What is the world’s worst peace-time maritime disaster?

No, it’s not the sinking of the Titanic. It’s a disaster that happened 75 later, on the other side of the planet – in Asia.

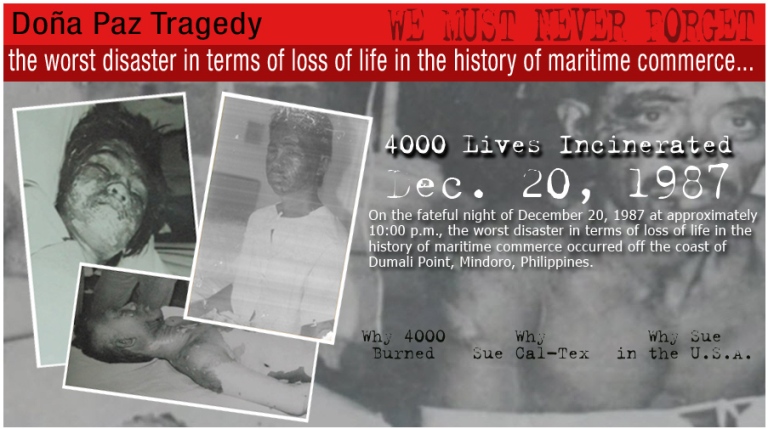

It is the sinking of the MV Doña Paz, off the coast of Dumali Point, Mindoro, in the Philippines on 20 December 1987. That night, the 2,215-ton passenger ferry sailed into infamy with a loss of over 4,000 lives – many of them burnt alive in an inferno at sea.

Nobody is certain exactly how many lives were lost — because many of them were not supposed to be on that overcrowded passenger ferry, sailing in clear tropical weather on an overnight journey.

Passenger ferries like the Doña Paz are widely used in the Philippines, an archipelago in Southeast Asia comprising over 7,000 islands. They are among the cheapest and most popular ways to travel.

Just 5 days before Christmas of 1987, hundreds of ordinary people boarded the Doña Paz for a 24-hour voyage from the Leyte island to Manila, the capital.

The Doña Paz – originally built and used in Japan in 1963 and bought by a Filipino ferry company in 1975 — was authorized to carry a maximum load of 1,518 passengers.

But the on the night of the accident, survivors say there may have been more than 4,000 people on board – a gross violation of safety procedures.

Only 24 of them survived the journey — and only just. The entire crew and most of its passengers perished in an accident happened due to negligence, recklessness and callous disregard for safety.

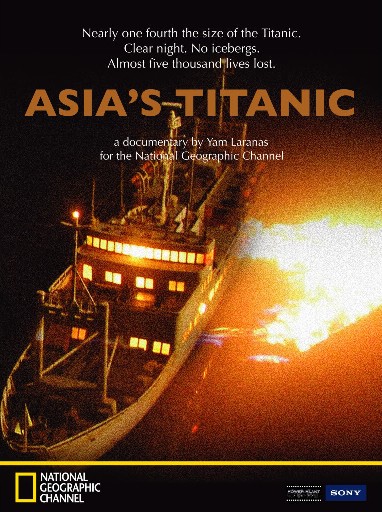

For a glimpse of what happened, watch these first few minutes from 2009 National Geographic documentary,Asia’s Titanic:

For a summary compiled from several journalistic and activist sources, read on…

The Doña Paz had an official passenger list of 1,493 with a crew of 59 on board. But later media investigations showed that the list did not include as many as 1,000 children below the age of four — and many passengers who paid their fare after boarding.

The ship was going at a steady pace. The passengers were settling in for the night. The Doña Paz was scheduled to arrive in Manila by morning. A survivor later said that the weather that night was clear, but the sea was choppy.

Around 10.30 pm local time, without any warning, the Doña Paz collided with another vessel. It was no ordinary ship: the MT Vector was en route from Bataan to Masbate, carrying 8,800 barrels of gasoline, diesel and kerosene owned by Caltex Philippines.

Immediately upon collision, the tanker’s cargo ignited, setting off a massive fire that soon engulfed both ships. Thousands of passengers were trapped inside the burning ferry.

