After spending a good deal of my time and energy sampling many of GK3’s offerings, my cumulative impression was: there was a lot of geek for sure, but very little of the meek.

And the nexus between geek (tools) and meek (needs) was hopelessly lost in the incredible volume of hype, PR and spin generated by the platform organisers. What a missed opportunity it was for everyone!

To be fair, GK3 was not a single conference, but a whole platform of events sharing the large physical space of the KL Convention Centre and spread through the week of 9 to 13 December 2007. During that time and using that space, various groups organised diverse events and activities — ranging from the usual talk sessions and workshops to training, exhibitions, quiz shows, a TV debate and a documentary film festival. There were also several social events that provided many hours networking among individuals and organisations.

Event platforms like GK3 mean very different things to different people. Some turn up mainly to show and tell (or share) what they are doing. Some attend simply to find out what’s going on. Others look for markets, partners or opportunities. With some planning and work, most participants get to take away something in the end.

All this certainly happened during GK3 to one extent or another. It brought together hundreds of people from all over the world who share an interest in G2M — according to official figures, a total of 1,766 registered participants from 135 countries, comprising 19% from public sector, 21% from private sector, 29% from civil society, 20% from international organisations, 5% from media and 6% from academia. Among them, 82% of participants were from developing countries. And half of all participants were from Asia, which was not surprising given their easier access to KL.

These participants — most of them eager, energetic and creative individuals — talked and mixed in a myriad combinations around the overall platform theme: how the threads of emerging people, markets and technologies will intertwine to deliver the future. There was discussion, debate, sharing and networking.

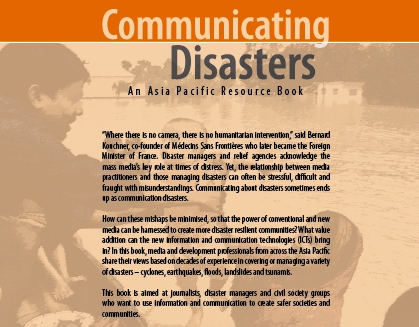

I myself did all of this. I attended part of the 3rd World Electronic Media Forum, joined the GKP’s 10th birthday celebration, sat through some plenary and parallel sessions and moderated two sessions myself. Some TVE Asia Pacific documentary films that I had scripted or directed were screened at the i4d film festival, a key side event. The week also saw the release of two Asian regional books that I was involved in creating (one I co-edited, and the other I wrote a chapter for).

But being the professional skeptic that I am, I don’t buy the GK3 secretariat’s post-event claim that “An overwhelming number of participants indicated that GK3 is the only event of its kind, is absolutely critical and worthwhile.” I have no doubt that a statistically higher number of people made nice and kind remarks about the week’s offerings, as many such people are wont to, especially if their participation was supported by travel scholarships. (I would be interested to know how many of the 1,700 people came on their own steam, as I did.)

In fact, style (and hype) over substance characterised the entire GK3 platform — the hype had actually started months before the event, with all registered participants being bombarded by endless promotional emails that I found simply intolerable. (And no, the organisers didn’t offer us the option of unsubscribing.) So much time, energy and donor funds were spent – nay, squandered – on dressing it up and inflating everything to the point of losing all credibility. If anyone was laughing all the way to their banks after GK3, it must be the assorted spin doctors!

As I have written and spoken (for example in an op ed article in i4d magazine, June 2006), the gulf between the (expensive) hype and reality in ICT circles can be wide and shocking. What is worth investigating is the development effectiveness of this whole platform, and the value for money it delivered.

Take, for example, an email circular sent out by the GK3 organisers days after the platform ended. Under ‘key initial findings’, they list the following for emerging technologies, the area that interests me the most (verbatim reproduction here):

Four future-oriented outlook involving technologies were highlighted – media, cybersecurity, low cost devices, and green technologies.

* Increased convergence of different media allows single broadcasting (one to many) to be complemented by social broadcasting (many to many), and in turn increases interactivity in the exchange of information.

* Cybersecurity, cybercrimes and cyberwaste are becoming real dangers which deserve special attention.

* More new low cost devices are needed to facilitate affordable access to information, knowledge, communication and new forms of learning.

* Demand for innovative green technologies is welcomed and growing.

I don’t see how any of this can be labelled as ‘findings’ — these are not even articulate expressions of already known trends, conditions or challenges. Is this how the ‘Event of the Future’ going to be recorded for posterity? Surely, GK3 achieved more than this – probably below the radar of its spin doctors?

GK3 to me was more evidence of the disturbing and very unhealthy rise of spin in international development circles, where both development organisations and development donors are increasingly investing in propagandistic, narcissistic communications products and processes. While publicity in small doses does little harm, it is definitely toxic in the large volume doses that are being peddled whether in relation to MDGs or humanitarian assistance or, as with GK3, in relation to Geek2Meek. Full-page, full-colour paid advertisements in the International Herald Tribune don’t come cheap — but they come at the expense of the poor and marginalised.

