Almost 70 years later, at the end of my own 30-year-long war, I have been reading and re-reading September 1, 1939. I’m trying to make sense of what is happening around me. The near hysterical mass euphoria on one side, and bewildered dejection on the other.

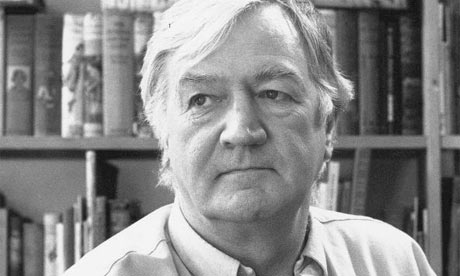

I was just six when the poet W H Auden died, and only 13 when this bloody, protracted war started. As I wrote in an essay published on the day after the war ended, I have lived all my adult years with this war providing a constantly grim, sometimes highly disruptive backdrop.

I survived the war in its various phases, including uneasy lulls when guns were temporarily silent. I watched most of my own friends join the exodus of genes and talent from a land where they saw no hope or future. I chose to stay on, but questioned the wisdom of it each time a major atrocity took place. I went through six jobs and one marriage, and raised a child who would soon be the same age as I was when the war started.

Are we at the end of the long, dark tunnel? Is the promised land of peace and prosperity now at hand? Have we seen the last of multi-barrel guns, grenade launchers, helicopter gunships, claymore mines and the deadly suicide bombers? Or will national security and anti-terrorism continue to dictate what we can or cannot do as citizens in a free, democratic and finally peaceful country?

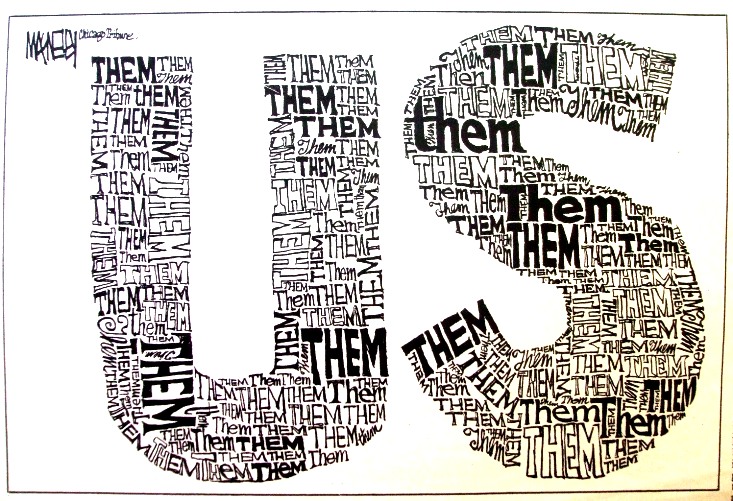

I honestly don’t know. Probably it’s too early to tell. But I’m uneasy with celebrations when so much healing and rebuilding need to be done. I’m worried about continuing the simplistic division of people into patriots and traitors. As I wrote earlier this week, this perception of Us and Them is our first landmine on the long road to peace. I don’t know why we as a people continue to insist on everything being in black and white. What happened to the myriad shades of grey?

For some months now, I’ve been turning to classical and modern poems for solace and comfort. When prose fails, verse must take over. Auden himself disliked this poem, but few words in English move me as his line: “We must love one another or die.”

So here it is, the full and original words of September 1, 1939 – for whatever resonance it may offer us across the gulf of seven decades straddling two centuries:

September 1, 1939

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.

Accurate scholarship can

Unearth the whole offence

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad,

Find what occurred at Linz,

What huge imago made

A psychopathic god:

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

Exiled Thucydides knew

All that a speech can say

About Democracy,

And what dictators do,

The elderly rubbish they talk

To an apathetic grave;

Analysed all in his book,

The enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain,

Mismanagement and grief:

We must suffer them all again.

Into this neutral air

Where blind skyscrapers use

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man,

Each language pours its vain

Competitive excuse:

But who can live for long

In an euphoric dream;

Out of the mirror they stare,

Imperialism’s face

And the international wrong.

Faces along the bar

Cling to their average day:

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.

The windiest militant trash

Important Persons shout

Is not so crude as our wish:

What mad Nijinsky wrote

About Diaghilev

Is true of the normal heart;

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

From the conservative dark

Into the ethical life

The dense commuters come,

Repeating their morning vow;

“I will be true to the wife,

I’ll concentrate more on my work,”

And helpless governors wake

To resume their compulsory game:

Who can release them now,

Who can reach the deaf,

Who can speak for the dumb?

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

– W. H. Auden