I’m just coming up for fresh air after two hectic weeks – this blog was silent during that time as I was deep immersed in doing something new and interesting.

With my team at TVE Asia Pacific, I’m involved in producing a new TV series started airing on May 22 on Sri Lanka’s ratings-leading, privately-owned, most popular channel, Sirasa TV.

Named Sri Lanka 2048, it is an innovative series of one-hour television debates that explore prospects for a sustainable future for Sri Lanka in the Twenty First Century.

Each debate will involves -– as panel and studio audience -– over two dozen Sri Lankans from academic, civil society, corporate and government backgrounds. They are recorded ‘as live’ and broadcast every Thursday at 10.45 pm, which, in Sri Lankan TV viewing patterns, is the favoured time for serious current affairs and political programmes.

The debates are being co-produced by TVE Asia Pacific, the educational media foundation that I head, in partnership with IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and MTV Channel (Private) Limited, which runs a bevy of radio and TV channels including Sirasa TV and Channel One MTV.

The editorially independent series will accommodate a broad spectrum of expertise and opinion.

The debates are based on topics such as managing our waste, reducing air pollution, protecting biodiversity on land and in the seas, and buffering communities from disasters. Two debates in English will look at the nexus between business and the environment, and coping with climate change.

Read detailed news story on TVEAP website

Read series line up and broadcast schedule

The series is based on the overall premise that Sri Lanka has abundant land and ocean resources that can be used to build such a future -– but it faces many challenges in taking the right action at the right time. We believe that public discussion and debate on issues, choices and alternatives is an essential part of this process. Read more on why this series.

Why 2048? For one thing, it’s the year Sri Lanka will mark 100 years of political independence. Being 40 years in the future, the year lies slightly more than a generation ahead, allowing ample time and opportunity to resolve deep-rooted problems of balancing development with conservation.

Sri Lanka 2048 follows an informal, talk show format that allows ample interaction between the panel and empowered audience. Although they take place within a clearly defined scope that enables some focus, all debates are unscripted.

Our amiable moderator Kingsly Rathnayaka (centre in the photo montage above), one of the most versatile presenters on Sri Lankan television today, keeps the panel and audience engaged. By design, we ask more questions than we are able to answer in a television hour (48 mins). But then, we don’t expect to resolve these burning issues in that time – all we can hope to do is to stretch the limits of public discussion.

Logistics and studio size limit the number of our audience to a two dozen. We’ve tried hard to ensure a good mix among them, drawn from all walks of life. To bring in additional voices and perspectives, we insert into each debate 2 or 3 short video reports produced in advance. These highlight solutions to environment or development problems that have been tried out by individuals, communities, NGOs, government agencies or private companies. Played at key points during debates, these help steer discussion in a particular direction.

We are already receiving favourable media reviews and coverage. Here are some that appeared in English language newspapers (more have come up in Sinhala newspapers, the language in which most of this series is produced and broadcast):

The Morning Leader, 28 May 2008: Timely action to sustain Sri Lanka’s development

The Sunday Times, 18 May 2008: TV Debate series to create a sustainable future

The Nation, 1 June 2008: Pick the best at Sri Lanka 2048

Sri Lanka 2048 is the culmination of months of research, development and pre-production work carried out by TVE Asia Pacific’s production team in collaboration with IUCN Sri Lanka. Our preparatory work involved consultations with dozens of experts, activists, officials, entrepreneurs – and their various organisations or companies. We synthesize and package their information, opinions and experiences with the dynamic and creative production team at MTV Channel (Pvt) Limited.

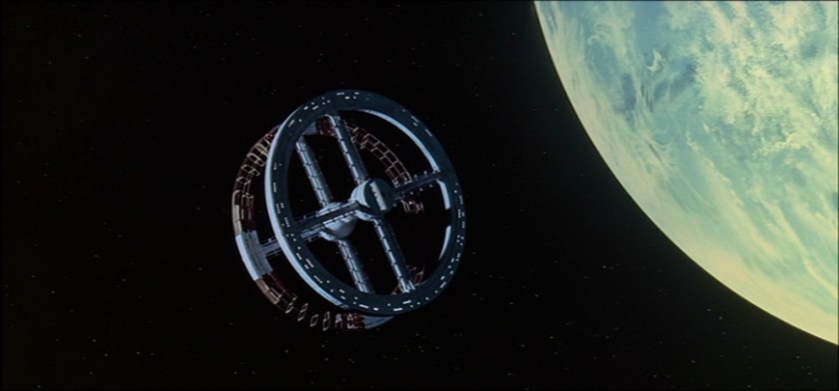

The inspiration for this series came from my mentor Sir Arthur C Clarke, with whom I wrote an essay 10 years ago that outlined his personal vision for his adopted country in 2048. The celebrated futurist that he was, Sir Arthur often said that there is a range of possible futures, and our actions – and inaction – determine what kind of future actually happens. Desirable futures don’t just happen; they need to be worked on.

Sri Lanka 2048 is an attempt to discuss how Sri Lankans can pursue economic prosperity without trading off their good health, natural wealth and public order. This is not a series preaching narrowly focused green messages to a middle class audience. We want to rise above and beyond the shrill of green activists, and engage in informed, wide ranging discussions on the tight-rope balancing act that emerging economies like Sri Lanka have to perform between short term economic growth and long term health of people and ecosystems.

Contrary to popular perception, ‘sustainable development’ is not some utopian or technical ideal of environmental activists. It’s about creating a liveable society here and today – where everyone has an acceptable quality of life, ample opportunities to learn and earn, and the freedom to pursue their own dreams.

Doing good television takes a good deal of time, effort and money. This TV series is supported under the Raising Environmental Consciousness in Society (RECS) project of IUCN Sri Lanka, which is funded by the Government of the Netherlands. But neither is responsible for editorial content or analysis, which rests on my shoulders as the executive producer of the series.

And I, in turn, stand on the shoulders of dedicated, hard working production teams drawn from TVE Asia Pacific and MTV Channel (Pvt) Limited. Doing good television is all team work.

All photos courtesy TVE Asia Pacific