This is my latest Sinhala column published in Ravaya newspaper on 23 October 2011, which is about human-elephant interactions in Sri Lanka, which has the highest density of Asian elephants in the world. I have covered much of the same ground in English in another recent essay, Chandani: Riding a Jumbo Where No Woman Has Gone Before…

ඔක්තෝබර් මුල සතියේ කොළඹින් ඇරඹුණු, ගාල්ල මහනුවර හා යාපනය නගරවලට ද යන්නට නියමිත යුරෝපීය චිත්රපට උළෙලේ ප්රදර්ශනය කළ එක් චිත්රපටයකට මගේ විශේෂ අවධානය යොමු වුණා. ජර්මන් චිත්රපට කණ්ඩායමක් ලංකාවේ රූපගත කොට 2010දී නිර්මාණය කළ එය, Chandani: The Daughter of the Elephant Whisperer නම් වාර්තා චිත්රපටයක්. සිංහලෙන් ‘චාන්දනී – ඇත්ගොව්වාගේ දියණිය’ සේ අරුත් දිය හැකියි. අපේ රටේ ඈත අතීතයට දිව යන අලි – මිනිස් සබදතාවන්ගේ අළුත් පැතිකඩක්, කථාවක ස්වරූපයෙන් කියන නිර්මාණයක් හැටියට මේ චිත්රපටය මා දකිනවා.

අලි ඇතුන් ගැන චිත්රපට නිපදවන්නට සිනමාවේ මෙන් ම ටෙලිවිෂන් කර්මාන්තයේත් බොහෝ දෙනා කැමතියි. ගොඩබිම වෙසෙන විශාල ම ජීවීන් හැටියටත්, සමාජශීලි හා බුද්ධිමත් සත්ත්ව විශේෂයක් හැටියටත්, අලි ඇතුන්ගේ සුවිශේෂ බවක් තිඛෙනවා. බටහිර චිත්රපට කණ්ඩායම් වැඩි අවධානයක් යොමු කරන්නේ අප්රිකානු අලියාටයි. ආසියානු අලි ඇතුන් ගැන චිත්රපට රූපගත කරන්නට වුවත් ඔවුන් තෝරා ගන්නේ ලංකාවට වඩා ඉන්දියාව, තායිලන්තය වැනි රටවල්. මා මීට පෙර වතාවක (2011 මාර්තු 13) පෙන්වා දුන් පරිදි සොබාදහම ගැන චිත්රපට නිපදවන විදේශීය කණ්ඩායම් මෙරටට ඇද ගන්නට අප තවමත් එතරම් උත්සාහයක් ගන්නේ නැහැ. ඉදහිට හෝ මෙහි එන විදෙස් චිත්රපට නිෂ්පාදකයන්ට හසු කර ගන්නට හැකි විසිතුරු සැබෑ කථා විශාල ප්රමාණයක් අප සතුව තිඛෙනවා. චාන්දනී චිත්රපටය එයට තවත් උදාහරණයක්.

මේ චිත්රපටය වනජීවීන් හෝ පරිසරය හෝ ගැන කථාවක් නොවෙයි. එය අවධානය යොමු කරන්නේ හීලෑ අලි ඇතුන් හා මිනිසුන් අතර සබදතාවයටයි. වාර්තා චිත්රපටයකට වඩා නාට්යමය හා රියැලිටි ස්වරූපයෙන් නිර්මිත මෙහි මිනිස් ‘චරිත’ තුනක් හමුවනවා.

