In my Ravaya column (in Sinhala) for 31 July 2011, I look back at South Africa’s HIV/AIDS misadventure under President Thabo Mbeki, who refused to accept the well-established scientific consensus about the viral cause of AIDS and the essential role of antiretroviral drugs in treating it. Instead, he and his health minister embarked on a highly dubious treatment using garlic, lemon juice and beetroot as AIDS remedies — all in the name of ‘traditional knowledge’.

It turned out to be a deadly experiment, and one of the worst policy debacles in the history of public health anywhere in the world. In 2008, A study by Harvard researchers estimated that the South African government could have prevented the premature deaths of 365,000 people if it had provided antiretroviral drugs to AIDS patients and widely administered drugs to help prevent pregnant women from infecting their babies.

There are lessons for all governments addressing complex, technical issues: do not allow a vocal minority to hijack the policy agenda, ignoring well established science and disallowing public debate on vital issues.

AIDS රෝගය මුලින් ම වාර්තා වී වසර තිහක් ගත වී තිබෙනවා. අමෙරිකාවේ මුල් වරට මේ රෝග ලක්ෂණ සහිතව රෝගීන් වාර්තා වන්නට පටන් ගත්තේ 1981දී. එයට හේතුව HIV නම් වයිරසය බව සොයා ගත්තේ ඊට දෙවසරකට පසුව.

අද HIV/AIDS ලෝක ව්යාප්ත වසංගතයක් හා ලෝකයේ ප්රධාන පෙළේ සංවර්ධන අභියෝගයක් බවට පත්ව තිබෙනවා. අළුත් ම සංඛ්යා ලේඛනවලට අනුව 2009 වන විට HIV ශරීරගත වී ජීවත්වන සංඛ්යාව මිලියන් 33ක්. අළුතෙන් ආසාදනය වන සංඛ්යාව වසරකට මිලියන් 2.6ක්. HIV ආසාදන උත්සන්න අවස්ථාවේ AIDS රෝගය ඇති වී මිය යන සංඛ්යාව වසරකට මිලියන් 2ට වැඩියි.

HIV/AIDS ගැන විවිධ කෝණවලින් විග්රහ කළ හැකියි. දුගී දුප්පත්කම, බලශක්ති අර්බුද, පරිසර දූෂණය හා ගැටුම්කාරී තත්ත්වයන්ට මුහුණ දෙන දියුණුවන ලෝකයේ බොහෝ රටවලට ගෙවී ගිය දශක තුන තුළ HIV/AIDS නම් අමතර අභියෝගයට ද මුහුණ දීමට සිදු වුණා. එයින් දැඩි සේ පීඩාවට පත් දකුණු අප්රිකාවේ HIV/AIDS ප්රතිපත්තිය වසර ගණනක් අයාලේ ගිය කථාවයි අද විග්රහ කරන්නේ. මෑතදී මා නැවතත් දකුණු අප්රිකාවට ගිය අවස්ථාවේ මගේ දැනුම අළුත් කර ගන්නට ලැබුණු නිසායි.

ලෝකයේ වැඩි ම HIV ආසාදිත ජන සංඛ්යාවක් සිටින රට දකුණු අප්රිකාවයි. 2007 දී HIV සමග ජීවත් වන දකුණු අප්රිකානුවන් සංඛ්යාව මිලියන් 5.7 ක් පමණ වුණා. එනම් මුළු ජනගහනය මිලියන් 48න් සියයට 12ක්. එය එරට සෞඛ්ය අර්බුදයක් පමණක් නොව සමාජයීය හා ආර්ථීක ප්රශ්නයක් ද වෙනවා.

