Indeed, an Avatar-like struggle is unfolding in the Amazon forest right now. The online campaigning group Avaaz have called it a ‘Chernobyl in the Amazon’. According to them: “Oil giant Chevron is facing defeat in a lawsuit by the people of the Ecuadorian Amazon, seeking redress for its dumping billions of gallons of poisonous waste in the rainforest.”

From 1964 to 1990, Avaaz claims, Chevron-owned Texaco deliberately dumped billions of gallons of toxic waste from their oil fields in Ecuador’s Amazon — then pulled out without properly cleaning up the pollution they caused.

In their call to action, they go on to say: “But the oil multinational has launched a last-ditch, dirty lobbying effort to derail the people’s case for holding polluters to account. Chevron’s new chief executive John Watson knows his brand is under fire – let’s turn up the global heat.”

In their call to action, they go on to say: “But the oil multinational has launched a last-ditch, dirty lobbying effort to derail the people’s case for holding polluters to account. Chevron’s new chief executive John Watson knows his brand is under fire – let’s turn up the global heat.”

Avaaz have an online petition urging Chevron to clean up their toxic legacy, which is to be delivered directly to the company´s headquarters, their shareholders and the US media. I have just signed it.

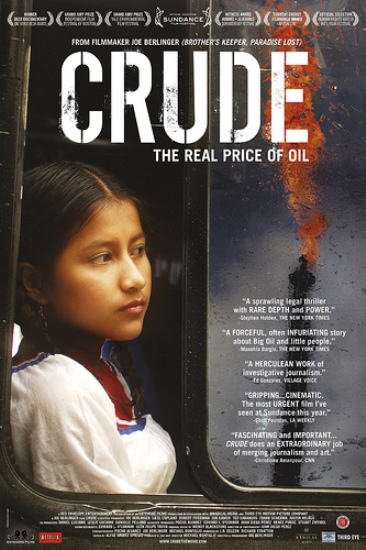

Others have been highlighting this real life struggle for many months. Chief among them is the documentary CRUDE: The Real Price of Oil, made by Joe Berlinger.

The award-winning film, which had its World Premiere at the 2009 Sundance Film Festival, chronicles the epic battle to hold oil giant Chevron (formerly Texaco) accountable for its systematic contamination of the Ecuadorian Amazon – an environmental tragedy that experts call “the Rainforest Chernobyl.”

Here’s the official blurb: Three years in the making, this cinéma-vérité feature from acclaimed filmmaker Joe Berlinger is the epic story of one of the largest and most controversial legal cases on the planet. An inside look at the infamous $27 billion Amazon Chernobyl case, CRUDE is a real-life high stakes legal drama set against a backdrop of the environmental movement, global politics, celebrity activism, human rights advocacy, the media, multinational corporate power, and rapidly-disappearing indigenous cultures. Presenting a complex situation from multiple viewpoints, the film subverts the conventions of advocacy filmmaking as it examines a complicated situation from all angles while bringing an important story of environmental peril and human suffering into focus.

Watch the official trailer of Crude: The Real Price of Oil

According to Amazon Watch website: “With key support from Amazon Watch and our Clean Up Ecuador campaign, people are coming together to promote (and see) this incredible film, and then provide ways for viewers to support the struggle highlighted so powerfully by the film.”

They go on to say: “A victory for the Ecuadorian plaintiffs in the lawsuit will send shock waves through corporate boardrooms around the world, invigorating communities fighting against injustice by oil companies. The success of our campaign can change how the oil industry operates by sending a clear signal that they will be held financially liable for their abuses.”

While Avatar‘s story unfolds in imaginary planet Pandora — conjured up by James Cameron’s imagination and created, to a large part, with astonishing special effects, the story of Crude is every bit real and right here on Earth. If one tenth of those who go to see Avatar end up also watching Crude, that should build up much awareness on the equally brutal and reckless conduct of Big Oil companies.

Others have been making the same point. One of them is Erik Assadourian, a Senior Researcher at Worldwatch Institute, whom I met at the Greenaccord Forum in Viterbo, Italy, in November 2009.

He recently blogged: “The Ecuadorians aren’t 10-feet tall or blue, and cannot literally connect with the spirit of the Earth (Pachamama as Ecuadorians call this or Eywa as the Na’vi call the spirit that stems from their planet’s life) but they are as utterly dependent—both culturally and physically—on the forest ecosystem in which they live and are just as exploited by those that see the forest as only being valuable as a container for the resources stored beneath it.”

Erik continues: “Both movies were fantastic reminders of human short-sightedness, one as an epic myth in which one of the invading warriors awakens to his power, becomes champion of the exploited tribe and saves the planet from the oppressors; the other as a less exciting but highly detailed chronicle of the reality of modern battles—organizers, lawyers, and celebrities today have become the warriors, shamans, and chieftains of earlier times.”