“I haven’t had to do a nine-to-five job ever in my life, and that is a very envious situation to be in if you like the wild. Life has been much like a river in that it picks you up and carries you along. I have got into things as they come towards me.”

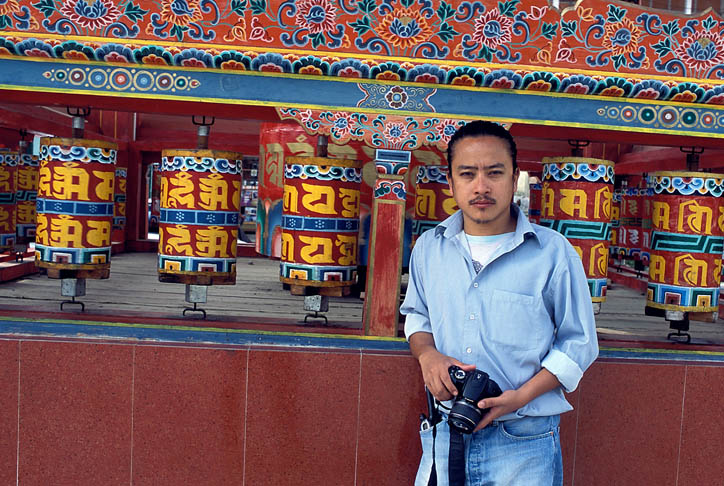

That’s how Romulus Whitaker, reptile and amphibian specialist, conservationist and filmmaker sums up his long, eventful and illustrious career. At 65, he is full of zest for life, ready to take on new challenges in protecting India’s forests and wildlife.

His current ambition, for which he has just been selected as an Associate Laureate in the 2008 Rolex Awards for Enterprise, is to create a network of rainforest research stations throughout India.

I caught up with this American-born, naturalised Indian citizen a few days ago when he and fellow Indian Moji Riba were presented with their Rolex awards at a ceremony in New Delhi.

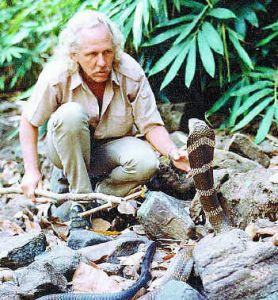

Of course, I’d heard about Romulus (Rom) Whitaker for years and seen some of his natural history films. In some ways, his style was a bit like that of ‘The Crocodile Hunter’ Steve Irwin — putting himself in the picture, sometimes in daring encounters with potentially dangerous animals…all in the name of bringing nature a bit closer to us in our living rooms.

But such similarities go only so far. Rom takes a less dramatic and more philosophical approach to humans’ relationship with Nature. For him, television is only a means to an end. As Rolex award profile put it, “the combination of a foreign name, mildly Viking looks inherited from his Swedish mother, an unexpected fluency in local Indian dialects and a thoroughly irreverent attitude” makes him “a highly unconventional yet effective conservationist in a country far from his birthplace”.

To catch a glimpse of this remarkable man, watch this ‘Incredible India’ PSA featuring Romulus Whitaker:

Rom was the founder director of the Snake Park in Chennai. The park was established in 1972 ‘to preserve the endangered reptile species in the sub continent’.

Rom’s career in film making was a byproduct of his life-long desire to bring people and Nature closer. He chronicled his venture into the world of television and film in a chapter he wrote for a book published by India’s Centre for Environment Education and TVE Asia Pacific in 2002. In that book, titled Wild Dreams, Green Screens, eight leading Indian film-makers shared insights about their careers, including how and when they decided to get involved in this field. They also talked about some of the exciting — and frustrating — experiences they have had while filming nature and wildlife.

In the early 1970s, Rom worked with a Russian film crew who turned up to do a sequence on snakes for a film based on the famous Kipling story, Rikki Tikki Tavi. “It was fun for me to help them figure out how to film a snake stealing an egg from a bird’s nest – and it took a whole week to do it. I was impressed by their patience and persistence,” Rom recalled in the book.

After that, every few months, some film crew would show up to do either a short news story on the Snake Park, or a short film on Indian snakes for foreign audiences. India’s stereotyped reputation as a land of snakes and snake-charmers partly fueled this interest.