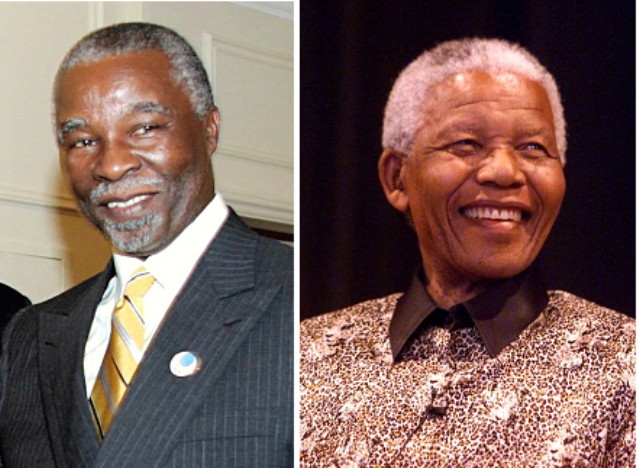

ජනාධිපති නෙල්සන් මැන්ඩෙලාගේ 1994-99 ධූර කාලයේ HIV/AIDS පිළිබඳව දකුණු අප්රිකාවේ සෞඛ්ය ප්රතිපත්ති සකස් වූයේ ලොව පිළිගත් වෛද්ය දැනුම හා උපදෙස් මතයි. HIV සමග ජීවත් වන අයට හැකි තාක් කල් නීරෝගීව දිවි ගෙවන්නට ඖෂධ සපයන අතරේ වයිරසය පැතිරයාම වැළැක්වීමේ දැනුවත් කිරීම් හා මහජන අධ්යාපන ව්යාපාරයක් දියත් වුණා.

එහෙත් ඔහුගෙන් පසු ජනාධිපති වූ තාබෝ එම්බෙකි (Thabo Mbeki) මේ ගැන ප්රධාන ප්රවාහයේ වෛද්ය විද්යාත්මක දැනුම ප්රශ්න කරන්නට පටන් ගත්තා. වෛද්ය විශේෂඥ දැනුමක් නොතිබුණත් තියුණු බුද්ධියකින් හෙබි එම්බෙකි, මෙසේ අසම්මත ලෙස සිතන්නට යොමු වුණේ HIV/AIDS ගැන විකල්ප මතයක් දරන ටික දෙනකුගේ බලපෑමට නතු වීම නිසයි.

මේ අයට ඉංග්රීසියෙන් AIDS Denialists කියනවා. ඔවුන්ගේ තර්කය AIDS රෝගය හට ගන්නේ HIV වයිරසය නිසා නොව දුප්පත්කම, මන්ද පෝෂණය වැනි සමාජ ආර්ථීක සාධක ගණනාවක ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙසින් බවයි.

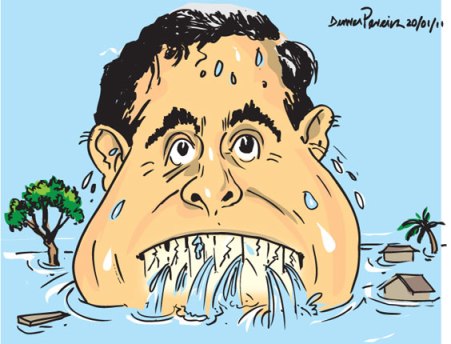

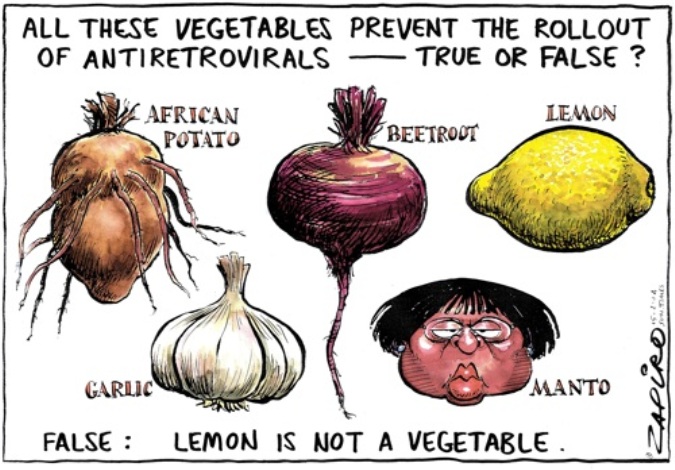

එම්බෙකිගේ සෞඛ්ය ඇමතිනිය (1999-2008) ලෙස ක්රියා කළ මාන්ටෝ ෂබලාලා සිමැංග් (Manto Tshabalala Msimang) මේ අවුල තවත් ව්යාකූල කළා. HIV ආසාදනය පාලනය කරන බටහිර වෛද්ය විද්යාවේ ඖෂධ වෙනුවට සම්ප්රදායික අප්රිකානු දැනුමට අනුව සුදුළුෑනු, දෙහි සහ බීට්රූට් යුෂ ගැනීම සෑහෙන බවට ඇය ප්රසිද්ධියේ ප්රකාශ කළා!

