Some of us dream about doing great things. Other agitate for reform. A few among us just go ahead and do it.

This story is about one such group, and its inspirational leader, who took on the formidable challenge of setting up an educational television channel for South Asia.

Just thinking about it can scare away most people. Home to over 1.5 billion people, including the largest concentration of poor anywhere in the world, South Asia is in a region full of disparities, divisions and desperation. It is not only the most militarised region in the world, but also one of the most highly bureaucratised (the British invented bureaucracy and we in South Asia perfected it!). Starting a new venture of any kind is fraught with endless permissions and paperwork.

None of this deterred Rashid Latif from launching Ujala TV in mid 2006 as a free, 24-hour satellite television channel dedicated to education and information with focus on South Asia.

Ujala TV is wholly owned and operated by a non-profit entity called the People’s Education Network (PEN) that Rashid founded.

As the channel’s website says: ”A refreshing new television alternative, Ujala does not belong to any nation – it belongs to South Asia. Showcasing both local and international programs our goal is to help ease the barriers placed between us and within our own minds.”

Ujala TV’s test transmissions started on 2 July 2006 from Dubai, where Latif assembled his small team of hard-working professionals at the Dubai Media City. This was a smart move: not to be anchored in any single country in South Asia itself when broadcasting to the region.

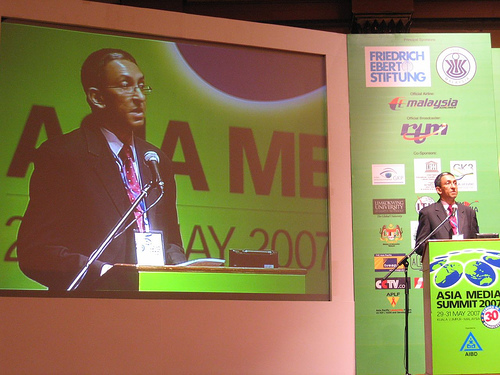

Photo shows (L to R) Rashid Latif, Nalaka Gunawardene and Sohail Khan in Dubai, May 2006

As Sohail Khan, Director Operations of Ujala TV, recalled recently: “I still cherish the excitement when I was at Samacom (the Uplink Earth Station at Dubai) at around 2 am Dubai Time to press the button to air Ujala for the very first time at 00:00 GMT on 2 July 2007 (4 am Dubai Time) to start the Test Transmission.”

They had worked long and hard to get to that point. A few weeks earlier, in mid May 2006, I stopped over in Dubai specifically to meet Rashid and his team who were busy preparing to launch. At that time, they were working out of their office for 16 – 18 hours a day, every day, and sleeping a few hours at the office itself.

This was no multi-million dollar start up channel. The entire operation was being financed by Rashid Latif from personal funds. Although the channel’s aims were entirely in the public interest, he declined to seek funding from development donors or philanthropic foundations.

A Pakistan-born Canadian citizen, Rashid worked in the Pakistan government as a senior broadcast manager before heading west to work in the corporate sector. He started Ujala TV after formal retirement.

“I started working on ‘Ujala’ project (at the age of 75) when most of my contemporaries had either played their innings or were about to pack up and leave for the pavilion,” Rashid said in a recent letter.

Until this letter, I had no idea that Rashid was 75. He has the energy and drive of someone in his late 50s or early 60s!

Sohail looks back on the first year: “During this first year, we came across many difficulties, including, changing laws in India and Pakistan for Landing Rights with huge financial requirements, and increase in running costs due to change in different rentals here in Dubai. These problems, however, do not have any effect on our determination, and we are still trying to eliminate the darkness from our part of the world, and to spread Ujala.”

The new channel still struggles to establish its brand identity and distribution networks — it’s not easy to compete with big corporations with their deep pockets.

But a modest start has been made. Now we need to sustain the momentum.

Meanwhile, Rashid is looking for a dynamic South Asian national to take over from him, so that he can fully retire. Now that’s going to be a tall order.

Declaration of interests:

1. I am on the honorary Board of Governors of People’s Education Network along with over a dozen academics, journalists and film-makers who share Rashid’s ideal for a South Asian public interest TV channel.

2. TVE Asia Pacific has supplied many development films to Ujala TV over the past few months.

Read Aman Malik’s article in Himal Southasian on Channel Southasia