In an earlier post, I wrote about how citizen groups are increasingly empowering themselves with information to demand greater accountability from their elected representatives in local, provincial and central governments.

This is collectively called Social Accountability – and it represents a significantly higher level of citizen engagement than merely changing governments at elections or taking to the streets for popular revolt (‘people power’).

In 2004, TVE Asia Pacific produced a half-hour international TV documentary titled People Power that profiled four Social Accountability projects in Africa (Malawi), Asia (India), Europe (Ireland) and Latin American (Brazil).

Watch the Brazil story on TVEAP’s YouTube channel:

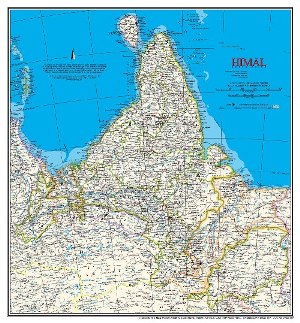

The experiment with participatory budgeting in the municipality of Porto Alegre in Brazil is a long-running example that we filmed. This is one of the largest cities in Brazil, one of the most important cultural, political and economic centers of Southern Brazil.

The city is well known as the birth place of the World Social Forum. The first WSF was held there in January 2001.

Participatory budgeting goes back to a decade earlier. It was started in 1989 by the newly elected “Worker Party” (PT) to involve people in democratic resource management in an effort to provide greater levels of spending to poorer citizens and neighborhoods. It has since spread to over 80 municipalities and five states in Brazil.

Porto Alegre’s challenge was how to include the poorer people in this success. Housing was a major problem as rural people migrate to the city looking for work. In the past, people built temporary houses on whatever land they could find, and the city council kept on demolishing these unauthorised structures.

As Brazil moved from a totalitarian to democratic form of government in the late 1980s, the newly elected city government adopted a program where the people participate in prioritising the City Budget.

The city is divided into sixteen regions and during each year, local neighbourhoods send representatives to people’s assemblies. In these assemblies, the neighbourhood representatives discuss priorities for the allocation of the city budget. They then elect their representatives from each region to form a budget council.

Over a year, from neighbourhood associations to people’s assemblies, up to 20,000 people have a direct say on how the city budget should be allocated.

This participation ensures democratic accountability and fairer distribution of tax revenue. It allows the poorest and the richest regions to have equal weight in the decision process.

After the introduction of participatory budgeting, an influential business journal nominated Porto Alegre as the Brazilian city with the ‘best quality in life’ for the 4th consecutive times. Statistics show that there has been significant improvement in quality of roads, access to water services, coverage of sewerage system, school enrollment and tax revenue collection.

We interviewed Joao Verle (wearing pink shirt in photo above), the then Mayor of Porto Allegre, who said: “I believe in this project since i was one of those responsible for starting it fifteen years ago. The participatory budget is now part of the organic life of this city – people can change it any time they please. And this makes it more adaptive to the people’s needs.”

First broadcast on BBC World in February 2004, People Power documentary has since been widely distributed to broadcast, civil society and educational users in the global South. It is still available from TVEAP on DVD and VHS video.

Photos are all captured from People Power video film. Courtesy TVE Asia Pacific

Read my post about social accountability in the world’s largest democracy, India