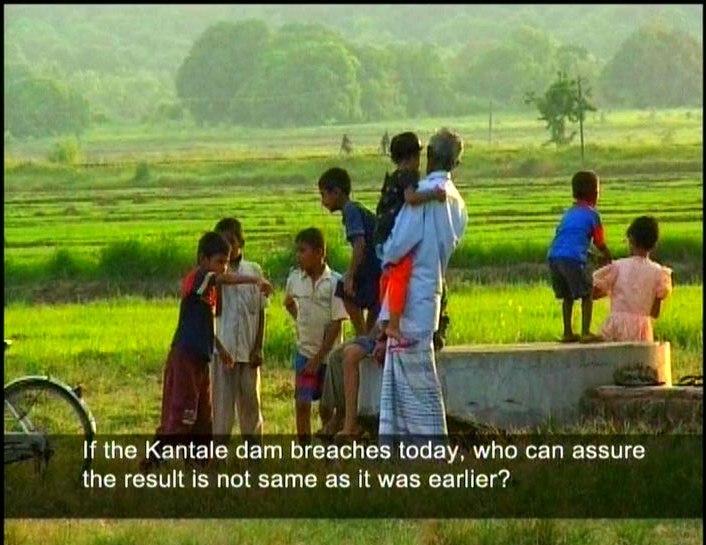

I’ve been asking such questions for a while. In fact, the post-mortem of the Kantale dam breach was one of the bigger stories I covered soon after I entered mainstream journalism in late 1987. By then, a few months after the incident, a presidential commission of inquiry was looking into what caused that particular disaster.

My interest in this subject is perhaps inevitable. I live in a country that has a high concentration of man-made water bodies. There are approximately 320 large and medium sized dams in Sri Lanka, and over 10,000 smaller dams, referred to as “wewas”, most of them built more than 1,000 years ago. In fact, Sri Lanka probably has the highest number of man-made water bodies in the world. According to the Sri Lanka Wetlands Database, the major irrigation reservoirs (each more than 200 hectares) cover an area of 7,820 hectares, while the seasonal/minor irrigation tanks (each less than 200 hectares) account for 52,250 hectares. This adds up to 60,070 hectares or just over 600 square kilometres — nearly a tenth of the island’s total land area.

Lankans are justifiably proud of their ancient hydrological civilisation — but don’t take enough care of it. Nothing lasts forever, of course, but irrigation systems can serve for longer if properly maintained. In a world where extreme weather is becoming increasingly commonplace, we can’t afford to sit on 25 centuries of historical laurels. Unless we maintain the numerous dams and irrigation systems – most of which are still being used for farming – heritage can easily turn into hazard.

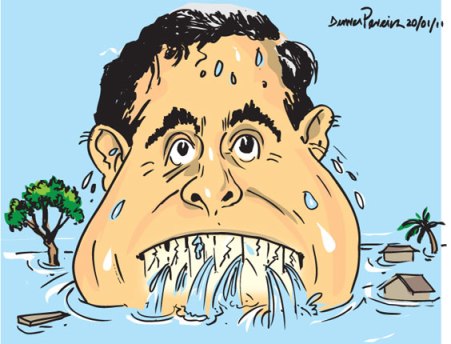

More than 200 small dams did breach during those rains, causing extensive damage to crops and infrastructure. The most dangerous form of breach, the over-topping of the earthen dams of large reservoirs, was avoided only by timely measures taken by irrigation engineers — at considerable cost to those living downstream. This irrigation emergency was captured by a local cartoonist: the head in this caricature is that of the minister of irrigation.

In early February, Sri Lanka announced that it will expand its dam safety programme to cover more large reservoirs and will ask for additional funding from the World Bank following recent floods. Never mind the irony of a proud heritage now having to be maintained with internationally borrowed money. Public safety, not national vanity, comes first.

All this provided a timely setting for the 2nd LIRNEasia Disaster Risk Reduction Lecture in Colombo, which I chaired and moderated. This enabled the issues of flood protection and dam safety to be revisited, building on the path-finding work in 2005-2006 done by LIRNEasia, Vanguard Foundation and Sarvodaya in developing an early warning system for dam hazards in Sri Lanka.

Dams and irrigation systems are widely seen as the exclusive domain of civil engineers. They certainly have a critical role to play, but are not the only stakeholders. I was very glad that both our panel and audience included voices from many of these groups — especially the many communities who live immediately downstream of dams and reservoirs. Some of them are always in the shadow of a dam hazard, and yet helpless about it.

This was the gist of farmer leader Bandula Mahanama’s remarks – he made a passionate plea for a more concerted effort to improve proper maintenance of dams and reservoirs. “Wewas are part of our life, but right now our lives are in danger because the irrigation heritage is in a state of disrepair,” he noted.

I will write more about this in the coming weeks. My last thought from the chair was something I first heard many years ago in a global documentary. When it comes to water management, everybody lives downstream.

That’s certainly the case — but some are more downstream than others. And not everyone lives with the same peace of mind. We need to do something about it.

See also my recent writing in Sinhala on this topic, as part of my weekly science and development column in the Ravaya newspaper in Sri Lanka:

Nalaka Gunawardene’s Ravaya column – 27 Feb 2011 – Dam Safety in Sri Lanka