Why can’t we humanitarian workers talk to each other in the field?

Why must we, instead, badger and harass people affected by a disaster or war, asking them for the same information over and over again?

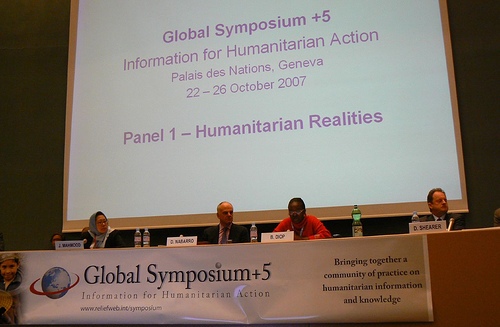

With these simple yet important questions, Dr Jemilah Mahmood, President of MERCY Malaysia, started off the first panel discussion on humanitarian realities at the Global Symposium+5 on ‘Information for Humanitarian Action’ organised by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN-OCHA). The meeting, held in Geneva from 22 – 26 October 2007 at the Palais des Nations, has brought together over 200 persons involved or interested in information and communication aspects of humanitarian work.

I was nearly dozing off on a surfeit of humanitarian jargon and acronyms when Jemilah started her reality check. The medical doctor turned humanitarian leader spoke from her heart, and spoke such common sense that sometimes seemed to elude the self-important UN types.

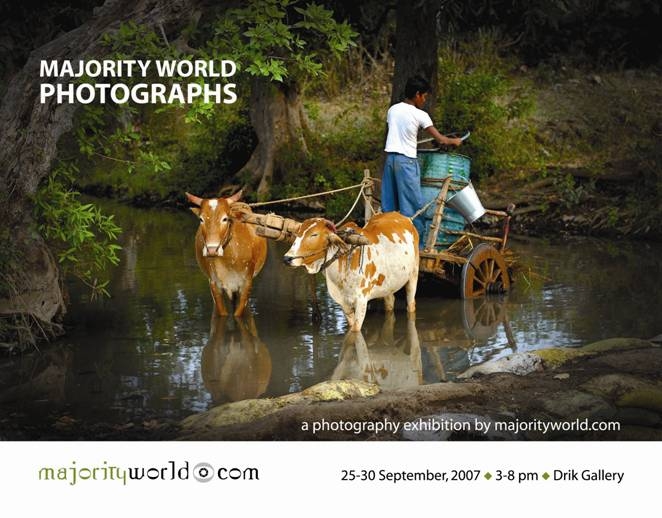

Jemilah argued that there was a greater need for community based information gathering and communication, rather than just data mining that often takes place in crisis or emergency situations.

“Communication with affected communities needs to be a genuinely two-way process,” she said, echoing the discussions at my own working group on ‘Communicating with affected communities in crisis’.

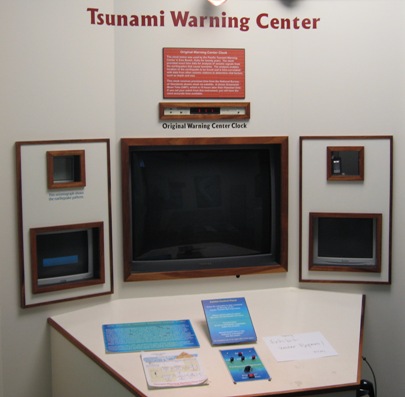

She talked of people in Aceh, Indonesia, and elsewhere who survived the tsunami — and then faced a barrage of questions and questionnaires from an endless stream of aid workers, many of who asked the same questions again and again! Why couldn’t the first group/s who surveyed survivors not have shared the information they gathered, she wondered.

“I sometimes see how humanitarian agencies are fighting with each other to keep field information to themselves,” she revealed.

There is also a need for humanitarian workers to be more sensitive to and respectful of affected people’s culture and social norms. For example, it is inappropriate to go to predominantly muslim communities and ask about their sexual habits or probe incidents of rape — even though gathering such information would be relevant in some situations. “The humanitarian workers need to find the right ways to tackle these and other challenges,” she said.

Sometimes well meaning aid workers inadvertently overstep their boundaries. In the aftermath of the Pakistan earthquake of October 2005, community meetings were scheduled at times when the people had to break their day-time fasting.

Today’s crisis affected people are becoming better informed and more empowered. Jemilah recalled how mobile phones are increasingly spreading news and information among crisis affected people on the arrival of new food or medicinal stocks. Once in Aceh, the news of vaccine stock arrival spread within hours through mobile texting or SMS, prompting thousands of people to turn up asking for this service.

The humanitarian community needs to combine technology, common sense and human considerations to deliver better services and benefits, she argued. “Technology alone won’t do this for us, but it offers us useful tools,” she said.

She added: “There are huge opportunities to use modern communication technologies to plan better, reduce disaster risks and have a well coordinated response in times of disasters.”

In short, we need locally relevant, low-cost solutions to improve information gathering, information sharing and communication all around, she argued.

MERCY Malaysia is an internationally recognised medical and humanitarian relief organisation. “MERCY Malaysia is not just a response organisation,” says its president Dr Jemilah Mahmood. This realisation came during the Afghanistan crisis (in October, 2001), when members decided it would be more prudent to look towards providing Total Disaster Risk Management (TDRM) to ensure that affected communities become more resilient after a disaster.

Since its inception, MERCY Malaysia has served hundreds of thousands of victims of natural and complex humanitarian disasters from Kosova, Indonesia, India, Turkey, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Iraq, Iran and Sudan. Hundreds of volunteers, both from the medical and non-medical field, have been trained and deployed to these areas. Dr. Jemilah Mahmood herself has led most of these missions at home and abroad, in particular to Kosova, Indonesia, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Iraq and most recently to Palestine.

Read The Star newspaper (Malaysia) article on MERCY Malaysia on 12 October 2007

All Geneva photos courtesy UN-OCHA Flickr on Global Symposium+5