කථා නායිකාව 16 හැවිරිදි චාන්දනී රේණුකා රත්නායක. ඇය පින්නවෙල අලි අනාථාගාරයේ ප්රධාන ඇත්ගොව්වා වන සුමනබණ්ඩාගේ දෙටු දියුණිය. සිට පිය පරම්පරාවේ සාම්ප්රදායිකව කර ගෙන ආ අලි ඇතුන් හීලෑ කර රැක බලා ගැනීමේ කාරියට අත තබන්නට ඇයට ලොකු ඕනෑකමක් තිඛෙනවා. පවුලේ පිරිමි දරුවකු නැති පසුබිම තුළ සුමනබණ්ඩා එයට එක`ග වී පරම්පරාගත දැනුම හා ශිල්පක්රම ටිකෙන් ටික චාන්දනීට උගන් වනවා. මේ සදහා කණ්ඩුල නම් අලි පැටවකු සොයා ගෙන එන ඔහු කණ්ඩුලගේ වගකීම් සමුදාය ක්රම ක්රමයෙන් චාන්දනීට පවරනවා.

ලංකාවේ අලි ඇතුන් පිළිබදව 1995දී පොතක් ලියූ ජයන්ත ජයවර්ධන කියන හැටියට අලින් හීලෑ කිරීමේ වසර තුන් දහසකට වඩා පැරණි සම්ප්රදායක් අපට තිඛෙනවා. වනගත අලින් අල්ලා, මෙල්ල කොට පුහුණු කළ හැකි වූවත් බල්ලන්, පූසන් වැනි ගෘහස්ත සතුන්ගේ මට්ටමට අලින් හීලෑ නොවන බවත් ඔහු කියනවා.

“ර්ගොඩබිම වෙසෙන දැවැන්ත ම සත්ත්වයා වන අලියාට විශාල ශරීර ශක්තියක් තිඛෙන නිසා ඔවුන් හැසිරවීම ප්රවේශමෙන්, සීරුවෙන් කළ යුක්තක්. අලි පුහුණුවට ආවේනික වූ වචන දුසිමක් පමණ යොදාගෙන මේ දැවැන්තයන්ට අණ දීමේ කලාවක් අපේ ඇත්ගොව්වන්ට තිඛෙනවා. එහිදී ඇත්ගොව්වා සහ අලියා අතර ඇතිවන සබදතාවය ඉතා වැදගත්.”

එම සම්ප්රදාය පිළිබද ඉගි කිහිපයක් අප චාන්දනී චිත්රපටයේ දකිනවා. අලි හසුරු වන බස් වහර, අලියාගේ සිරුරේ මර්මස්ථාන හා අලින්ගේ ලෙඩට දුකට ප්රතිකාර කිරීමට කැප වූ දේශීය සත්ත්ව වෙදකම් ආදීය එයට ඇතුළත්. අලි පුහුණු කිරීම හා මෙහෙයවීම ක්රමවේදයන් ගණනාවක සංකලනයක්. එයට දැනුම, ශිකෂණය, කැපවීම යන සියල්ල අවශ්යයි. චාන්දනීට මේ අභියෝග ජය ගත හැකිද යන්න පිරිමි ඇත්ගොව්වන්ට මෙන් ම ඇගේ අසල්වාසීන්ට ද ප්රශ්නයක්. කථාව දිග හැරෙන්නේ එයට චාන්දනී හා ඇගේ පියා ඉවසිලිවන්තව හා අධිෂ්ඨානයෙන් මුහුණ දෙන ආකාරය ගැනයි.

