In this Ravaya column (in Sinhala), I summarise the views of late Dr Ray Wijewardene on sustainable farming. Written to mark his first death anniversary, it is the beginning of a series of explorations of his critical thinking on issues of agriculture, energy, environmental conservation and innovation.

This first appeared in Ravaya Sunday broadsheet newspaper on 21 August 2011.

See also next week’s column:

28 Aug 2011: සිවුමංසල කොලූගැටයා #29: වෙලට නොබැස පොතෙන් ගොවිතැන් කරන කෘෂි විද්යාඥයෝ

‘ඔබ මෙහි ආවේ කොහොම ද?’

ආචාර්ය රේ විජේවර්ධන තමන් හමු වන්නට ආ අමුත්තන්ගෙන් නිතර මේ ප්රශ්නය ඇසුවා. බොහෝ දෙනකුගේ උත්තරය වූයේ මෝටර් රථයකින් හෝ බස් රථයකින් පැමිණි බවයි.

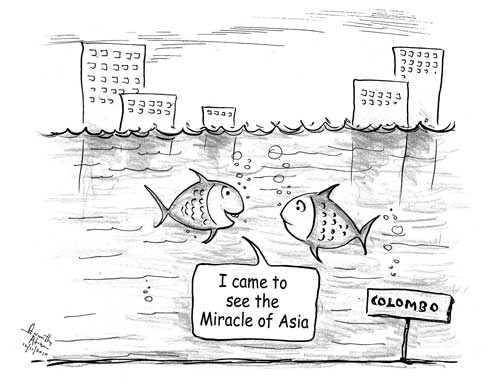

“ඔබ පැමිණ ඇත්තේ පිටරටින් ගෙනා වාහනයක්, පිටරටින් ගෙනා ඛනිජ තෙල් දහනය කරමින්, පිටරටින් ම ගෙනා තාර දමා තැනූ මහ පාරක් ඔස්සේයි.” එවිට ඔහු කියනවා. “ඉතින් ඔබ තවමත් සිතනව ද මේ නිදහස් හා ස්වාධීන රටක් කියා?’

මේ ප්රශ්නය දුසිම් ගණනක් දෙනා සමග රේ විජේවර්ධන මතු කරන්නට ඇති. ඒ තරමට ඔහු එබඳු දේ ගැන දිවා රාත්රී කල්පනා කළා. හැකි සෑම අවස්ථාවක ම රටේ විද්වතුන්, පාලකයන් හා ව්යාපාරිකයන්ගේ අවධානය යොමු කළා.

ඉංග්රීසියෙන් නිදහසට කියන ‘independent’ යන වචනයට වඩා ඔහු කැමති වූයේ ‘non-dependent’ යන්නටයි. අපේ මූලික අවශ්යතා හැකි තාක් දුරට අප ම සම්පාදනය කර ගැනීමෙන් පමණක් අපේ රටට සැබෑ නිදහසක් හා ස්වාධීපත්යයක් ලද හැකි බව ඔහු තරයේ විශ්වාස කළා.

විද්යා ජ්යොති, දේශමාන්ය ආචාර්ය පිලිප් රේවත (රේ) විජේවර්ධන අපෙන් වියෝ වී වසරක් පිරෙන මේ මොහොතේ ඔහුගේ අදීන චින්තනය ගැන ටිකක් කථා කරමු.

ඉංජිනේරුවකු හැටියට බි්රතාන්යයේ කේම්බි්රජ් සරසවියේ ඉගෙනුම ලැබූවත් ඔහු පසු කලෙක තමන් හදුන්වා දුන්නේ ‘ගොවියකු හා කාර්මිකයකු’ හැටියටයි (farmer and mechanic). පොතේ දැනුම හා න්යායයන්ට වඩා ප්රායෝගික අත්දැකීම් හා අත්හදා බැලීමෙන් ලබා ගන්නා අවබෝධය ඉතා වටිනා බව ඔහු නිතර ම කියා සිටියා.

බටහිර සම්ප්රදායට විද්යා අධ්යාපනයක් හා තාක්ෂණ පුහුණුවක් ලද ඔහු, පසු කලෙක තම උත්සාහයෙන් පෙරදිගට හා ශ්රී ලංකාවට උරුම වූ දේශීය දැනුම ප්රගුණ කළා. එහෙත් ඇතැම් අන්තවාදීන් මෙන් එක් දැනුම් සම්ප්රදායක එල්බ ගෙන අනෙක් සියළු දැනුම් සම්ප්රදායන් හෙළා දැකීමක් කළේ නැහැ. ඒ වෙනුවට ඔහු පෙර-අපර දෙදිග යා කරමින්, හැම තැනින් ම හරවත් හා ප්රයෝජනවත් දැනුම උකහා ගනිමින් අපේ කාලයේ සංවර්ධන අභියෝගයන්ට ප්රතිචාර දැක්විය හැකි ක්රමෝපායයන් සොයා ගියා.

