Today marks the 4th anniversary of the Indian Ocean Tsunami of December 2004.

The tsunami was triggered by a massive quake that erupted off the coast of Sumatra, and 6 miles deep under the Indian Ocean’s seabed. The estimated 9.1 to 9.3 magnitude earthquake was the strongest in 40 years and the fourth largest in a century. The U.S. Geological Survey later estimated that the amount of energy released was equivalent to the energy of 23,000 Hiroshima-type atomic bombs.

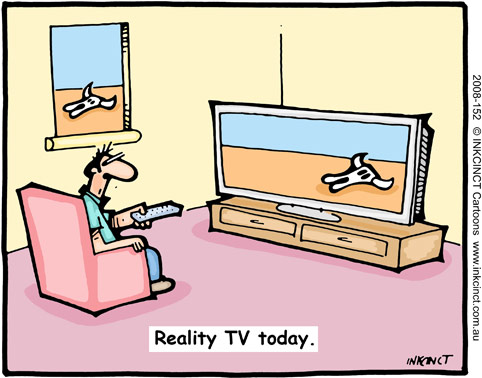

Despite a lag of up to several hours between the earthquake and the impact of the tsunami, nearly all affected people were taken completely by surprise. There were no tsunami warning systems in the Indian Ocean to detect tsunamis or to warn those living on the Indian Ocean rim areas. This cost the lives of over 225,000 people in 11 countries — many of who could have lived if only they had a timely warning to rush inland.

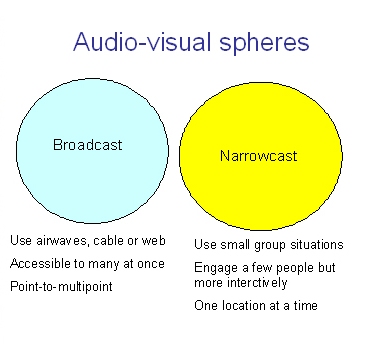

In the past four years, there have been various efforts to set up such early warning systems – as well as effective ways to deliver credible warnings to large numbers of people quickly. These are meant to provide 24/7 coverage to Indian Ocean countries in the same way the Pacific Tsunami Warning Centre has been covering Pacific Ocean countries for many years.

All this is necessary – but not sufficient – to guard ourselves against future tsunamis. For it’s not just earthquakes undersea that can trigger tsunamis. An asteroid impact could trigger the mother of all tsunamis that can impact coastal areas all over the planet.

An asteroid that struck the Earth 65 million years ago wiped out the dinosaurs and 70 per cent of the species then living on the planet. The destruction of the Tunguska region of Siberia in June 1908 – whose centenary was marked this year – is known to have been caused by the impact of a large extraterrestrial object.

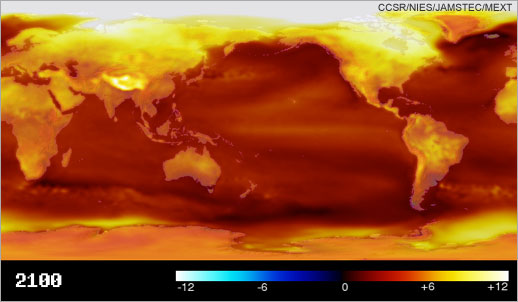

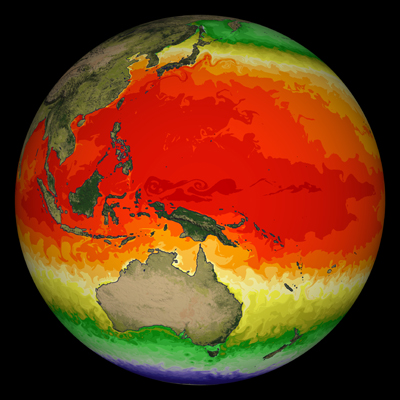

In fact, we should worry more. Duncan Steel, an authority on the subject, has done some terrifying calculations. He took a modest sized space rock, 200 metres in diameter, colliding with Earth at a typical speed of 19 kilometres per second. As it is brought to a halt, it releases kinetic energy in an explosion equal to 600 megatons of TNT — 10 times the yield of the most powerful nuclear weapon tested (underground). Even though only about 10 per cent of this energy would be transferred to the tsunami, such waves will carry this massive energy over long distances to coasts far away. They can therefore cause much more diffused destruction than would have resulted from a land impact. In the latter, the interaction between the blast wave and the irregularities of the ground (hills, buildings, trees) limits the area damaged. On the ocean, the wave propagates until it runs into land.

