This is a view of Colombo’s main cemetery, the final resting place for many residents of Sri Lanka’s capital and its suburbs. I took this photo less than a month ago, when I visited a grave on a quiet morning.

The late Bernard Soysa, a leading leftist politician and one time Minister of Science and Technology, once called it ‘the only place in Colombo where there is no discussion or debate’.

This afternoon, family, friends and many sorrowful admirers of Lasantha Wickramatunga, the courageous Sri Lankan newspaper editor who was brutally slain last week in broad daylight, took him there — and left him behind amidst the quiet company.

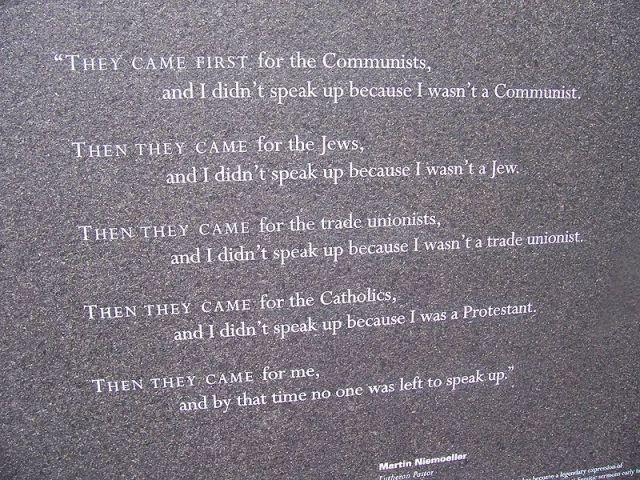

But not before making a solemn pledge. All thinking and freedom-loving people would continue to resist sinister attempts to turn the rest of Sri Lanka into a sterile zombieland where there is no discussion and debate. In other words, rolling out the cemetery to cover the rest of the island.

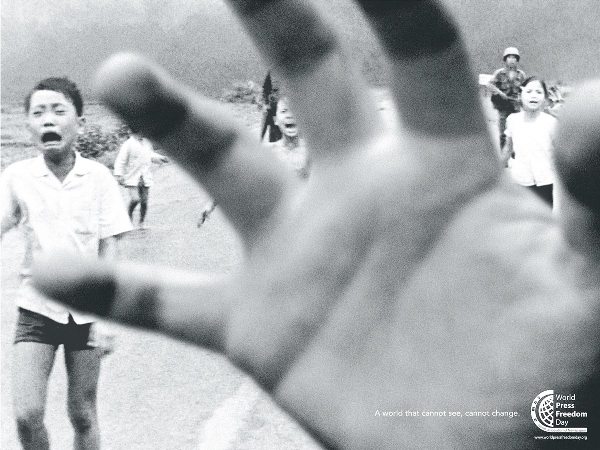

Rex de Silva, the first editor that Lasantha worked for (at the now defunct Sun newspaper) in the late 1970s, has just cautioned that Lasantha’s murder is the beginning of ‘the sound of silence’ for the press in Sri Lanka. Can this sound of silence be shattered by the silent, unarmed majority of liberal, peace-loving Lankans who were represented at the funeral service and the Colombo cemetery today?

And would they remember for all time Edmund Burke’s timeless words: “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing”?

How many would actually read, absorb and heed the deeply moving words of Lasantha’s one last editorial, copies of which were distributed at the cemetery and the religious service before that?

That editorial, which appeared in The Sunday Leader on 11 January 2009, embodies the best of Lasantha Wickrematunga’s liberal, secular and democratic views.

As I wrote in another tribute published today by Himal Southasian and Media Helping Media: “I have no idea which one – or several – of his team members actually penned this ‘Last Editorial’, but it reads authentic Lasantha all over: passionate and accommodating, liberal yet uncompromising on what he held dear. I can’t discern the slightest difference in style.”

“And there lies our hope: while Lasantha at 51 lies fallen by bullets, his spirit and passion are out there, continuing his life’s mission. That seems a good measure of the institutional legacy he leaves behind. If investigative journalism were a bug, the man has already infected at least a few of his team members…”

Read the full story of The Sunday Leader team’s courage under fire

Read The Sunday Leader‘s tribute to its founding editor on 11 January 2009: Goodbye Lasantha

Much has been written and broadcast in the past 100 or so hours since Lasantha’s journey was brutally cut short by as-yet-unidentified goons who have no respect for the public interest or have no clue how democracies sustain public discussion and debate. I’m sure more will be written – some in outrage and others in reflection – in the coming days and weeks.

Siribiris represents Everyman, who is repeatedly hoodwinked and taken for granted by assorted politicians and businessmen who prosper at the common man’s expense. The only way poor, unempowered Siribiris can get back at them is to puncture their egos and ridicule them at every turn. And boy, does he excel in that!

It’s no surprise that Lasantha – the bête noire of shady politicians and crooked tycoons – was very fond of Siribiris. Perhaps he saw his own life’s work as extending that of Siribiris in the complex world of the 21st century. That he did it with aplomb and gusto – and had great fun doing it, sometimes tongue stuck out at his adversaries – will be part of Lasantha’s enduring legacy. (As his last editorial reminded us, in 15 years of investigative journalism on a weekly basis, no one has successfully sued the newspaper for defamation or damages.)

So Goodbye, Lasantha. And Long live Siribiris!