කෘෂිකර්මය, බලශක්තිය, ඉඩම් පරිහරණය හා පරිසර සංරක්ෂණය යන ක්ෂෙත්ර හතරේ නිරවුල් හා නිවහල් දැක්මක් මත පදනම් වූ ප්රායෝගික ප්රතිපත්ති, කි්රයාමාර්ග හා විසඳුම් රාශියක් ඔහු යෝජනා කළා. රේ විජේවර්ධනට කළ හැකි ලොකු ම ගෞරවය නම් ඔහු එසේ දායාද කළ දැනුම් හා අදහස් සම්භාරය ප්රයෝජනයට ගැනීමයි.

කුඩා වියේදී රේට උවමනා වුණේ අහස්යානා පදවන්න හා නිපදවන්න. එහෙත් උපන් රටට වඩා ප්රයෝජනවත් වන ශාස්ත්රයක් උගන්නා හැටියට පියා දුන් අවවාදයට අනුව ඔහු කෘෂිකර්ම ඉංජිනේරු විද්යාව (agricultural engineering) හදාරා පසු කලෙක ශෂ්ය විද්යාව (agronomy) පිළිබඳ විශේෂඥයකු වුණා. නමුත් එම ක්ෂෙත්රයට ප්රවේශ වන වෙනත් විද්වතුන් මෙන් පොතෙන් ගොවිතැන් කිරීමට හෝ විද්යාගාරවල පර්යේෂණ කිරීමට හෝ පමණක් ඔහු සීමා වුණේ නැහැ.

හේන් ගොවියාට හා වෙල් ගොවියාට බලපාන ගැටළු හා අභියෝග හඳුනා ගන්නට ඔහු ඔවුන් සමග ගොවි බිම් හා වෙල්යායවල කල් ගත කළා. මුළු ජීවිත කාලය පුරා ම කෘෂිකර්මය පිළිබඳ ඔහුගේ දැක්මට පාදක වුණේ කුඩා ගොවියාගේ ජීවන තත්ත්වය නගා සිටුවීම හා ගොවිතැනේදී කුඩා පරිමාන ගොවීන් හා ගෙවිලියන්ගේ පරිශ්රමය වඩාත් කාර්යක්ෂම කිරීමයි.

හරිත විප්ලවය (Green Revolution) 1950 දශකයේ ආරම්භ වන අවධියේ තරුණ විද්යාඥයකු හා ඉංජිනේරුවකු හැටියට රේ විජේවර්ධනත් එහි කොටස්කරුවකු වුණා. ඝර්ම කලාපීය රටවල කුඩා ගොවීන්ට ලෙහෙසියෙන් හැසිරවිය හැකි, නඩත්තුව වඩාත් පහසු වූ රෝද දෙකේ අත් ට්රැක්ටරයක් ඔහු නිර්මාණය කළා. බි්රතාන්යයේ සමාගමක් මගින් LandMaster නමින් 1960 හා 1970 දශකවල ලොව පුරා අලෙවි කළේ මේ නිර්මාණයයි.

එහෙත් වසර කිහිපයකින් ඔහු තම නිර්මාණයේ සැබෑ සීමාවන් හඳුනා ගත්තා. 1964 දී අමෙරිකාවේ හාවඞ් සරසවියේ ව්යාපාරික පාසලේ තම නිර්මාණය පිළිබඳව තොරතුරු ඉදිරිපත් කරන විට සභාවේ සිටි සුප්රකට අමෙරිකානු නිපැයුම්කරු හා ඉංජිනේරු බක්මින්ස්ටර් ෆුලර් (Buckminster Fuller) රේට මෙහෙම ප්රශ්නයක් මතු කළා: “ඔබේ ට්රැක්ටරය කළේ ගොවිතැන් කටයුතු යාන්ත්රික කිරීම ද? නැත්නම් මීහරකා යාන්ත්රික කිරීම ද?”