I was also struck by how web 1.0 the GK3 organising effort was — all official statements, images and communication products (and even social events) were so carefully crafted, orchestrated, controlled. Whatever spontaneous action came not from the Big Brotherly organisers but from some free-spirited participants who seized the opportunity to express or experiment. The defining characteristics of web 2.0 – of being somewhat anarchic, highly participatory and interactive – were not the hallmarks of GK3. Again, a missed opportunity.

Then there was the ridiculously named Moooooooooooooo – sorry, it was actually MoO, an abbreviation for ‘Marketplace of Opportunities’, which GK3 was supposed to create or inspire for all those engaged in Geek2Meek work.

The MoO turned out to be just another exhibition where two or three dozen organisations put up their ware to show and tell (and a few did brag and sing, but that’s allowed at places like this). Strangely for an ICT gathering, there was so much paper floating around — posters, leaflets, booklets, books, postcards, you name it! And very few CDs, DVDs and electronic formats being distributed.

Oct 2007 Blog post: Say Moooooooooo – Mixing grassroots and iCT in KL

In the last hour of the final day, I walked around the MoO (I must admit I was half curious to see if the cows have come home!). I was stunned by the massive volumes of mixed up paper lying around everywhere. The week’s events were drawing to an end, and it was unlikely there would be too many more takers for all this paper. My colleague Manori captured on her mobile phone this image of an exasperated me surrounded by mountains of paper.

The MoO exhibitors were not alone in their profligacy and wastefulness – the GK3 secretariat easily wins the prize for producing the greatest volume of glossy, expensive paper-based promotional material for at least a year preceding the event. These were often sent in multiple copies to heaven knows how many thousands of people all over the planet.

All this happened in a year (2007) when scientific confirmation of global climate change prompted governments, industry and civil society to realise that business as usual cannot continue, and more thrifty ways to consume energy and resources must be adopted. Ironically, GK3 was largely ignored by the world’s news media who focused much more attention on the UN Climate Change conference underway in neighbouring Indonesia’s Bali island.

I have commented separately on the missing link between KL and Bali. It is highly questionable what value-for-money benefit an ICT event like GK3 could derive from the abundance of paper-based materials produced to promote it. It’s revealing that the GKP’s oft-repeated claims of attracting 2,000 participants to GK3 were under-achieved despite excessive promotion.

Writing in October 2007, I said: “An informed little bird saysGK3 has milked development donors well and truly for this 3-day extravaganza. I hope someone will calculate the cost of development aid dollars per ‘Mooo’…”

Well, now is the time to ask those difficult questions. The donor agencies of several developed countries — and from Canada and Switzerland in particular — invested heavily in the GK3 extravaganza. These are public funds collected through taxes, given in trust to these agencies for rational and prudent spending. And it’s fair to say that most of this official development assistance (ODA) money is given with the noble aim of reducing poverty, suffering and socio-economic disparities in the majority world.

The GK3 organisers — that is, the GKP Secretariat — often talk in lofty terms about good governance, extolling the virtues of accountability and transparency. Here’s your chance to practise what you preach to the governments and corporations of the world: disclose publicly how much in total was collected for GK3 (from development donors, corporate sponsors, hefty registration fees), and how this money was spent. In sufficient detail, please!

We will then decide for ourselves whether GK3 provided value for money in the truest sense of that concept, and assess if GK3 was ‘absolutely critical and worthwhile’ as the organisers so eagerly claim.

It’s easy for like-minded people to become buddies and get cosy in international development networks. It’s also common to engage in self congratulatory talk and mutual back-slapping at and after gatherings like GK3. But too much manufactured (spun?) consensus and applause can blind our collective vision and lead us astray.

If we genuinely want to engage in Geek2Meek (or, ICT4D), we have to keep repeating the vital questions: what is the value addition that ICTs bring to the development process, and what is the value addition that mega-events like GK3 provide for turning geek tools to serve the meek? Answers must be honest, evidence-based and open to discussion (and dissension, if need be).

In not sharing the euphoria of GK3 organisers, I probably sound like that little boy who dared to point out that the mighty emperor had no clothes. If nobody talks these inconvenient truths and asks some uncomfortable questions, we would be going round and round in our cosy little grooves till the cows come home.

Did someone say Mooooooooooooo?

Read my November 2005 op ed essay written just after WSIS II: Waiting for pilots to land in Tunis

From KL to Bali: Why were ICT and climate change debates worlds apart?

In his new book, aptly titled Plunder, Danny offers an in-depth investigation into the decline of the economy that’s causing millions to lose jobs and face foreclosures and across-the-board price hikes.

In his new book, aptly titled Plunder, Danny offers an in-depth investigation into the decline of the economy that’s causing millions to lose jobs and face foreclosures and across-the-board price hikes.