Dozens of passengers leaped into the sea without realizing that the petroleum products had also set the surrounding seas ablaze. Those in the water had to keep diving to avoid the flames spreading on the surface.

Of all the passengers and crew on board, only 24 survived. Everything known about this maritime disaster is based largely on their accounts – and investigative work done by a handful of journalists.

One survivor claimed that the lights onboard went out soon after the collision: there had been no life vests on the Doña Paz, and that none of the crew was giving any orders. It was later said that the life jackets were locked up beyond emergency reach.

The few survivors were later rescued swimming among many charred bodies in the shark-infested Tablas Strait that separates Mindoro and Panay islands.

The first help arrived at the scene around one and a half hours after the collision – it was another passing ship. By this time, most passengers of the ferry were dead.

The Doña Paz sank within two hours of the collision, while the Vector sank in four hours. The sea is about 545 meters deep in the collision site.

The Philippines Coast Guard did not learn about the disaster until eight hours after it happened. An official search and rescue mission took more hours to get started.

In the days that followed, the full scale of the horrible tragedy became clear. The ferry’s owner company, Sulpicio Lines, argued that the ferry was not overcrowded. It also refused to acknowledge anyone other than those officially listed on its passenger manifest.

Manifests on Philippine inter-island vessels are notoriously inaccurate. They often record children as “half-passengers” or disregard them entirely. Corrupt officials frequently accept bribes to allow overloading.

Many victims were probably incinerated when the vessels exploded and will never be accounted for. Rescuers found only 108 bodies, many of them charred and mutilated beyond recognition. More bodies were later washed ashore to nearby islands where the local people buried them after religious rituals.

Many victims were probably incinerated when the vessels exploded and will never be accounted for. Rescuers found only 108 bodies, many of them charred and mutilated beyond recognition. More bodies were later washed ashore to nearby islands where the local people buried them after religious rituals.

All officers on board the Doña Paz were killed in the disaster, and the two from the Vector who survived had both been asleep at the time. This left the field entirely to lawyers from all sides to endlessly argue over what went wrong, how – and who was responsible.

It was later found that, at the time of the collision, both ships had been moving slowly: the Doña Paz at 26 km per hour, and Vector at 8 km per hour. They were surrounded by 37 square km of wide open sea – plenty of time and space to avoid crashing into each other!

Experts also wondered why the two ships had not communicated with each other before the crash. It is internationally required that all ships carry VHF radio. The Vector was found to have an expired radio license. The radio license for the Doña Paz was a fake.

Survivors told investigators that the crew of the Doña Paz were having a party on board minutes before it collided with the oil tanker. Some reports suggested that the captain himself had been among the revelers.

Being ordinary people, the passenger didn’t know details of maritime rank or procedure. It is likely that a mate or apprentice was steering the Doña Paz. Not a single crew member survived to tell their version of the incident.

After a long and contentious inquiry, the investigators placed the blame on the Vector.

Independent analyses have identified multiple factors that contributed to this tragedy: lack of law enforcement arising from corruption and connivance; under-qualified and overworked crew; telecommunications failures; and inadequate search and rescue efforts in the event of accidents.

Directed by award-winning Filipino director Yam Laranas, it was the first for any Filipino filmmaker to direct a full-length documentary for the global channel noted for its factual films.

Through dramatic first hand accounts from survivors and rescuers, transcripts from the Philippine congressional inquiry into the tragedy, archival footage and photos and a re-enactment of the collision, dissect the unfolding tragedy of Doña Paz.

The 10-million Filipino peso project took more than 3 years to make, but even its makers could not find all the answers.

“The truth may never be known. In the years after the Doña Paz tragedy, shipping disasters continue to plague the Philippines,” says the documentary as it ends.

Watch the NatGeo film in full on Doña Paz survivors’ website

Meanwhile, nearly 25 years on, the struggle for justice for the victims and survivors is still on.

Related post: Baby Ruth Villarama on researching and filming “Asia’s Titanic” for National Geographic