My post last week on the Maldives on the frontline of climate change reminds me that I have been covering this story for the better part of 20 years. I have just located this photo from the depths of my personal image collection.

I first visited the Maldives in 1988, which was within months of the Indian Ocean archipelago nation suffering from a massive storm surge in 1987. Although the damage was minimal, the experience was a forceful reminder of how vulnerable the Maldives can be to even a small rise in sea levels – this is what prompted the low lying nation to take up the issue internationally.

In November 1989, the Maldives hosted the first ever small states conference on sea level rise, held at the Kurumba island resort.

It was also one of the earliest international gatherings on this issue, which was to gain public interest and momentum in the years that followed. Among the participants were delegates from practically all the small states in different parts of the world (defined as those with less than 1 million population), and scientists from disciplines such as oceanography, climatology, meteorology and geology.

This was one of the first international scientific events that I covered as an eager young science journalist. I was then a roving South Asian correspondent for Asia Technology, a popular monthly on Asian science and technology published from Hong Kong (which, alas, folded up in 1991) – there’s nothing online as it was in the pre-web era!

The conference had technical sessions where experts debated scenarios and implications, and a political segment where delegations made their official statements. In the end, they issued the Malé Declaration on Global Warming and Sea Level Rise, which urged for inter-governmental action on the issue.

Some 18 years later, I’m still eager but not so young – and I’ve covered more than my share of international environmental conferences to know that they can’t save the world. At least not on their own.

But many serve a useful function in rallying around concerned parties, helping them to agree on advocacy positions. Progress at inter-governmental level can be painfully slow and incremental. Sustaining public and media interest is one way to keep pressure on the endlessly bickering governments.

Following the November 1989 conference, small island states played a key role in negotiations that led to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change adopted in 1992. This is the precursor to Kyoto, Bali and other processes that are now very much in the news.

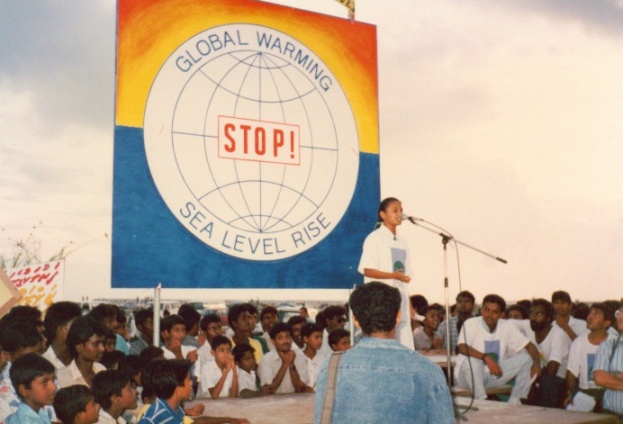

The Maldivian hosts knew that scientists and officials alone could not send out a powerful message to the world on what climate change means to low lying islands of the world – many of them no more than a few feet above sea level.

So on the last day evening, we were all taken to the Maldivian capital of Male, where we saw a demonstration and meeting held by the school children and ordinary people. To me, at least, this was the most striking moment of the whole week.

Leading up to this, I had been listening to competent experts and concerned officials talk about impacts, scenarios and mitigation measures for several days. Based on my notes and interviews, I filed several stories that captured highlights.

But unless I go back to my personal archives and look up those stories, I can no longer remember what I wrote. My lingering memories of this event are in these images, showing school children telling delegates – and the world – what it means to be living on the front lines of climate change impact.

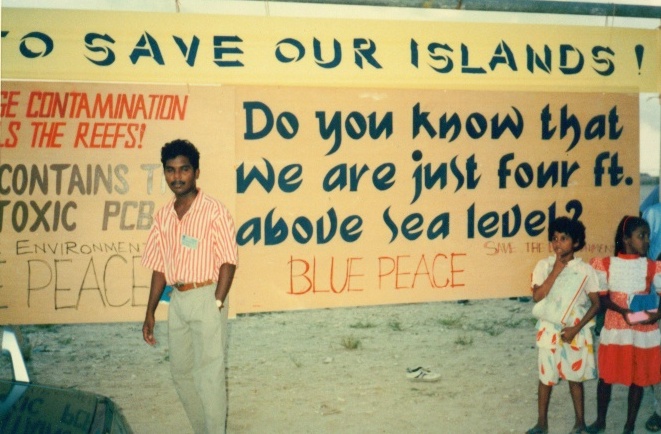

Then newly formed Maldivian environmental organisation Bluepeace was also part of the demonstration:

I worked for several years as a science and technology reporter. I was trained to gather, process and present facts and, preferably, expert opinion. But over the years I have realised that while hard facts and expert opinions are necessary, these tell only one part of complex stories we cover.

We need to bring in the human face of our stories — how ordinary children, women and men feel about issues and how they react to situations. This is why I now argue that we should not allow the human face of climate change to be lost in our well-meaning technical and economic discussions about climate change mitigation and adaptation.

We can cover carbon neutrality, zero emissions and common but differentiated responsibilities for all we like, but if we don’t pause to listen to these little voices from the waves – from the frontlines that are already feeling the heat – we will miss the bigger picture of what climate change is all about.

Dec 2007: Road to Bali – Beware of ‘Bad Weather Friends’

Photos by Nalaka Gunawardene, Male island, November 1989