On 19 July 2007, I wrote about the need for natural history and environment film-makers to take their films back to the locations and communities where they filmed.

I cited the specific example of the Brock Initiative, started by ex BBC Natural History producer Richard Brock, which is supporting projects in several countries in Africa and Asia.

In today’s mail, I received the DVD of Tiger – the death chronicles, the latest documentary by the award-winning Indian film-maker Krishnendu Bose. I’m going to watch and write about it separately, but this reminded me of the outreach work he and his company, Earthcare Films, have been doing for years.

After working for a dozen years with factual film-makers from across Asia, my experience is that not many are really interested in any outreach besides a high profile broadcast. For sure, broadcasts help draw attention to a film and its creator/s. But as we have discussed in recent blog posts, broadcast television is not an ideal platform to get a discussion going on issues and concerns. In fact, many film makers are finding it harder to get their serious films broadcast at times with better audience ratings.

Still, surprisingly few film-makers have time or patience for serious narrowcast outreach. Yes, it is a time consuming, tedious process. The logistics can be demanding and expensive. And there is not much glamour (or ‘arty and intellectual feel’) in going to a small town or remote village and playing back your film to a few dozen people living on the edge of survival.

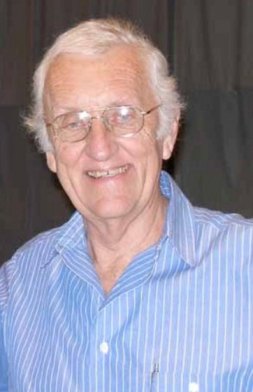

But as exceptional film-makers like Krishnendu (in photo above, taken from Earthcare Films website) know well, it can be an enormously enriching and satisfying experience for a film-maker. People like him watch the audience while they watch the film.

“Films are a greatly underused communication form. Serious communication usually is at most limited to awareness building,” says Earthcare Films website in its section on outreach.

That’s why EarthCare Outreach wants to explore beyond. “Films could be tools for social change and empowerment. Participatory film-making by sharing skills and capacities could take the ‘use’ of films to a different level. Not that it has not been tried and practised, but we want to take it forward and try and push the boundaries.”

Krishnendu and colleagues have set up the EarthCare Outreach Trust specifically for this purpose. The objective is “to create ownership and stake in the process and the product of a documentary film of the people whose lives we document. In the process we strive to empower young people and rural communities to make them stakeholders in decision-making and in planning for natural resource management.”

For the past several years, Earthcare Outreach has been active on these fronts, organising mobile film screenings or traveling film festivals in rural and urban areas in different parts of India. The website talks about how they have held community and citizenry exchanges between selected locations, evolving film-making skill-share across these groups.

Read more about Earthcare Outreach activities.

Contact Earthcare Films for more information and involvement

On a personal note, I’m trying to recall when I first met Krishnendu. It must be at least a decade ago — I had seen some of his work before I met the man behind them. We were together as guests of the Earth Vision Tokyo Global Environmental Film Festival in 2001 — where his film, Harvesting Hunger, (image below shows it being filmed) won a special jury award.