Text of my column written for Echelon monthly business magazine, Sri Lanka, July 2015 issue

Kidney Disease Needs ‘Heart and Mind’ solutions

By Nalaka Gunawardene

If bans and prohibitions were a measure of good governance, Sri Lanka would probably score well in global rankings. Successive governments have shown a penchant for banning – usually without much evidence or debate.

The latest such ban concerns glyphosate — the world’s most widely used herbicide – on the basis that it was causing chronic kidney disease in parts of the Dry Zone.

First, President Maithripala Sirisena announced such a ban in late May (which earned him lots of favourable coverage in environmental and health related websites worldwide).

Then, on 29 May 2015, state-owned Daily News reported under Cabinet decisions: “The scientists who carry out research on renal diseases prevailing in many parts of the country have pointed out that the use of pesticides, weedicides and chemical fertiliser could be contributing to this situation. Accordingly the government has already banned the import and usage of four identified chemical fertilizer and pesticides. In addition to this President has decided to totally ban the import and usage of glyphosate.”

Finally, the Finance Ministry on 11 June gazetted regulations banning the import of glyphosate under the Import and Export (Control) Act. By mid June, it was still unclear whether the ban is comprehensive, or an exception is to be made for tea plantations that rely heavily on this weedicide in lieu of costly labour for manual weeding.

Has this decision tackled the massive public health and humanitarian crisis caused by mass kidney failure? Sadly, no. The new government has ignored the views of a vast majority of Lankan scientists, and sided with an unproven hypothesis. This undermines evidence-based policy making and allows activist rhetoric to decide affairs of the state.

A Silent Emergency

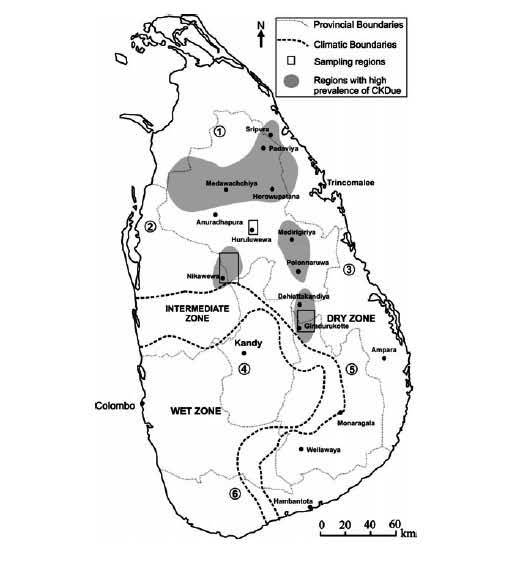

The chronic kidney disease was first reported from certain parts of the Dry Zone in the early 1990s. Hundreds were diagnosed with kidney failure – but none had the common risk factors of diabetes, high blood pressure or obesity. Hence the official name: Chronic Kidney Disease of uncertain aetiology, or CKDu.

The disease built up stealthily in the body, manifesting only in advanced stages. By then, regular dialysis or transplants were the only treatment options. Most affected were male farmers in working age, between 30 and 60 years.

In early 2013, the Ministry of Health estimated that some 450,000 persons were affected. The cumulative death toll has been reported between 20,000 and 22,000, but these numbers are not verified.

The kidney specialist who first detected the disease worries that some activists are exaggerating CKDu numbers. Dr Tilak Abeysekera, who heads the department of nephrology and transplantation at the Kandy Teaching Hospital, underlines the critical need for correct diagnosis. CKDu should not be confused with regular types of kidney disease, he says.

In December 2013, he told a national symposium organised by the National Academy of Sciences of Sri Lanka (NASSL) that only 16% of kidney patients in the Anuradhapura district – ‘ground zero’ of the mystery disease – could be classified as having CKDu.

It is clear, however, that CKDu has become a national humanitarian emergency. Providing medication and dialysis for those living with CKDu already costs more than 5% of the country’s annual health budget. With each dialysis session costing around LKR 12,000 (and 3 or 4 needed every week), very few among the affected can afford private healthcare.

Besides the mounting humanitarian cost, CKDu also has implications for agricultural productivity and rural economies as more farmers are stricken. With the cause as yet unknown (although confirmed as non-communicable), fears, myths and stigma are also spreading.

Looking for Causes

For two decades, researchers in Sri Lanka and their overseas collaborators have been investigating various environmental, geochemical and lifestyle-related factors. They have come up with a dozen hypotheses, none of it proven as yet.