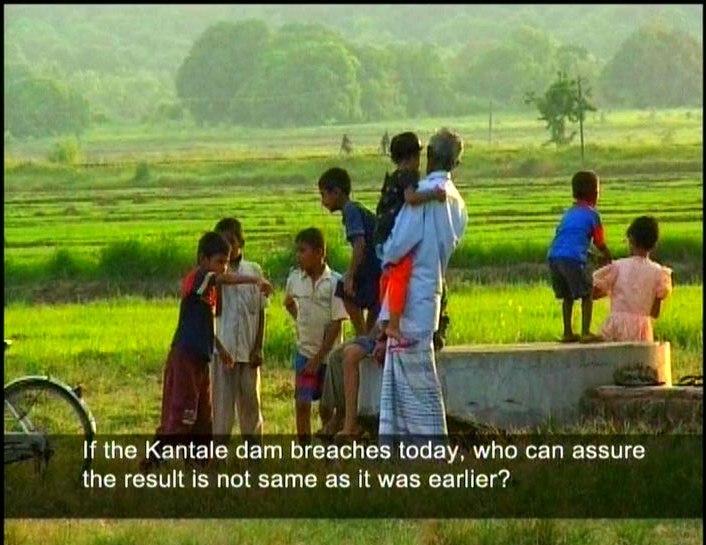

මෙහි දී චාන්දනීගේ මග පෙන්වීමට වනජීවී ෙකෂත්ර නිලධාරියකු වන මොහමඩ් රහීම් ඉදිරිපත් වනවා. මොහොමඩ් සමග උඩවලවේ ජාතික වනෝද්යානය හා ඒ අවට ගම්මානවල සංචාරය කරන චාන්දනී, වනගත අලි ඇතුන් මුහුණ දෙන ඉඩකඩ, ආහාර හා ජලය පිළිබද දැවෙන ප්රශ්න දැක ගන්නවා.

තදබද වූ මේ දූපතේ, සීමිත බිම් ප්රමාණයක් සදහා මිනිසුන් හා අලින් අතර පවතින නිරතුරු අරගලයෙන් වසරක් පාසා අලි 150ක් පමණත්, මිනිසුන් 50 දෙනකු පමණත් මිය යනවා. මේ අලි-මිනිස් ගැටුමට ඓතිහාසික, සාමාජයීය හා ආර්ථීක සාධක ගණනාවක් ඇතත් ඒවා විග්රහ කිරීමට මේ චිත්රපටය උත්සාහ කරන්නේ නැහැ. එබදු දැඩි අර්බුදයක් පසුබිමේ ඇති බව ප්රේකෂකයාට සිහිපත් කළත් එයට සරල පැලැස්තර විසදුම් ඉදිරිපත් කරන්නේත් නැහැ.

මේ චිත්රපටයේ මා දකින එක් ගුණයක් නම් මිනිසුන්ට වඩා අලි ඇතුන්ගේ ජීවිත වටිනා බව තර්ක කරන අන්තවාදී පරිසරවේදීන්ට එහි කිසිදු තැනක් නොදීමයි. ඒ වෙනුවට මිනිස් සමාජයට පිවිස යම් තරමකට හීලෑ බවක් ලැබූ අලි ඇතුන් සමග සානුකම්පිකව ගනුදෙනු කරන මානවයන් ද ලක් සමාජයේ සිටින බව මේ චිත්රපටය හීන්සීරුවේ ලෝකයට කියනවා. අවිහිංසාවාදය හා සාංස්කෘතික සාරධර්ම ගැන දේශනා කිරීමකින් තොරව එය ප්රායෝගිකව මේ දූපතේ සිදු වන හැටි රූපානුසාරයෙන් හා කථානුසාරයෙන් පෙන්වා දෙනවා.

අලින් හා මිනිසුන් අතර මිතුදම වෘතාන්ත චිත්රපට ගණනාවක ම තේමාව ලෙස මින් පෙරත් යොදා ගෙන තිඛෙනවා. සිනමාවේ මුල් යුගයේ උදාහරණයක් නම් 1937දී නිර්මාණය වූ Elephant Boy රුඩ්යාඩ් කිප්ලිංගේ ඔදදප්ස කථාව පදනම් කරගෙන තැනූ ඒ චිත්රපටයෙන් කියවුණේ කැලයේ අලින් සමග මිතුරු වන දරුවකු ගැනයි. හීලෑ කළ අලි ඇතුන් හා දරුවන් ගැනත් සිනමා සිත්තම් බිහි වී තිඛෙනවා. ජපන් ජාතික චිත්රපට අධ්යකෂක ෂුන්සාකු කවාකේ 2005දී නිර්මාණය කළ Hoshi ni natta shonen (Shining Boy and Little Randy) චිත්රපටයෙන් කියැවුණේ ඇත්ගොව්වකු වීමේ ආශාවෙන් තායිලන්තයට ගිය ජපන් දරුවකුගේ සැබෑ කථාවයි.

