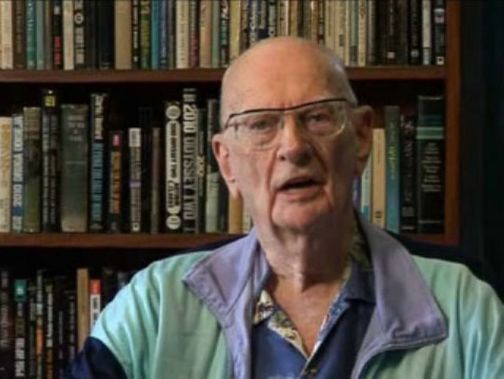

“Our teacher said our country is small and is surrounded by the sea….she showed it on the globe.”

With these words, young Lakshani Fernando (photo, above) begins telling us the compact story of her short life.

Lakshani, 9, has lived by the sea (Indian Ocean) from the time she was born. When she was just six, the Asian Tsunami of December 2004 destroyed their beachfront house in Koralawella, Moratuwa, on Sri Lanka’s western coast. More than three years later, when my colleague Buddhini Ekanayake met Lakshani in March 2008, the family was still struggling to raise their heads from that massive blow.

A day in Lakshani’s life is the story of a short, 3-minute film that Buddhini produced for TVE Asia Pacific a few weeks ago. It’s part of an Asian and African television co-production project that is about, for and by children.

In the film, Lakshani shares the highlights of a typical day. That includes going for a walk on the polluted beach with her fisherman father, spending a few hours at the nearby school and playing with neighbourhood children. While at it, she tells us her wishes for a cleaner beach and a better neighbourhood.

Buddhini called Lakshani a ‘Child of the Sea’. Even the cruel waves of the tsunami didn’t scare Lakshani away for too long.

“I love to play with waves…” Lakshani says towards the end of the film. Then she looks far out at the horizon, and talks again. “There are ships far out at sea. That’s all there is…”

She might not yet imagine lands beyond ships and waves, but last week, her story travelled across the seas. Over 500 broadcast media managers, journalists and researchers from around the world, who’d gathered in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, for Asia Media Summit 2008, had a glimpse of Lakshani when the first 90 seconds of the film was screened during plenary.

Elizabeth Smith, secretary general of the Commonwealth Broadcasting Association (CBA), chose an extract from Lakshani’s story to introduce the media initiative. Sitting in the audience, I immediately texted the news to Buddhini.

Watch “I am A Child of the Sea”:

This film forms part of a series that has 20 TV producers from 13 countries engaging in a co-production of a short programmes series (mini documentaries) about and for children. The series is the outcome of a regional project organised by the Asia Pacific Institute for Broadcasting Development (AIBD) in collaboration with the French Ministry of Foreign affairs, the Commonwealth Broadcasting Association (CBA), Thomson Foundation, Prix Jeunesse, Children and Broadcasting Foundation for Africa and RTM-IPTAR of Malaysia.

The project tries to capture cultural diversity through the eyes of children. When its concept first reached us, it was defined very narrowly in terms of ethnicity and/or religion. TVE Asia Pacific being a strictly secular organisation, we couldn’t fit into such a tight range. Besides, we realised that many modern day children have a self identity that goes above and beyond the race and religion that blind chance of birth assigned to them.

So we took an editorial decision: instead of doing a story that highlights factors that utterly and bitterly divide humanity (such as race and religion, both of which fuel the long-drawn war in Sri Lanka), we would look for a unifying factor. The tsunami’s killer waves, when they rolled in, didn’t care for our petty human divisions. For a few days and weeks following the tragedy, Sri Lanka was united in shock and grief in a manner I have never seen in my 42 years of living here. (Then we went back to killing each other again.)

The result of our search was Lakshani and her story captured in ‘I am a Child of the Sea’.

Buddhini chose to feature Lakshani after interviewing 10 children from different localities and a diversity of cultural backgrounds. (Never once did she ask for the child’s religion, which unlike ethnicity is not always apparent from the name.) There was some significance in featuring a child who identifies herself closely with the Sea in a country where tens of thousands of tsunami-affected people have still not come to terms with the sea. Even after the tsunami destroyed their home, Lakshani’s family moved to a ‘temporary’ shelter within sight of the sea. Thus, her story had a close association with the sea which formed part of her lifestyle, environment and culture.

Buddhini developed the script after several leisurely chats with Lakshani, based partly on the child’s own writing about herself. Filming the story took place in early March 2008, with the full consent of her parents, extended family and neighbours. Read more about the making of this film on TVEAP website and on Buddhini’s own blog.

Lakshani’s story is symbolic at another level. It reveals how, despite receiving a massive outpouring of donations from all over the world, some tsunami-affected families are still struggling to put together their shattered lives. The litany of woes, missed opportunities and sometimes outright plundering of donations came out strongly in the first hand accounts of affected people (in India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand) who spoke to us during the Children of Tsunami media project. Read our reflections on the project in Communicating Disasters book published in 2007.

Lakshani’s family is not typical of Sri Lanka’s tsunami affected persons. Unlike most such families, the Fernandos live on the western coast, relatively close to Colombo. Although wave action destroyed or damaged beachfront homes in these areas, most attention was focused on areas in the south, east and north of the island that were hit much harder. So those affected and living on the west coast have often been overlooked or dismissed lightly. In this sense, Lakshani’s family has some parallels with what I called ‘step-children of tsunami’.

There is a bit more cheerful post-script to this story. During several visits to Lakshani and family for researching, filming and editing this film, Buddhini (who has a daughter aged four herself) bonded with the girl. It became more than a mere film-making venture, and has led to a lasting relationship. Meanwhile, young voice artiste Shanya Fernando, who rendered Lakshani’s Sinhala voice into English for an international audience, has also felt an attachment to the ‘star’ of our film.

While the film was made with the informed consent of Lakshani’s family who received no material benefits for their participation, both Buddhini and Shanya have since presented some basic educational gifts to Lakshani — who is certainly in need of such help. And who am I to stand in the way of such gestures of human kindness?

Photos by Amal Samaraweera, TVE Asia Pacific

Cartoon from Daily Mirror, Sri Lanka

Cartoon from Daily Mirror, Sri Lanka