Among the environmental factors suspected are: naturally high levels of Fluoride in groundwater; use of Aluminium utensils with such water; naturally occurring hard water (with high mineral content); cyanobacterial toxins in water; pesticide residues; and higher than safe levels of Cadmium or Arsenic. Lifestyle factors studied include the locally brewed liquor (kasippu), and certain Ayurvedic medicinal concoctions. Genetic predisposition to kidney failure has also been probed in some areas.

Researchers are baffled why CKDu is found only in certain areas of the Dry Zone when these environmental and lifestyle factors are common to a much larger segment of population. This makes it much harder to pinpoint a specific cause.

The most comprehensive study to date, the National CKDu Research Project (2009-2011), concluded that CKDu results from not one but several causes. The multidisciplinary study, led by Ministry of Health with support from the World Health Organisation (WHO), highlighted several risk factors. These include long-term exposure to low levels of cadmium and arsenic through the food chain, which are linked to the wide use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides. Selenium deficiency in the diet and genetic susceptibility might also play a part, the study found.

These findings were academically published in BMC Nephrology journal in August 2013 (See: www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2369/14/180). The paper ended with these words: “Steps are being taken to strengthen the water supply scheme in the endemic area as well as the regulations related to procurement and distribution of fertilizers and pesticides. Further studies are ongoing to investigate the contributory role of infections in the pathogenesis of CKDu.”

Hazards of Pseudoscience

One thing is clear. Remedial or precautionary measures cannot be delayed until a full understanding of the disease emerges. Indeed, WHO has recommended taking care of the affected while science takes its own course.

Dr Shanthi Mendis, WHO’s director for managing non-communicable diseases, says: “CKDu is a major public health issue placing a heavy burden on government health expenditure and is a cause of catastrophic expenditure for families, leading to poverty and stigma in the community.”

CKDu needs a well-coordinated response from public health, agriculture and water supply sectors that typically fall under separate government ministries and agencies. We need to see mass kidney failure as more than just a public health emergency or environmental crisis. It is a sign of cascading policy failures in land care, water management and farming over decades.

In such complex situations, looking for a single ‘villain’ is both simplistic and misleading. For sure, the double-edged legacy of the Green Revolution — which promoted high external inputs in agriculture — must be critiqued, and past policy blunders need correction. Yet knee-jerk reactions or patchy regulation can do more harm than good.

“In Sri Lanka we have a powerful lobby of pseudoscientists who seek cheap popularity by claiming to work against the multinational corporations for their own vested political interests,” says Dr Oliver A Ileperuma, a senior professor of chemistry at Peradeniya University. In his view, the recent glyphosate ban is a pure political decision without any scientific basis.

His concerns are shared by several hundred eminent Lankan scientists who are fellows of NASSL, an independent scientific body (not a state agency). The Academy said in a statement in mid June that it was “not aware of any scientific evidence from studies in Sri Lanka or abroad showing that CKDu is caused by glyphosate.”

NASSL President Prof Vijaya Kumar said: “The very limited information available on glyphosate in Sri Lanka does not show that levels of glyphosate in drinking water in CKDu affected areas (North Central Province) are above the international standards set for safety. CKDu is rarely reported among farmers in neighbouring areas such as Ampara, Puttlam and Jaffna or even the wet zone, where glyphosate is used to similar extent. It has also not been reported in tea growing areas where glyphosate is far more intensively used.”

Agrochemical regulation

In recent years, the search for CKDu causes has become too mixed up with the separate case for tighter regulation of agrochemicals, a policy need on its own merit. International experience shows that a sectoral approach works better than a chemical by chemical one.

The bottomline: improving Sri Lanka’s agrochemical regulation needs an evidence-based, rigorous process that does not jeopardize the country’s food security or farmers’ livelihoods. A gradual shift to organic farming (currently practiced on less than 2% of our farmland) is ideal, but can take decades to accomplish.

Our health and environmental activists must rise above their demonise-and-ban approaches to grasp the bigger picture. They can do better than ridiculing senior scientists who don’t support populist notions. Effective policy advocacy in today’s world requires problem solving and collaboration – not conspiracy theories or confrontation.

Hijacking a human tragedy like CKDu for scoring cheap debating points is not worthy of any true activist or politician.

Proceedings of Dec 2013 NAASL National Symposium on CKDu are at: http://nas-srilanka.org/?page_id=1145

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene is on Twitter @NalakaG and blogs at http://nalakagunawardene.com