බොහෝ විට මෙබදු චිත්රපටවල ප්රධාන මිනිස් චරිතය වන්නේ පිරිමි ළමයෙක්. චාන්දනී වැනි දැරියක් මෙබදු කාරියකට ඉදිරිපත් වීම සැබෑ ලෝකයේ කොතැනක වූවත් අසාමාන්ය වීම මෙයට හේතුව විය හැකියි. ඉතිහාසය පුරා ම පිරිමින් පමණක් සිදු කළ වගකීමක් කාන්තාවකට පැවරීම හරහා සුමනබණ්ඩා සියුම් සමාජ විප්ලවයකටත් දායක වනවා. එහෙත් චාන්දනී චිත්රපටයේ අරමුණ එබදු මහා පණිවුඩ සන්නිවේදනය නොවෙයි. එය දැරියක හා අලි පැටවකු අතර ඇතිවන මිතුරුකම වටා ගෙතුණු විසිතුරු කථාන්තරයක්.

බොහෝ විට මෙබදු චිත්රපටවල ප්රධාන මිනිස් චරිතය වන්නේ පිරිමි ළමයෙක්. චාන්දනී වැනි දැරියක් මෙබදු කාරියකට ඉදිරිපත් වීම සැබෑ ලෝකයේ කොතැනක වූවත් අසාමාන්ය වීම මෙයට හේතුව විය හැකියි. ඉතිහාසය පුරා ම පිරිමින් පමණක් සිදු කළ වගකීමක් කාන්තාවකට පැවරීම හරහා සුමනබණ්ඩා සියුම් සමාජ විප්ලවයකටත් දායක වනවා. එහෙත් චාන්දනී චිත්රපටයේ අරමුණ එබදු මහා පණිවුඩ සන්නිවේදනය නොවෙයි. එය දැරියක හා අලි පැටවකු අතර ඇතිවන මිතුරුකම වටා ගෙතුණු විසිතුරු කථාන්තරයක්.

ලංකාවේ අලි ඇතුන් කණ්ඩායම් දෙකකට ඛෙදිය හැකියි. වනගත (වල්) අලි හා හීලෑ කළ අලි හැටියට. 2011 අගෝස්තුවේ පැවැත්වූ මුල් ම අලි ඇත් සංගණනයෙන් සොයා ගත්තේ වනගත අලි ඇතුන් 7,339ක් මෙරට සිටින බවයි. (රකෂිත ප්රදේශවල හෝ ඒවා ආසන්නයේ 5,879කුත් අනෙකුත් ප්රදේශවල තවත් 1,500කුත් වශයෙන්.) ඇතැම් පරිසරවේදීන් මේ සංගණනයේ ක්රමවේදය විවේචනය කළා. එහෙත් පරිපූර්ණ දත්තවලට වඩා කුමන හෝ දත්ත සමුදායක් ලබාගැනීම හරහා අලි සංරකෂණයට රුකුලක් ලැඛෙන බව සිතිය හැකියි.

අපේ රටේ හීලෑ අලි ඇතුන් සිය ගණනක් ද සිටිනවා. එමෙන්ම මේ දෙකොටසට අතරමැදි සංක්රමනීය තත්ත්වයේ අලි ඇතුන් ද සිටිනවා. ස්වාභාවික පරිසරයේ විවිධ හේතු නිසා මවු සෙනෙහස අහිමි වූ ලාබාල අලි පැටවුන්ට රැකවරණය දෙමින් ඔවුන් ලොකු මහත් කිරීමට පින්නවෙල අලි අනාථාගාරය ඇරඹුවේ 1975දී. මේ වන විට සියයකට ආසන්න අලි ඇතුන් සංඛ්යාවක් එහි නේවාසිකව සිටිනවා. දෙස් විදෙස් සංචාරකයන් අතර ජනප්රිය ආකර්ශනයක් බවට පත්ව ඇති මේ අනාථාගාරයේ, පශ= වෛද්යවරුන් හා සත්ත්ව විද්යාඥයන්ගේ අනුදැනුම ඇතිව අලි ඇතුන් බෝ කිරීමේ වැඩපිළිවෙලක් ද 1982 සිට ක්රියාත්මක වනවා. මීට අමතරව උඩවලවේ වනෝද්යානයට බද්ධිතව ඇත් අතුරු සෙවන නම් තවත් තැනක් ද පිහිටුවා තිඛෙනවා.