20 වන සියවසේ තාක්ෂණ කේෂත්රයේ දැවැන්තයකු මතු කළ මේ සරල ප්රශ්නය හමුවේ තමන් නිරුත්තර වූ බවත්, ඒ ඔස්සේ දිගට කල්පනා හා සංවාද කිරීමෙන් පසු කෘෂිකර්මය පිළිබඳ එතෙක් තිබූ ආකල්ප මුළුමනින් ම වෙනස් කරගත් බවත් රේ පසුව ඉතා නිහතමානීව ප්රකාශ කළා. එම තීරණාත්මක මුණ ගැසීමෙන් අනතුරුව බක්මින්ස්ටර් ෆුලර් හා රේ විජේවර්ධන සමස්ත හරිත විප්ලවය විචාරශීලීව විග්රහ කළා. රේ එතැන් පටන් සිය ජීවිත කාලය ම කැප කළේ සොබා දහමට වඩාත් සමීප වන ගොවිතැන් කිරීමේ ක්රම ප්රගුණ කරන්නට හා ප්රචලිත කරන්නටයි. පරිසරයට හිතකර ගොවිතැන (conservation faming) අපට අළුත් දෙයක් නොවන බව ඔහු පෙන්වා දුන්නා.

පසු කලෙක (1995) ඔහු හරිත විප්ලවය දෙස හැරී බැලූවේ මේ විදියටයි. “හරිත විප්ලවයේ ප්රධාන අරමුණ වුණේ හැකි තාක් බාහිර එකතු කිරීම් (රසායනික පොහොර, කෘමි නාශක, වල් නාශක, දෙමුහුම් බීජ වර්ග) හරහා අස්වැන්න වැඩි කිරීමයි. එහෙත් එහිදී අප අමතක කළ දෙයක් තිබුණා. ගොවින්ට අවශ්ය හුදෙක් අස්වනු වැඩි කර ගැනීමට පමණක් නොවෙයි. ගොවිතැනින් හැකි තරම් වැඩි වාසියක් හා ලාබයක් උපයා ගන්නටයි. නමුත් හරිත විප්ලවය හඳුන්වා දුන් හැම දෙයක් ම මිළට ගන්නට යාමේදී ගොවියාගේ නිෂ්පාදන වියදම ඉහළ ගියා. එයට සාපේක්ෂව (අස්වනු වැඩි වූවත්) ඔවුන්ගේ ශුද්ධ ලාභය එතරම් වැඩි වූයේ නැහැ. ඔවුන්ගේ ණයගැති භාවය නම් වැඩි වුණා. ඊට අමතරව බාහිර රසායනයන් අධිකව එක් කිරීම නිසා ගොවිබිම්වල ස්වාභාවික පරිසරය දරුණු ලෙස දුෂණයට ලක් වුණා.”

අද මේ කරුණු බොහෝ දෙනා පිළි ගෙන ඇතත් 1960 දශකය අගදී රේ මෙබඳු අදහස් ප්රසිද්ධියේ ප්රකාශ කළ විට ඒවා මනෝ විකාර හා සංවර්ධන-විරෝධී, කඩාකප්පල්කාරී අදහස් හැටියට සැළකුණා. බතින් බුලතින් රට ස්වයංපෝෂණය කිරීමේ ඒකායන ඉලක්කයට කොටු වී සිටි දේශපාලකයන්ට හා නිලධාරීන්ට මේ අදහස්වල වටිනාකම වැටහුනේ බොහෝ කලක් ගත වූ පසුවයි.

ප්රශ්නයක් මතු කළ හැම විට ම එයට හොඳ විසඳුම් සොයා යාමේ මාහැගි පුරුද්දක් රේට තිබුණා. හරිත විප්ලවය බලාපොරොත්තු වූ තරම් දිගු කාලීන වාසි ලබා නොදුන් නිසා එයට විකල්ප සෙවීම අවශ්ය වුණා. එහිදී ඔහු නවීන විද්යා දැනුම ප්රතික්ෂෙප කළේ නැහැ. දෙවන ලෝක යුද්ධයේ නිමාවෙන් පසු ලොව පුරා සීඝ්රයෙන් වර්ධනය වූ ජනගහනයට සරිලන තරමට ආහාර නිෂ්පාදනය වැඩි කිරීමේ ප්රායෝගික අවශ්යතාවය ඔහු හොඳ හැටි දුටුවා.