Scientists have been talking about asteroid impact danger for decades. Arthur C Clarke suggested – in his 1973 science fiction novel Rendezvous with Rama – that as soon as the technology permitted, we should set up powerful radar and optical search systems to detect Earth-threatening objects. The name he suggested was Spaceguard, which, together with Spacewatch, has now been widely accepted.

In November 2008, a group of the world’s leading scientists urged the United Nations to establish an international network to search the skies for asteroids on a collision course with Earth. The spaceguard system would also be responsible for deploying spacecraft that could destroy or deflect incoming objects.

The group – which includes the Royal Society president Sir Martin Rees and environmentalist Sir Crispin Tickell – said that the UN needed to act as a matter of urgency. Although an asteroid collision with the planet is a relatively remote risk, the consequences of a strike would be devastating.

Read more media coverage and commentary at:

The Guardian, 7 Dec 2008: UN is told that Earth needs an asteroid shield

World Changing, 10 Dec 2008: Giant asteroids and international security

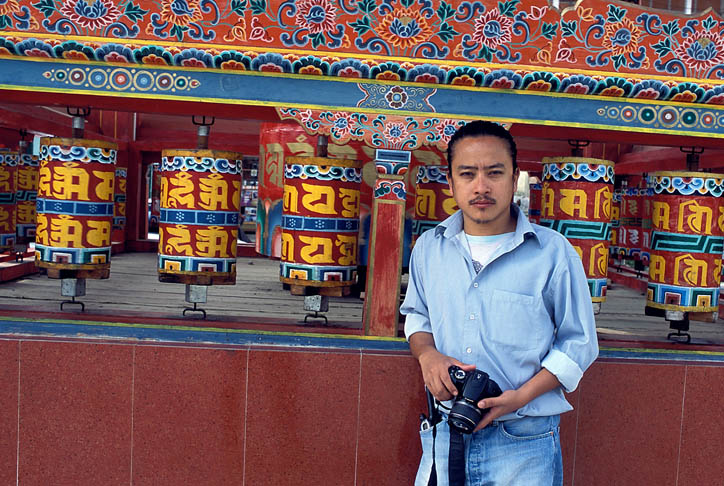

This is exactly the message in an excellent documentary called Planetary Defence made by Canadian filmmaker M Moidel, who runs the Space Viz production company. Over the past many months, the film has been screened at the United Nations, on various TV channels and at high level meetings of people who share this concern.

Its main thrust: Scientists and the military have only recently awakened to the notion that asteroid impacts with Earth do happen. Planetary Defense meets with both the scientific and military communities to study our options to mitigate an impact. It makes the pivotal point: “Civilization is ill prepared for the inevitable. It’s not if an impact will happen with the Earth, it’s when!”

In such an event, the film asks, who will save Earth? The 48 minute documentary explores the efforts underway to detect and mitigate an impact with Earth from asteroids and comets, collectively known as NEO’s (Near Earth Objects).

Watch the trailer of Planetary Defence on YouTube:

Neil deGrasse Tyson, Astrophysicist and Director, American Museum of Natural History, in New York, says: “Planetary Defense, the film, is a documentary that explores how ill-prepared we are to prevent our own extinction from asteroid and comet impacts. Filmmaker M Moidel interviewed all the right people, asked them all the right questions, and leaves the viewer scared for our future, but empowered to do something about it.”

Read more about the film at Space Viz Productions website

Although we have never met, I have been in email contact with M Moidel for several years. I know how deeply committed he is to each of his documentary projects. Working on incredibly tight budgets and performing multiple tasks on his own, this brilliant Canadian has made some eminently accessible, timely and captivating documentaries on ‘big picture’ topics such as the search for intelligent life in the universe, the future of space exploration and, of course, coping with asteroid impacts.

Sir Arthur C Clarke, interviewed on some of Moidel’s films, including Planetary Defence, has highly commended his efforts.

Sir Arthur, whose Sri Lankan diving school was destroyed by the 2004 tsunami, wrote a few days after the disaster:

“Contrary to popular belief, we science fiction writers don’t predict the future — we try to prevent undesirable futures. In the wake of the Asian tsunami, scientists and governments are scrambling to set up systems to monitor and warn us of future hazards from the sea.

“Let’s keep an eye on the skies even as we worry about the next hazard from the depths of the sea.”