මේ නිසා HIV වයිරසයට ප්රහාර එල්ල කිරීම වෙනුවට දුප්පත්කම පිටුදැකීම කළ යුතු යයි ස්ථාවරයකට එම්බෙකි යොමු වුණා. HIV මර්දන සෞඛ්ය කටයුතු අඩපණ කරන්නටත්, මහජන සෞඛ්ය සේවා හරහා ඖෂධ ලබා දීම නතර කිරීමටත් එම්බෙකි රජය පියවර ගත්තා.

HIV සමග ජීවත්වන බහුතරයක් දකුණු අප්රිකානුවන්ට AIDS රෝග ලක්ෂණ පහළ වී නැහැ. HIV ශරීරගත වීමෙන් පසු වසර හෝ දශක ගණනක් ජීවත්වීමේ හැකියාව අද වන විට වෛද්ය විද්යාත්මකව ලබා ගෙන තිබෙනවා. එහෙත් ඒ සඳහා නිතිපතා Anti-Retroviral (ARV) ඖෂධ ගැනීම අවශ්යයි.

බොහෝ දියුණු වන රටවල අඩු ආදායම් ලබන HIV ආසාදිතයන්ට මේ ඖෂධ ලබා දෙන්නේ රජයේ වියදමින්. HIV ආසාදිත කාන්තාවන්ට ARV ඖෂධ නිසි කලට ලැබුණොත් ඔවුන් බිහි කරන දරුවන්ට මවගෙන් HIV පැතිරීම වළක්වා ගත හැකියි. එහෙත් එම්බෙකි රජය HIV වයිරසය ගැන විශ්වාස නොකළ නිසා ප්රජනන වියේ සිටින HIV ආසාදිත කාන්තාවන්ට එම ඖෂධ දීමත් නතර කළා.

දකුණු අප්රිකාව ජාතීන්, භාෂා හා දේශපාලන පක්ෂ රැසක සම්මිශ්රණයක්. එමෙන් ම 1994 සිට නීතියේ ආධිපත්යය හා රාජ්යයේ බල තුලනය පවතින රටක්. ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී සම්ප්රදායයන් හා ආයතන ප්රබල කරන්නට සැබෑ උත්සාහ ගන්නා රටක්.

මෙබඳු රටක වුවත් වසර කිහිපයක් පුරා ජනාධිපතිවරයාට හා සෞඛ්ය ඇමතිනියට මෙබඳු ප්රබල ප්රශ්නයකදී මේ තරම් අයාලේ යන්නට ඉඩ ලැබුණේ කෙලෙසදැයි මා එරට විද්යාඥයන් හා මාධ්යවේදීන් කිහිප දෙනකුගෙන් ඇසුවා. ඔවුන් දුන් පිළිතුරුවල සම්පිණ්ඩනය මෙයයි.

තාබෝ එම්බෙකි යනු වර්ණභේදවාදයට එරෙහිව දශක ගණනක් අරගලයක යෙදුණු, පාලක ANC පක්ෂයේ ප්රබල චරිතයක්. ඔහුගේ දේශපාලන කැපවීම පිළිබඳව විවාදයක් නැහැ. මැන්ඩෙලා 1994දී ජනාධිපති වන විට එම්බෙකි උප ජනාධිපති වුණා.

1994-99 කාලය තුළ එරට ආර්ථීක වර්ධනයට හා සමාජ සංවර්ධනයට නායකත්වය සැපයූ ඔහු අප්රිකානු කලාපයේ දක්ෂ රාජ්ය තාන්ත්රිකයකු ලෙස නමක් දිනා ගත්තා. මැන්ඩෙලා එක් ධූර කාලයකින් පසු කැමැත්තෙන් විශ්රාම ගිය විට එම්බෙකි ANC ජනාධිපති අපේක්ෂකයා වී ජයග්රහණය කළා.

