“MY NAME is Mohammed Sokor, writing to you from Dagahaley refugee camp in Dadaab. Dear Sir, there is an alarming issue here. People are given too few kilograms of food. You must help.”

This short, urgent message of a single individual has already joined the global humanitarian lore. It was sent by SMS (a.k.a. mobile texting) from the sender’s own mobile phone to the mobiles of two United Nations officials, in London and Nairobi. Sokor found these numbers by surfing at an internet café at the north Kenyan camp.

The Economist used this example to illustrate how the information dynamics are changing in humanitarian crises around the world. In an article on 26 July 2007, titled ‘Flood, famine and mobile phones’, it noted:

“The age-old scourge of famine in the Horn of Africa had found a 21st-century response; and a familiar flow of authority, from rich donor to grateful recipient, had been reversed. It was also a sign that technology need not create a ‘digital divide’: it can work wonders in some of the world’s remotest, most wretched places.”

Elsewhere in the article, it added: “Disaster relief is basically a giant logistical operation. Today’s emergency responders can no more dispense with mobile phones or electronically transmitted spreadsheets than a global courier company can. But unlike most couriers, aid donors operate amid chaos, with rapidly changing constraints (surges of people, outbreaks of disease, attacks by warlords). Mobile phones increase the flow of information, and the speed at which it can be processed, in a world where information used to be confused or absent. The chaos remains, but coping with it gets easier.”

Image courtesy WikiMedia

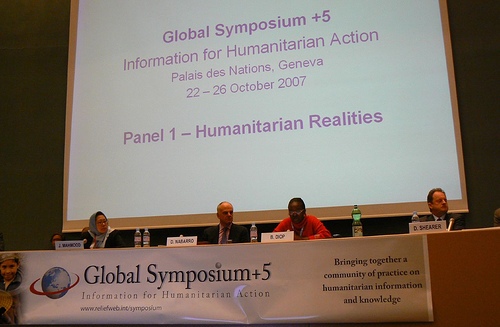

All available indicators suggest that the future of humanitarian assistance is going to be largely dependent on mobile communications. Despite this reality, old habits die hard. I sat through an entire presentation on ‘Innovation to Improve Humanitarian Action’ at the Global Symposium+5 on ‘Information for Humanitarian Action’ in Geneva this week — and not once did I hear mobile phones being mentioned. A group of 15 – 20 people had deliberated for 2 days to come up with their vision of ‘the potential of emerging technologies and approaches used in the field and globally to strengthen information sharing, coordination and decision-making’ in humanitarian work.

It might be that aid workers are all frustrated computer geeks…because all their talk was about collaborative and networking software, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), the use of really high resolution (read: oh-so-sexy) satellite imagery, and the latest analytical tools — all requiring high levels of skill and personal computers with loads of processing power.

But no mobile phones! This was too much to let pass, so I raised the question: did you guys even consider this near ubiquitous, mass scale technology and its applications in crisis and disaster situations? And how do you engage the digitally empowered, better informed disaster survivors and crisis-affected communities?

I also recalled the example of Aceh tsunami survivors keeping each other informed about the latest arrivals of relief supplies – all through their mobile phones (as cited by the head of MERCY Malaysia on the previous day).

It turned out that they did discuss mobiles — well, sort of. Amidst all the gee-whiz talk about high tech gadgets, I received a short answer: widespread as mobile phones now are, ‘these systems are not fully integrated or compatible with other information platforms’ — whatever that means! The group’s spokespersons also pointed out that since mobile services are all operated by commercial (telecom) service providers, using their networks involves lots of ‘negotiations’. (I would have thought it’s the same with those who operate earth-watching or communications satellites.)

The message I heard was: mobile phones are probably too down-market, low-tech and entirely too common for the great humanitarian aid worker to consider them as part of their expensive information management systems. For sure, everybody uses them to stay in touch in the field, but what use beyond that?

