This is Jureerat Pechsai, nicknamed Deun.

She is a member of the Moken community – indigenous people living on the coast and islands on Thailand’s southern coast. Their nomadic lifestyle has earned them the name Sea Gypsies. In Thai, they are called Chao Ley — or people of the sea.

They traditionally live on small boats and move from place to place. When the Monsoon rains make the seas rough, they set up temporary huts on islands – such as Pra Thong Island, where Deun lives.

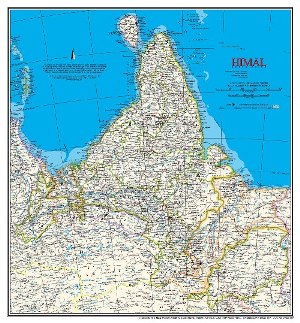

Pra Thong is an hour’s boat ride from the mainland city of Phuket — some conservationists call it one of the “Jewels of the Andaman” for its biodiversity. It is also an important nesting beach for turtles.

It was on this island that my colleagues from TVE Asia Pacific met and filmed with her in late 2006 for our Asian TV series, The Greenbelt Reports.

The Asian Tsunami of December 2004 devastated the Moken way of life. Their temporary huts were destroyed, and many families lost loved ones. The losses would have been greater if not for the mangrove forest close to the Moken village.

“Moken loves the water, the forest and everything. And we love the mangrove forest the most. The mangrove forest is like a living creature that has helped the Moken people for years. It’s our most beloved place on the island,” says Khiab Pansuwan, an older woman who is a leader in Deun’s community.

After the Tsunami, some Moken felt that they could not return to their nomadic lives. They have chosen to live on the mainland where they feel safe from the waves. Others who remained on their island had new, permanent houses built for them. But the Moken are quick to abandon these whenever they hear rumours of more Tsunamis.

Watch The Greenbelt Reports: Love Thy Mangrove on YouTube:

The mangrove replanting work on Pra Thong island is led by two women, Khiab and Deun.

Deun has been a volunteer with conservation organisations. She learnt about ecosystems and how to protect mangroves and endangered species like sea turtles. She can see many changes in her environment after the tsunami.

“After the tsunami, there are a lot of changes. We didn’t have much grass before, but now weeds are everywhere. The weeds are now more than grass,” says Deun. “In the past, we used to have more and more beach every year. But now the sea has come so close…”

The Tsunami’s impact is not the only factor affecting the mangroves here. Dynamite fishing, oil from boats, foam from fish and oyster nets are all damaging this life-saving greenbelt. Some people also cut down mangrove trees.

But Khiab and Deun are determined to rally everyone around to replant and regenerate their mangroves.

Says Khiab: “The community forest is part of the Moken people. We don’t want to cut the trees or clear it. We want to replant the trees so the forest is like before. We don’t want anyone to cut down trees because the mangrove forest saved many Moken lives.”

The two women are determined to rally everyone around to replant and regenerate their mangroves.

Replanted mangroves will ensure not only protection from the waves, but also a continued supply of shell fish and crabs – the main source of income and food for the Moken.

The Moken have traditionally managed the mangroves sustainably. They fish in different areas of the forest during the year, giving time for fish stocks to regenerate. Logging for firewood is done only in moderation, in designated areas.

But these mangroves are now under threat from outsiders who see it as a source of firewood and shell fish. Only a few Moken are left in the village to protect the forest from these intrusions.

Khiab and Deun have much work to do.

NOTE: We are now looking for more stories like this to be featured in the second Asian TV series of The Greenbelt Reports. See TVEAP website news story calling for story ideas.

All images and video courtesy TVE Asia Pacific