පරිණත දේශපාලකයකු රටේ ජනාධිපති ලෙස මහජන ඡන්දයෙන් තේරී පත්ව සිටින විටෙක, වැරදි උපදෙස් නිසා එක් වැදගත් ප්රශ්නයක් සම්බන්ධයෙන් ඔහු නොමග යාමට අභයෝග කරන්නේ කෙසේ ද? දකුණු අප්රිකාවේ වෛද්යවරුන් හා අනෙක් විද්වතුනට තිබූ ප්රශ්නය එයයි. සාම්ප්රදායික දැනුම එක එල්ලේ හෙළා නොදැක, එහි සීමාවන් ඇති බව පෙන්වා දෙමින්, රටේ නායකයා හා සෞඛ්ය ඇමති සමග හරවත් සංවාදයක යෙදෙන්නට සීරුවෙන් හා සංයමයෙන් කටයුතු කරන්නට ඔවුන්ට සිදු වුණා.

ANC පක්ෂය තුළ ම එම්බෙකිගේ HIV/AIDS ස්ථාවරය ගැන ප්රශ්න මතු වුණා. එහෙත් මැන්ඩෙලා මෙන් විකල්ප අදහස් අගය කිරීමේ හැකියාවක් එම්බෙකිට නොතිබූ නිසාත්, ජනාධිපති හැටියට වඩා ඒකමතික පාලනයක් ඔහු ගෙන යන්නට උත්සාහ කළ නිසාත් පක්ෂය ඇතුළෙන් දැඩි ප්රතිරෝධයක් ආවේ නැහැ.

2002 දී පැවති ANC පක්ෂ රැස්වීමකදී මැන්ඩෙලා මේ ගැන සාවධානව අදහස් දැක් වූ විට එම්බෙකි හිතවාදියෝ ‘ජාතියේ පියා’ හැටියට අවිවාදයෙන් සැළකෙන මැන්ඩෙලාට වාචිකව ප්රහාර එල්ල කළා. එයින් පසු මැන්ඩෙලා ද තම අනුප්රාප්තිකයාගේ HIV/AIDS ප්රතිපත්ති ප්රසිද්ධියේ ප්රශ්න කිරීමෙන් වැළකුණා.

එම්බෙකි හිතවාදියෝ එතැනින් නතර වුණේ නැහැ. සිය නායකයාගේ අසම්මත HIV/AIDS න්යායට එරෙහිව කථා කරන විද්යාඥයන් හා වෛද්යවරුන්ට මඩ ප්රහාර දියත් කළා. දකුණු අප්රිකාවේ සිටින ලොව පිළිගත් ප්රතිශක්තිවේදය පිළිබඳ විශේෂඥයකු වූ මහාචාර්ය මක්ගොබා (Prof Malegapura Makgoba) ජනාධිපතිගෙන් ඉල්ලා සිටියා ලොව හිනස්සන මේ න්යායෙන් අත් මිදෙන ලෙස.

මේ මහාචාර්යවරයා බටහිර විද්යාවට ගැතිකම් කරන, අප්රිකාවේ සාම්ප්රදායික දැනුම හෙළා දකින්නකු ලෙස ජනාධිපති කාර්යාලය විසින් හදුන්වනු ලැබුවා. සුදු ජාතික හෝ ඉන්දියානු සම්භවය සහිත විද්වතකු ජනාධිපති මතවාද ගැන ප්රශ්න කළ විට එය ‘කළු ජාතික නායකයාට අවමන් කිරීමේ’ සරල තර්කයකට ලඝු කරනු ලැබුවා.

මේ මඩ ප්රහාර හා රාජ්ය යාන්ත්රණයට එරෙහිව හඬක් නැගූ සුදු හා කළු ජාතික දකුණු අප්රිකානුවන් ටික දෙනකු ද සිටියා. ඔවුන් විද්යා ක්ෂෙත්රයෙන් පමණක් නොව සාහිත්ය, කලා සහ සාමයික ක්ෂෙත්රවලින් ද මතුව ආවා.