What uses, indeed. If today’s aid workers ignore the mobile phone revolution sweeping Africa, Asia Pacific and, to a lesser extent, Latin America, they risk marginalising their own selves. The choice seems to be: go fully mobile, or get lost.

Fortunately, the panel discussion that followed — on ‘Envisioning the Future’ — partly redressed this imbalance. The panel, comprising telecom industry, citizen media and civil society representatives, responded to the question: what will our humanitarian future look like and what role will information play in supporting it?

Leading the ‘defence’ of mobiles was Rima Qureshi, head of Ericsson Response, part of the global mobile phone manufacturer’s social responsibility initiatives. She reminded us there were now 3.4 billion (3,400 million) mobile phones in the world — and it was growing at 6 new mobile connections every second. By the time she ended her 8-minute talk, she said, some 3,000 new mobiles would have been connected for the first time.

This represents a huge opportunity, she said, to put information into everyone’s hands whenever and wherever they need it. And mobiles are all about two-way communication.

The new generation of mobile phones now coming out are not locked into a single telecom network, and have built-in global positioning (GPS) capability. This means the phone’s location can be pinpointed precisely anywhere on the planet — which can be invaluable in searching for missing persons in the aftermath of a disaster.

Wearing her Ericsson prophet’s hat, Rima said: “Everything we can do on a personal computer will soon become possible on a mobile. Mass availability of mobile phones, able to connect to the global Internet, will represent a big moment for human communication.”

And not just Ericsson, but many other mobile phone makers and network operators are rolling out new products and services. The new mobiles are easier to use, more versatile and durable, and come with longer-lasting or renewable sources of power. Wind-up phone chargers have been on the market for some years, and some new mobile phones come with a hand-cranking charging device that makes them entirely independent of mains electricity. With all this, the instruments keep getting cheaper too.

And if aid workers ignore these and other aspects of mobile realities, they shouldn’t be in their business!

Rima described another Ericsson initiative called Communication for All. It’s trying to harness the power of shared network, across commercial telecom operators and networks (but with some development funding from the World Bank) to deliver coverage to rural areas that aren’t as yet covered fully. The rolling out of coverage would have profound implications for disaster managers and aid workers.

As James Darcy, Director of humanitarian aid policy at the UK’s Overseas Development Institute, noted from the chair, the future of humanitarian communication is already here — but the sector needs to have more imagination in applying already available technologies for new and better uses.

My colleague Sanjana Hattotuwa, ICT researcher and activist from Sri Lanka, made the point that 3.4 billion mobiles raise new ethical considerations. For example, while it is now technologically possible to track the movement of every mobile phone – and therefore, in theory, each unit’s owner – this knowledge can be abused in the wrong hands. (I’ll write a separate blog post on Sanjana’s other remarks.)

Not everyone in the audience was convinced about the future being mobile. Soon enough, the predictable naysayer popped up: saying only 2.4 per cent of people in Sub-Saharan Africa as yet owned mobile phones, and Internet access was limited to only one per cent. Blah, blah, blah! (I was half expecting someone to blurt out the now completely obsolete – but sadly, not fully buried – development myth that there are more phones in New York city than in the whole of sub-Saharan Africa. That didn’t happen.)

Funny thing was, we were discussing all this at the Palais des Nations, the European headquarters of the UN, which is just literally across the street from the headquarters of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the authoritative monitor of telecom and ICT industry data and trends! It seemed that the gulf between some humanitarian workers and the telecom industry was much bigger than that.

Of course, being connected – to mobile, satellite and every other available information network – is only the first step. We can only hope humanitarian workers don’t end up in this situation, captured in one of my all-time favourite ICT cartoons (courtesy Down to Earth magazine):

Read about Sri Lanka’s pathfinding action research by LIRNEasia and others: Last Mile Hazard Information Dissemination Project

All Geneva photos courtesy UN-OCHA Flickr on Global Symposium+5