“It was very sad when my daughter died of malaria at the age of four,” she recalls. What makes it especially tragic is the fact that malaria is a new arrival in her area.

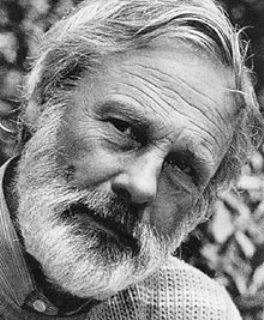

Nelly, 51, is a farmer living in Kenya’s Kericho District. Located high in the mountains, Kericho’s cold weather has kept mosquitoes at bay for centuries. But not any longer: global warming has raised the area’s average temperature, and mosquitoes have appeared in recent years, bringing malaria with them.

“I had never seen a mosquito until I was 20 years old. But now they are everywhere – people are even dying of malaria, something that was virtually unheard of 20 or 30 years ago,” Nelly told the 7th Greenaccord International Media Forum on the Protection of Nature, being held in Viterbo, Italy, 25 – 29 November 2009.

The theme this year is ‘Climate is changing: stories, facts and people’. Nelly Chepkoskei is one of 10 Climate Witnesses who travelled to the historic city from far corners of the world to share their stories of ground level changes induced by climate change.

Climate Witness is a global programme by WWF International to enable grassroots people to share their story of how climate change affects their lives and what they are doing to maintain a clean and healthy environment. All Climate Witness stories have been authenticated by independent scientists.

Married with five children, Nelly grows maize and tea, and keeps a few cows – the pride and joy of Kenyan farmers. Lacking faith in politicians and government, she is working with women in her community to pursue their own development.

Life was never easy, but climate change is making it even harder.

“Rainfall patterns have changed drastically in recent decades,” she says. “In the Kericho district, we used to have rain throughout the year. I remember clearly that my family celebrated Christmas when it was raining heavily. But today, Christmas is usually dry.”

“Rainfall patterns have changed drastically in recent decades,” she says. “In the Kericho district, we used to have rain throughout the year. I remember clearly that my family celebrated Christmas when it was raining heavily. But today, Christmas is usually dry.”

Unlike 20 years ago, the dry season is now hotter, drying up all the grass. In the past, the grass would remain green throughout the year.

“This means there isn’t enough fodder for my cows, leading to a drop in milk production and my income,” she explains. “The soils are also left bare during the dry season, which means more erosion when rains come in.”

With higher temperatures, more pests have turned up to damage crops. This prompts farmers to use more pesticides, increasing production costs and polluting the environment with hazardous chemicals.

Nelly turned out to be the most outspoken Climate Witness in Viterbo. In a frank exchange with an audience of 130 journalists, activists and scientists drawn from 55 countries, she exclaimed: “Don’t talk to politicians – they are the same everywhere! I can’t understand why journalists always follow politicians and are so keen to talk to them!”

She continued: “There is so many good things happening in Africa, but we don’t see it reported in the local and international media. You only hear about fighting, famine and corruption. So we continue to be seen and known as the Dark Continent.”

In her view, what Africa needs more than anything else is education. She firmly believes that higher levels of literacy and education would reduce the incidence of conflict and plunder.

Nelly herself is a high school drop out, and places a very high value on education to empower all Africans, especially women.

“There is a big gap between Kenyan intellectuals and the ordinary people. Knowledge is not where and how it is needed,” she says.

I asked her what she thought of foreign aid to Kenya and rest of Africa. This elicited a passionate and emphatic response: “If you want to spoil and corrupt Africa more, then keep giving aid to our governments. Aid money mostly ends up in the wrong hands, or buying guns to fight each other.”

I asked her what she thought of foreign aid to Kenya and rest of Africa. This elicited a passionate and emphatic response: “If you want to spoil and corrupt Africa more, then keep giving aid to our governments. Aid money mostly ends up in the wrong hands, or buying guns to fight each other.”

She added: “We do need help, but don’t give aid to our governments. Instead, support NGOs who are better in delivering to the grassroots.”

Nelly and her network of women are digitally empowered. They refer the web to find out information on what aid and opportunities are available and then pursue them with all available means. Armed with the latest data, they lobby local and provincial governments to ensure that aid pledged from international donors reach the intended communities.

Nelly may not be Wangari Maathai, the Kenyan environmentalist and women’s right activist, but she admits to being a Wangaari in spirit. And having listened to the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize at a previous Greenaccord forum, I readily agree: women like Nelly are a beacon of hope not just for Africa, but to the entire Majority World.

If only the mosquitoes could spread their passion and concern for the land and people…

Read WWF report on climate change impacts in East Africa

Images courtesy Greenaccord and WWF

“The Earth Journalism Awards were established to boost climate change coverage in this critical year leading up to Copenhagen, and to highlight the efforts of journalists reporting on this challenging subject around the world,” says

“The Earth Journalism Awards were established to boost climate change coverage in this critical year leading up to Copenhagen, and to highlight the efforts of journalists reporting on this challenging subject around the world,” says