Fair trade is gaining momentum worldwide. More products are coming within the scope of fair trade in more countries.

That’s certainly good news in a world full of exploitation, inequality and unfairness at various levels.

But are we, in the mass media whose business it is to gather and deliver news and information, yet part of this good news ourselves? In other words, isn’t it high time there was fair trade in international media products too?

This is the simple question I raised this week at the V Greenaccord International Media Forum on the Protection of Nature, held from 7 to 11 Novmeber 2007 at the historic Villa Mondragone in Frascati, some 20km southeast of Rome.

During the 3.5 day international gathering of journalists and scientists concerned about the environment, we had several speakers referring to fair trade in Europe and at a global level. As more consumers become aware of environmental and social justice considerations, they are doing something about it in their buying of goods that are fairly traded, we heard.

The Wikipedia describes fair trade as ‘an organised social movement and market-based model of international trade which promotes the payment of a fair price as well as social and environmental standards in areas related to the production of a wide variety of goods.’

The movement focuses in particular on exports from developing countries to developed countries, most notably handicrafts, coffee, cocoa, tea, bananas, honey, cotton, wine and fresh fruit.

Fair trade is all about creating opportunities for small scale producers in the developing countries to get organised and supply directly to consumers in different parts of the world. When they sell direct, with few or no intermediaries, they can earn three or four times more, and that money will enhance their incomes, living standards and societies.

Read more about fair trade at Oxfam website, Make Trade Fair

Fair trade is certainly a cherished ideal, but it’s mired in complex economic and political realities. The globalised march of capital, profit-maximising corporations and developed country farm subsidies are among many factors that make fair trade difficult to achieve.

Fair trade activists are well aware of these realities. Their success is built on connecting producers with individual consumers. The proliferation of new media – especially the Internet – has made it easier to sustain such communications.

But the fair trade movement is still largely rooted in goods, not services. In my view, this is necessary but not sufficient in a modern world economy where nearly two thirds of global GDP comes from the services sector. (The Wikipedia’s breakdown for global GDP is agriculture 4%; industry 32%; services 64%).

I can’t immediately find how much the print, broadcast and online media contribute to that 64%, but it must be significant in the media saturated world today. And certainly the flow of media products — text, audio, photographs, moving images, online content and derivatives of these — has become more globalised in the past two decades.

So why not begin to agitate for fair trade in media products when they cross borders? Why aren’t we practising fair trade in our own media industry even as we cover fair trade as a story in our editorial content?

I didn’t get a very clear answer from fair trade activists that I posed this question to this week. While agreeing with me that the same fair trade principles can be applied to the media sector, they acknowledged that each sector has its own dynamics and must develop realistic ways to accomplish fair trade.

So it’s up to us who produce, distribute and manage assorted media products to begin this transformation from within.

Let’s not kid ourselves about what we are taking on. As I wrote in a blog post in September 2007:

“In the media-rich, information societies that we are now evolving into, media and cultural products are an important part of our consumption — and therefore, more of these have to be produced. In the globalised world, more television and film content is being sourced from the majority world — or is being outsourced to some developing countries where the artistic and technical skills have reached global standards.

“But in a majority of these media production deals, the developing country film and TV professionals don’t enjoy any fair terms of trade or engagement. Their creativity and toil are being exploited by those who control the global flow of entertainment, news and information products.

“This is why the top talent in the global South become assistants, helpers and ‘fixers’ to producers or directors parachuting in to our countries to cover our own stories for the Global Village. Equitable payments and due credits are hardly ever given.”

In the same commentary, I added:

“Unfair trade in film and TV is also how the unsung, unknown creative geniuses contribute significantly to the development of new cartoon animation movies or TV series, as well as hip video games that enthrall the global market. Lacking the clout and skill to negotiate better terms, freelancers and small companies across the global South remain the little elves who toil through the night to produce miracles. They work for tiny margins and even tinier credit lines. Some don’t get acknowledged at all.”

Read my blog post: Wanted: Fair trade in film and television!

Raising this amidst 60 journalists and producers from Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean attending the annual Greenaccord meeting, I pointed out that many of us were keen to contribute to media outlets beyond the countries where we are based. It gives us a chance to tell our stories to a bigger audience, and to have our voices heard about a range of issues and topics important to our communities.

And yes, the additional income that such work brings in is quite useful too, thank you.

Heads were nodding when I pointed out how hard it is for a talented, hard working journalist based in the majority world to break into the tightly controlled international media outlets. Even when they make an occasional breakthrough, they are often exploited by being paid lower professional fees for the same output and quality of work.

Or worse, majority world journalists are slighted and insulted for being where they are and who they are, rather than be judged on the merit of their work. As I wrote in a commentary published by SciDev.Net in November 2005: “Media gatekeepers in the North often dismiss the better-informed and equally competent Southern professionals — saying, insultingly, that ‘they don’t have the eye’! And for years, I have resisted the widespread practice of Northern broadcasters and filmmakers using the South’s top talent merely as ‘fixers’ and assistants.”

All this makes it imperative for us in the globalised media — in the developed North and developing South — to begin agitating for fair trade in media products and services. As in other products, we are not looking for charity or tokenism or a lowering of standards. We must strive for fairness and equality while working on building the capacity of southern journalists to generate world class media products.

And as my friend Darryl D’Monte — whom we missed dearly at this year’s Greenaccord forum — has been saying for years, publishing each other’s stories is one great step forward.

Mahatma Gandhi put it this way: we must be the change we wish to achieve.

Note: My own organisation, TVE Asia Pacific, practises what I preach here, and always engages local camera crews when we film TV stories across Asia. We will be taking up Fair Trade in Film and Television (FTinFT) as a campaign from 2008.

Read other related blog posts:

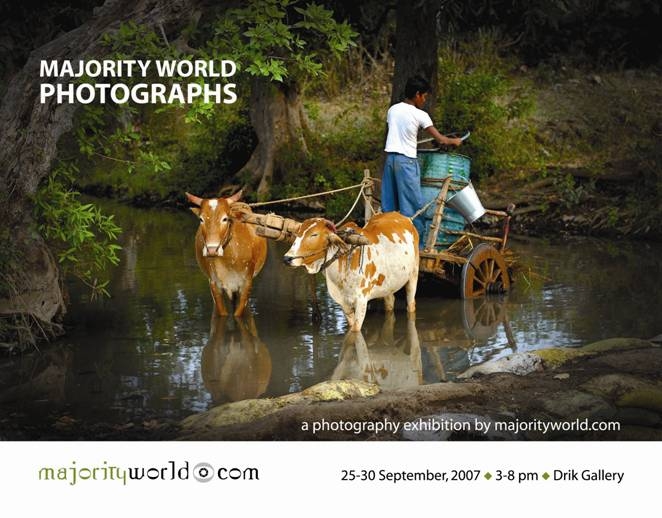

Images from the Majority World: Global South telling its own stories

Wanted: Fair trade in film and television!

Image of camera crews courtesy Pamudi Withanaarachchi of TVEAP.

Meeting photos courtesy Adrian Gilardoni’s Flickr account

Cartoon from Daily Mirror, Sri Lanka

Cartoon from Daily Mirror, Sri Lanka