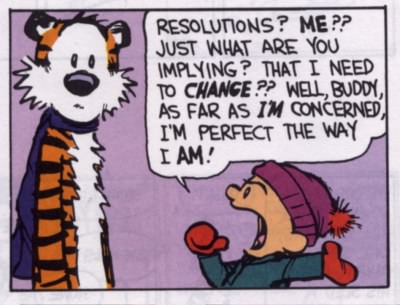

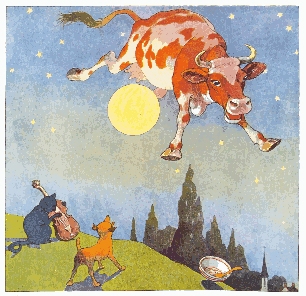

Sometime ago, when I gave a talk at the Sri Lanka Rationnalists’ Association, a member of my audience asked if parents should be banned from reading fairy tales to their children. His argued that children should be raised on reality and not fantasy. I was talking about science fiction and their social relevance, and I answered: there is absolutely no harm in fairy tales as they nurture in our young minds those vital qualities of imagination and sense of wonder. I quoted C S Lewis as saying that the only people really against escapism were…jailers!

These days, not all children’s stories are fairy tales and some of them actually carry very down-to-earth messages either overtly or covertly. Members of that largest club in the world – Parenthood – keep discovering new depths and insights in some children’s stories.

On 30 January, as people power struggles were unfolding in Tunisia and Egypt, I wrote a blog post titled Wanted: More courageous little ‘Mack’s to unsettle Yertle Kings of our times!. I related how, while following the developments on the web, I have been re-reading my Dr Seuss. In particular, the delightfully inspiring tale of Yertle the Turtle King. To me, that is the perfect example of People Power in action — cleverly disguised as children’s verse!

Turns out another parent on the opposite side of the planet had a similar insight, but from an even older children’s story written in Russia! Philip Shishkin has shared his experience in the latest issue of Newsweek.

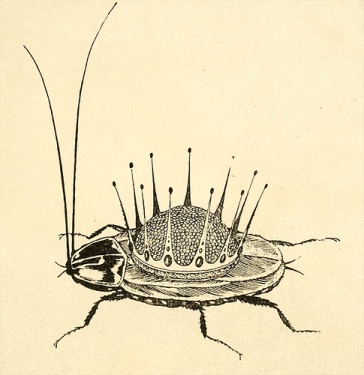

Tarankanische, or ‘The Terrible Cockroach’ (also translated as ‘The Giant Cockroach’) is a children’s story written by the Russian author Kornei Chukovsky (1882-1969). The first edition, with illustrations by Sergeii Chekhonin, was published in (then) Leningrad 1925.

I was raised on translated Russian children’s stories (the only books of that genre we could access in the closed-economy, socialist misadventures of Sri Lanka during the early 1970s). Whatever economic realities that thrust those books on my childhood, many of them were very fine stories, always well illustrated. But I had somehow missed out on this one — so I quickly did some web searching for this story. And what a fantastic fable it is!

Tarankanische tells the nonsense tale of a threatening cockroach who is so fierce that he terrifies all the animals who are out to enjoy a picnic. Even the mighty elephants are helpless in his presence. The cockroach bullies and scares animals much larger than itself, and demands they surrender their cubs so he can eat them. He is seen as “a terrible giant: the red-haired, big-whiskered cockroach.”

In his essay titled Watching the Mighty Cockroach Fall, Philip Shishkin writes: “It is hard not to read the poem as an allegory for the rise and fall of a dictatorship. Despots tend to appear invincible while they rule, and then laughably weak when they fall. Once their subjects call them out on their farce, dictators look ridiculous. Often, they react by killing and jailing people, which buys them more time in power (Iran, Belarus, and Uzbekistan come to mind). But just as often, when faced with a truly popular challenge, dictators shrink to the size of their inner cockroaches.”

Shishkin then raises an interesting question: Did Kornei Chukovsky have Joseph Stalin in mind when he wrote it? Was Stalin prominent enough when the story was first published in 1925? To find out, read the full essay.

According to his mini-bio on IMDB, Chukovsky was a praised Russian translator of Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and other English and American authors. His writings for children are regarded as classics of the form. His best-known poems for children are “Krokodil”, “Moydodyr”, “Tarakanische”, and “Doctor Aybolit” (Doctor Ouch).