එහිදී දැවැන්ත කාර්ය භාරයක් ඉටු කළේ කේප්ටවුන්හි ආච්බිෂොප් ඩෙස්මන්ඩ් ටූටූ. වර්ණභේදවාදයට, අසාධාරණයට හා දිළිඳුබවට එරෙහිව දශක ගණනක් තිස්සේ අරගල කරන, 1984 නොබෙල් සාම ත්යාග දිනූ ඔහු, මුළු ලෝකය ම පිළිගත් චරිතයක්. 1994න් පසු ඡන්දයෙන් බලයට පත් හැම රජයක ම හොඳ දේ අගය කරන අතර වැරදි ප්රතිපත්ති නොබියව විවේචනය කරන්නෙක්.

ඩෙස්මන්ඩ් ටූටූ මුලදී පෞද්ගලිකවත් පසුව මහජන සභාවලත් එම්බෙකිගේ HIV/AIDS මංමුලාව ගැන කථා කළා. මහජන උන්නතියට ඍජුව ම බලපාන මෙබඳු ප්රශ්න සම්බන්ධයෙන් විවෘත සංවාදයක් පැවතිය යුතු බවත්, බහුතර විද්වත් මතයට ගරු කිරීම ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී රජයක වගකීම බවත් ඔහු අවධාරණය කළා.

2004 දී එක් ප්රසිද්ධ දේශනයකදී ඔහු කීවේ: “සුදු පාලකයන්ට එරෙහිව අරගල කරන සමයේ අපි ඉතා ප්රවේශමෙන් කරුණු ගවේෂණය කර, තර්කානුකූලව ඒවා ඉදිරිපත් කළා. දැන් ටිකෙන් ටික ඒ වෙනුවට එහෙයියන්ගේ හා ප්රෝඩාකාරයන්ගේ සම්ප්රදායක් ඉස්මතු වෙමින් තිබෙනවා. HIV/AIDS ගැන ජනාධිපති එම්බෙකිගේ විශ්වාස මීට වඩා බෙහෙවින් විවාදයට ලක් කළ යුතුයි. අභියෝග හා විවාදවලට ලක් කිරීමෙන් සත්යයට හානි වන්නේ නැහැ. එය වඩාත් නිරවුල් වෙනවා. මෙසේ ප්රශ්න කිරීම නිසා මා ජනාධිපතිගේ හතුරකු වන්නේ නැහැ. ජනසම්මතවාදී සමාජවල නායකයා කියූ පළියට යමක් පරම සත්යය වන්නේ නැහැ. එය තර්කානුකූල හා සාක්ෂි මත පදනම් වී ඇත්දැයි විවාදාත්මකව විග්රහ කිරීම අත්යවශ්යයි.”

1991 නොබෙල් සාහිත්ය ත්යාගය දිනූ සුදු ජාතික දකුණු අප්රිකානු ලේඛිකා නැඩීන් ගෝඩිමර් ද මේ සංවාදයට එක් වුණා. 2004 දී ඇය ප්රසිද්ධ ප්රකාශයක් කරමින් කීවේ ජනාධිපති එම්බෙකීගේ අනෙක් සියළු ප්රතිපත්ති තමා අනුමත කරන නමුත් HIV/AIDS ගැන ඔහුගේ ස්ථාවරය පිළි නොගන්නා බවයි.

දකුණු අප්රිකාවේ ස්වාධීන ජනමාධ්ය ද ජනාධිපති හා ඇමතිනියන්ගේ HIV/AIDS මනෝ විකාර දිගට ම විවේචනය කළා. ඇමතිනියට Madam Beetroot හෙවත් ‘බීට්රූට් මැතිනිය’ යන විකට නාමය දෙනු ලැබුවා. එහෙත් මේ දෙපළ දිගු කලක් තම වැරදි මාර්ගයෙන් ඉවත් වූයේ නැහැ. විවේචකයන්ගේ දේශපාලන දැක්ම, ජාතිය හා සමේ වර්ණය අනුව යමින් මේවා හුදෙක් ‘විරුද්ධවාදීන්ගේ කඩාකප්පල්කාරී වැඩ’ ලෙස හඳුන්වා දුන්නා.

2002 වන විට ANC පක්ෂය තුළින්, රට තුළින් හා ජාත්යන්තර විද්වත් සමූහයා වෙතින් මතුව ආ ප්රබල ඉල්ලීම් හමුවේ ජනාධිපති එම්බෙකි එක් පියවරක් ආපස්සට ගත්තා. එනම් ආන්දෝලනයට තුඩු දුන් HIV/AIDS ප්රතිපත්ති ගැන මින් ඉදිරියට ප්රසිද්ධියේ කිසිවක් නොකීමට. ජනාධිපති මෙසේ මුනිවත රැක්කත් සෞඛ්ය ඇමතිනියගේ අයාලේ යාම තවත් කාලයක් සිදු වුණා.

