There I was, coming out of a Dhaka gutter, badly shaken and splattered with the mega-city’s assorted muck.

A minute earlier, I had stepped right into it in the semi-darkness of the evening. I had no idea it was coming. One moment I was walked on the side of a busy but not-too-well-lit street in the Bangladeshi capital. The next, I was thigh-deep inside an open drain carrying municipal waste and drain water.

In the fading light, the blackness of the tarred road and the gutter water merged seamlessly, creating an illusion of solid surface.

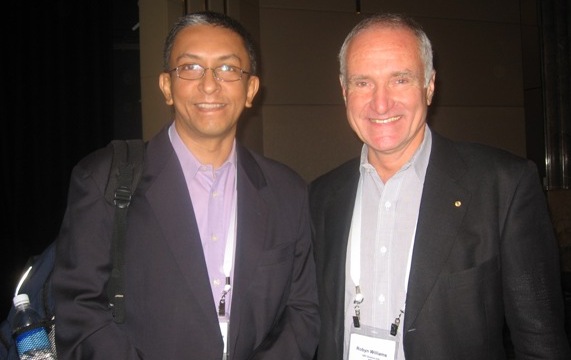

My friend Shahidul Alam (below, right, with me in a happier moment), who was a few feet away, moved fast and pulled me out. As I felt my legs and feet, I realised how lucky I had been: in spite of falling two feet deep, I was unhurt – no cuts and bruises, not even a scrape (thank goodness I was wearing shoes).

Shahidul was taking me out for dinner, and then to the airport, but Dhaka’s evening traffic had wrecked our plans. We were caught in an enormous jam caused by Bashundhara City, the US Dollar 100 million shopping mall said to be South Asia’s largest (and 12th largest in the world). There was some incongruity in that, but we were keen to get to a restaurant where we had a rendezvous with some other friends.

In the event, we were too delayed and I was risking missing my flight. So Shahidul, the excellent host that he always is, decided to buy me some take-away food that I could eat on the way to the airport. He parked his car near a wayside eatery, and called me out to choose what I’d like.

I was walking a few steps behind him when I fell into the open, concealed gutter.

If I had to fall right down to Earth, I couldn’t have chosen a better date: it was Earth Day, 22 April 2006.

After I was pulled out of the gutter, we had to move quickly. I was three hours away from my flight to Singapore, and there was no way any airline would carry someone in my condition. I had already checked out of my Dhaka hotel, and in any case that was almost two hours behind us in another part of the city.

Shahidul approached the staff in a nearby restaurant – a very ordinary one – and explained what had happened. The Bengali hospitality and kindness snapped into action. I was given immediate access to their modest wash room, where I washed and changed into clothes pulled out of my travel bag.

I had to reluctantly dump my well-used pair of shoes. Shahidul lent me his sandals, and found a taxi to rush me to the airport while he’d team up with the others to join the belated dinner.

I made it to the airport – and the flight – in good time. And as far as I could tell, no one gave me strange looks as I winged my way to Singapore. After all that excitement, I even managed to get some sleep on the flight.

But I had no illusions about what happened. For one thing, I’d escaped with no injury of any kind. For another, I had merely glimpsed and only very slightly experienced a daily reality for millions of city dwellers across developing Asia.

I should know. I live in suburban Colombo, the Sri Lankan capital, which has its own problems of waste disposal and cleanliness. The only difference is that in mega-cities like Dhaka (estimated population close to 12 million), the issues are multiplied and magnified.

We who live in middle class ‘oases’ within these cities tip-toe around the worst realities that the poorer citizens grapple with on a daily basis. They lack the choices that we have.

As a development journalist, I’ve written about urban sprawl, mega-cities and environmental challenges in developing Asia, where more people are now living in cities than ever before in history. UN Habitat says half of humanity has now become city dwellers. With their misleading image as centres of vast opportunity and prosperity, cities are a magnet to millions of rural poor. Like Dick Wittington, who thought the streets of London were paved with gold, they migrate to towns and cities in search of better lives. Most end up swelling the already burgeoning cities, exchanging their rural poverty for urban squalor.

Falling thigh-deep into a Dhaka gutter for a minute or two is no big deal when compared to the unsafe, unclean environments that they live in, every day and every night.

And they can’t just walk into a wayside restaurant, wash away the muck, and catch the next flight to clean, safe and landscaped Singapore.

Read my December 2006 essay, Grappling with Asia’s Tsunami of the Air

Photograph by Dhara Gunawardene