ලංකාවේ වෘතාන්ත චිත්රපටයක් නිපදවීමට සාමාන්යයෙන් යොද වන තරමේ මුදල් හා තාකෂණික ආයෝජනයක් මේ වාර්තා චිත්රපටයට වැය කරන්නට ඇතැයි අනුමාන කළ හැකියි. එහෙත් මේ ආයෝජනයේ උපරිම ඵල නෙළා ගන්නට එහි සංස්කරණය (editing) මීට වඩා කල්පනාකාරී හා නිර්දය ලෙස සිදු කළා නම් හැකි වන බව චිත්රපට මාධ්යයේ ශිල්පීය ක්රම දත් මගේ ඇතැම් මිතුරන්ගේ අදහසයි.

ආසියානු අලි ඇතුන් වනගතව හමුවන රටවල් අතරින් වැඩි ම අලි ඝනත්වය (highest Asian elephant density) ඇත්තේ ලංකාවේයි. මේ දූපතේ බිම් හා සොබා සම්පත්, මිලියන් 20කට වැඩි ජන සංඛ්යාවක් හා හත් දහසකට අධික අලි ඇතුන් ගණනක් අතර තුලනය කර ගන්නේ කෙසේද යන්න අප මුහුණ දෙන ප්රබල සංරකෂණ අභියෝගයක්. අලි ඇතුන් ගැන කථා කරන විට පරිසරවේදීන් බහුතරයක් ආවේගශීලී වනු දැකිය හැකියි. මෙරට ඉතිරිව ඇති වනාන්තර, තණබිම් හා විල්ලූ ප්රදේශවලට ස්වාභාවිකව දරා ගත හැකි අලි ඇතුන් සංඛ්යාව කොපමණ ද? ඒ සංඛ්යාව ඉක්මවා අලි ගහණයක් ඇති බව විද්යාත්මකව සොයා ගතහොත් අතිරික්තය ගැන කුමක් කළ හැකි ද – කළ යුතු ද? වනගත අලින්ට සමාන්තරව හීලෑ අලින් මනා සේ රැක බලා ගැනීම ඔස්සේ අලින් වද වී යාමේ තර්ජනය පාලනය කළ හැකි ද? මේ සියල්ල සංකීර්ණ ප්රශ්නයි.

ඒවාට පිළිතුරු සොයන්නට විද්යාත්මක ක්රමවේදයන් මෙන් ම අපේ සාරධර්ම ද යොදා ගත හැකියි. විසදුම් සොයා යන අතර අලි – මිනිස් සබදතාවයේ පැතිකඩ ගැන නිවැරදි, නිරවුල් සන්නිවේදනයක් දේශීයව මෙන් ම ජාත්යන්තරව ද කළ යුතුයි. ‘මිනී මරන අලි’ හා ‘අලි මරන මිනිසුන්’ ගැන සරල ත්රාසජනක වාර්තාවලින් ඔබ්බට යන තුලනාත්මක කථාබහකට අප යොමු විය යුතුයි. එමෙන් ම අලි – දිවි – වලසුන්ට සීමා නොවූ අතිශයින් විවිධ හා විචිත්ර ජීවි විශේෂ රාශියක් මේ දූපතේ අපත් සමග වෙසෙන බවත් අමතක නොකරන්න!