2003 දී විශ්රාමික අමෙරිකානු ජනාධිපති බිල් ක්ලින්ටන් එම්බෙකි හමු වී පෞද්ගලික ආයාචනයක් කළා. නොමග ගිය දකුණු අප්රිකානු HIV/AIDS ප්රතිපත්ති නැවත හරි මඟට ගන්නට ක්ලින්ටන් පදනම විද්වත් හා මූල්ය ආධාර දීමට ඉදිරිපත් වූ විට එම්බෙකි එය පිළි ගත්තා. (මෙය ප්රසිද්ධ වූයේ වසර ගණනාවකට පසුවයි.)

එහෙත් එරට HIV/AIDS ප්රතිපත්ති යළිත් ප්රධාන ප්රවාහයට පැමිණීම එම්බෙකිගේ ධූර කාලය හමාර වන තුරු ම හරිහැටි සිදුවුණේ නැහැ. 2008 සැප්තැම්බරයේ ඔහු තනතුරින් ඉල්ලා අස් වූ පසු කෙටි කලකට ජනාධිපති වූ කලේමා මොට්ලාතේ තනතුරේ මුල් දිනයේ ම එම්බෙකිගේ සෞඛ්ය ඇමතිනිය ඉවත් කළා. ඒ වෙනුවට HIV/AIDS සම්බන්ධයෙන් කාගේත් විශ්වාසය දිනාගත් බාබරා හෝගන් සෞඛ්ය ඇමති ලෙස පත් කළා. ඇය ප්රතිපත්ති හරි මගට ගන්නට හා ARV ප්රතිකාර ව්යාප්ති කරන්නට ඉක්මන් පියවර ගත්තා.

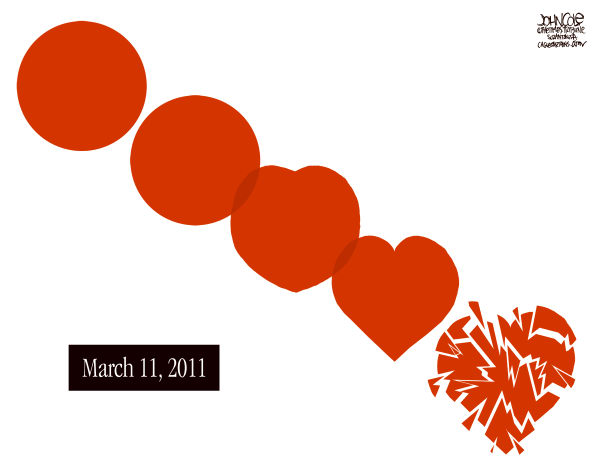

එහෙත් ඒ වන විට අතිවිශාල හානියක් සිදු වී හමාරයි. 2008 නොවැම්බරයේ අමෙරිකාවේ හාවඩ් සරසවියේ පර්යේෂකයෝ ගණන් බැලීමක් කළා. 2002-2005 වකවානුවේ නොමග ගිය HIV/AIDS ප්රතිපත්ති නිසා ප්රතිකාර හා සෞඛ්ය පහසුකම් අහිමි වූ දකුණු අප්රිකානුවන් සංඛ්යාව පිළිබඳව. ඍජු හෝ වක්ර වශයෙන් 365,000ක් දෙනා මේ අවිද්යාත්මක ප්රතිපත්ති නිසා අකාලයේ මිය ගිය බව ඔවුන්ගේ නිගමනයයි. (ක්රමවේදය සඳහා බලන්න: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/magazine/spr09aids/)

මේ ජීවිත හානි වලට වගකිව යුත්තේ කවුද?

දිවි සුරකින දැනුම සම්බන්ධයෙන් සෙල්ලම් කරන්නට යාමේ අවදානම හා එහි භයානක ප්රතිඵලවලට දකුණු අප්රිකාවේ HIV/AIDS මංමුලාව මතක හිටින පාඩමක්.