ඔහු කියා සිටියේ පෙරදිග අපේ වැනි රටවල දිගු කලක් තිස්සේ ගොවිතැන් සඳහා යොදා ගත් දේශීය දැනුම කාලීන අවශ්යතාවයන්ට අනුව සකසා ගැනීමෙන් වඩාත් කාර්යක්ෂම, පරිසරයට මෙන් ම අපේ සෞඛ්යයටද හිතකර ආහාර බෝග නිෂ්පාදනයකට යොමු විය හැකි බවයි. මෙය හඳුන් වන්නේ low external input sustainable agriculture (LEISA) කියායි.

මා රේ විජේවර්ධන හඳුනා ගත්තේ 1980 දශකය මැද දී. ඔහු ඉතා නිහතමානී ලෙසින් හා උද්යොගයෙන් තරුණ විද්යා ලේඛකයකු හා පුවත්පත් කලාවේදීයකු වූ මගේ ප්රශ්නවලට පිළිතුරු දුන්නා. ඔහුගේ විෂය ක්ෂෙත්රයන්ට අදාල කරුණක් ගැන අසා දැන ගැනීමට ඕනෑ ම වේලාවක දුරකථනයෙන් හෝ මුණගැසී හෝ කථාකිරීමේ අවකාශය ඔහු ලබා දුන්නා.

ඒ බොහෝ අවස්ථාවල ඔහුගේ ඉල්ලීම වූයේ ඔහුගේ නම සඳහන් නොකර නව අදහස් හා තොරතුරු මගේ පාඨකයන්ට බෙදා දෙන ලෙසයි. විශ්වාසනීයත්වය වඩාත් තහවුරුවන්නේ ඒවා මූලාශ්ර සමග ම ප්රකාශයට පත් කිරීම බව මා පහදා දුන් විට ඔහු එය පිළි ගත්තා. නමුත් සමහර විද්වතුන් මෙන් ඔහු කිසි දිනෙක මාධ්ය ප්රසිද්ධිය සොයා ගියේ නැහැ. මේ රටේ බොහෝ දෙනකු රේ විජේවර්ධනගේ හපන්කම් හා චින්තනය ගැන නොදන්නේ ඒ නිසා විය හැකියි.

1995 මැද දී ඉන්දියාවේ මුල් පෙළේ විද්යා ලේඛකයකු හා පරිසර චින්තකයකු වූ අනිල් අගර්වාල් (Anil Agarwal) මගෙන් සුවිශේෂී ඉල්ලීමක් කළා. ඔහුගේ සංස්කාරකත්වයෙන් පළ කරන Down to Earth විද්යා හා පරිසර සඟරාව සඳහා රේ සමග සම්මුඛ සාකච්ජාවක් කරන ලෙසට.”රේ කියන්නේ දියුණුවන ලෝකයේ සිටින අංක එකේ කෘෂි හා ශෂ්ය විද්යා විශේෂඥයකු පමණක් නොවෙයි, අපට සිටින ඉතාම ස්වාධීන හා නිර්මාණශීලී චින්තකයෙක්” අනිල් මට කියා සිටියා.

අනිල්ගේ ඉල්ලීම පරිදි මා රේ සමග දීර්ඝ සම්මුඛ සාකච්ඡුාවක් පටිගත කළා. එයට වරු දෙක තුනක් ගත වූ බවත්, එහි තොරතුරු සම්පූර්ණ කරන්නට තව දින ගණනාවක් වෙහෙස වූ සැටිත් මට මතකයි. එහි සාරාංශයක් Down to Earth සඟරාවේ 1995 ඔක්තෝබර් 31 කලාපයේ පළ වුණා. වී ගොවිතැන, හේන් ගොවිතැන, හරිත විප්ලවය හා එහි අහිතකර ප්රතිඵල, බලශක්ති අර්බුදයට දේශීය පිළියම් ආදී තේමා රැසක් ගැන අප කථා කළා.

තමා මාධ්යවේදියකු සමග කළ වඩාත් ම විස්තරාත්මක හා ගැඹුරු සංවාදය එය බව රේ පසුව මට කීවා. එහි සම්පූර්ණ සාකච්ජා පිටපත වසර 15ක් මගේ ලේඛන ගොනුවල රැදී තිබුණා. අන්තිමේදී රේගේ අවමංගල්යය පැවැත් වුණු දිනයේ, එනම් 2010 අගෝස්තු 20දා, එය මා groundviews.org වෙබ් අඩවිය හරහා පළ කළා. සාකච්ජාව කියවීමට පිවිසෙන්න: http://tiny.cc/RayBye

රේ විජේවර්ධන චින්තනය පිළිබඳ නව වෙබ් අඩවියක් ද මේ සතියේ එළි දකිනවා.