Rom continues: “By the 1980s, I started thinking I knew something about making wildlife films – even though I didn’t have a TV, and there weren’t really very many such documentaries screened anywhere in India. I was aware that films could show and teach people about my beloved reptiles like nothing else. Surely the Snake Park with nearly a million visitors a year could make good use of such films, and I knew the visitors would go away with a new awareness of how beautiful, graceful and interesting reptiles are. A single broadcast on a TV channel and 20 million people would be able to see it all at once!”

Determined to do his own films, Rom teamed up with two school friends John and Louise Riber, and Shekar Dattatri, to make a film on India’s snakebite problem. They had a tiny budget (Indian Rupees 50,000, which is approximately US$ 1,000 today), an old Arri camera and ‘a lot of enthusiasm’.

One thing led to another. “‘Snakebite’ turned out to be a good little half-hour film which was translated into several Indian languages… Amazingly, this little film won a first prize at a festival in the United States, and was awarded the Golden Eagle by the American Movie and Television Federation. Lo and behold, I was a filmmaker!”

‘Snakebite’ (1985), made on 16 mm film, also launched the career of Shekar Dattatri, a multi-award winning Indian filmmaker who worked as an assistant director on this production. Coincidentally, Shekar was an Associate Laureate of the Rolex Award in 2004 for his ‘Wild India Project – Changing Hearts and Minds through Moving Images’.

We missed Shekar at the Delhi event – he couldn’t make it due to scheduling difficulties. But as Rom has written, the Whitaker-Dattatri partnership continued for several years while they struggled with ‘very crude equipment’ and tiny budgets. Films like ‘Seeds of Hope’ (on tree planting) and ‘A Cooperative for Snake Catchers’ followed.

Rom further writes in his chapter: “We worked hard on these films, learning as we went along month after month, working with really good people like the tree planters of Auroville and the Palni Hills Conservation Council, and, of course, the fantastic Irula tribals. We did have a few narrow escapes with snakes, but we always felt we were in much more danger driving down National Highway 45, than from any of our venomous subjects!”

Rom’s film making in the past two decades has taken him not only to the far corners of India, but to other biodiversity hotspots of the world – such as Indonesia. As the years passed, his enhanced reputation attracted big names in wildlife films, such as National Geographic, Discovery/Animal Planet and BBC Natural History. Combining his conservation knowledge with public education skills, Rom has also been presenter of several films.

These multiple involvements have earned him a string of awards – his documentary King Cobra made for National Geographic won him an Emmy award, considered the television equivalent of the Oscars.

Despite the rigorous demands of film making (and the occasional lure of television medium), Rom has remained active in conservation circles both within India and at global level. While many conservationists in India focus their attention on charismatic megafauna like tigers and elephants, Rom has stayed faithful to his chosen field of reptiles and amphibians. Years ago he realized that his beloved species cannot survive unless their natural habitats do. So, like many others, he evolved from naturalist to conservationist.

“A lot of us get wrapped up in our own little special animal and then we wake up and start thinking it has got to be habitat and it has to be eco-development that involves people and, now, in my case, it has crystallized into the whole idea of water resources,” he says.

Read his detailed CV for details on his conservation, publishing and film making accomplishments.

Rom’s colourful career has itself become a subject for other filmmakers. In 2007, he was featured in a critically-acclaimed documentary produced by PBS, under their “Nature” banner, on “super-sized” crocodiles and alligators, which was filmed in India, East Africa and Australia.

And in January 2009, Whitaker returned to the small screen in another “Nature” documentary on real-life reptiles such as Komodo dragons and Dracos that inspired tales of dragons.

Extract from The Dragon Chronicles, which premiered on PBS in January 2009:

Read the PBS/Dragon Chronicles interview with Rom Whitaker

The man who turned to moving images in the 1980s to move people’s minds towards conservation is still engaged in that business. He is a conservationist who puts a premium on public engagement, and especially on working with children and young people.

He says: “We are doing a lot of work with young people, bringing them to the forest and showing them what happens here and why it matters. It can be very difficult to change adult attitudes, but with the young, it is easier to get across the knowledge that what we are doing to the forests we are doing to ourselves.”