Feature article published in Ceylon Today broadsheet newspaper on 3 February 2013

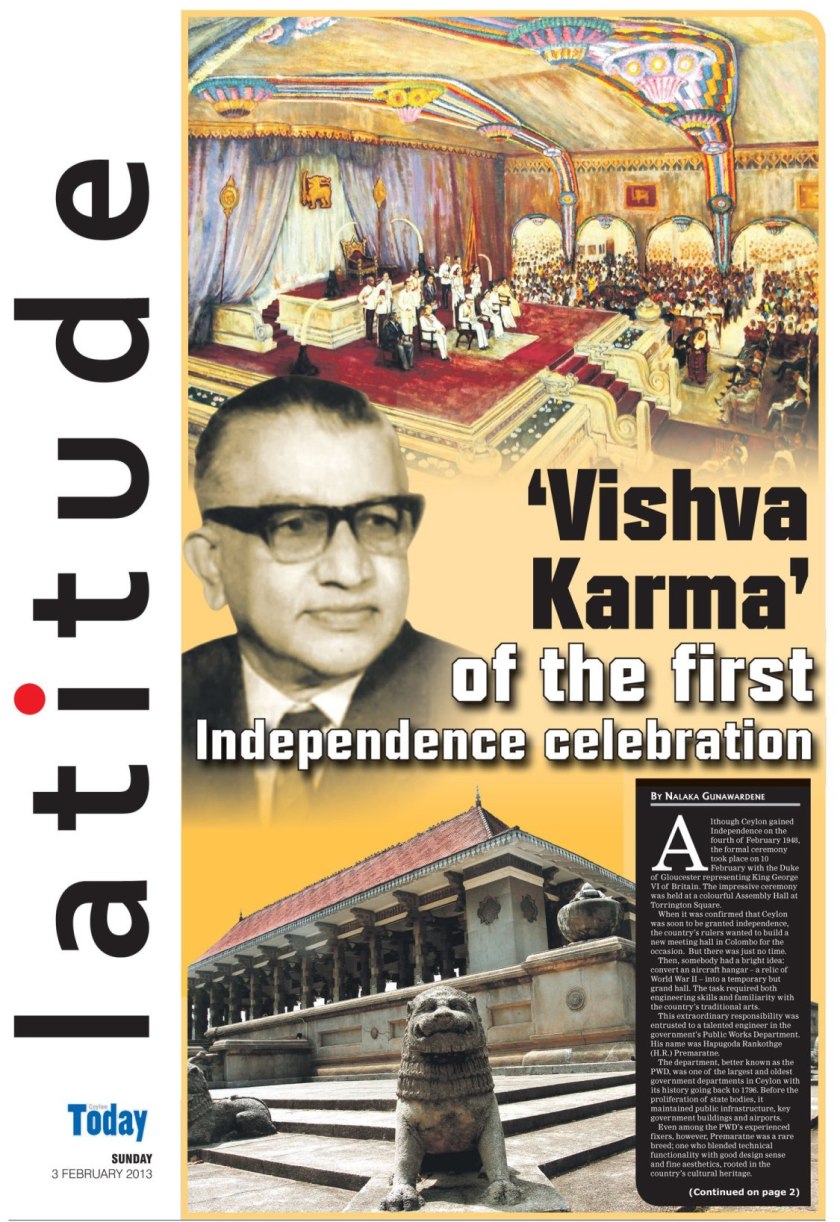

Although Ceylon gained Independence on 4 February 1948, the formal ceremony took place on February 10 with the Duke of Gloucester representing King George VI of Britain. The impressive ceremony was held at a colourful Assembly Hall at Torrington Square in Colombo.

When it was confirmed that Ceylon was soon to be granted independence, the country’s rulers wanted to build a new meeting hall in Colombo for the occasion. But there was just no time.

Then somebody had a bright idea: convert an aircraft hanger – a relic of World War II — into a temporary but grand hall. The task required both engineering skills and familiarity with the country’s traditional arts.

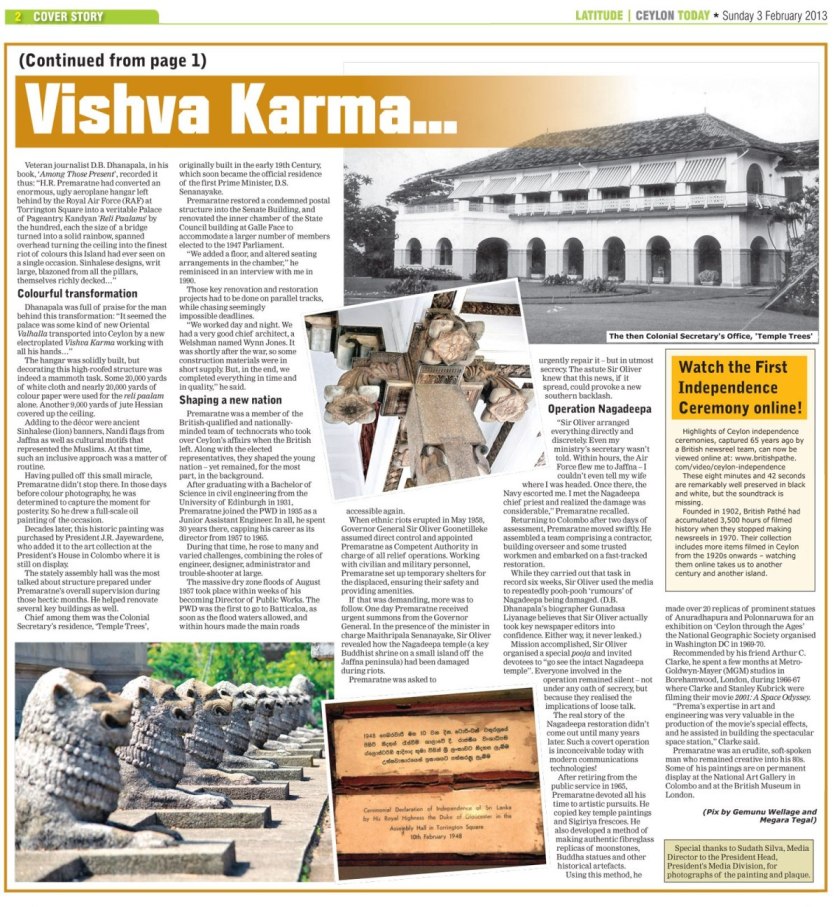

This extraordinary responsibility was entrusted to a talented engineer in the government’s Public Works Department. His name was Hapugoda Rankothge (H R) Premaratne.

The department, better known as the PWD, was one of the largest and oldest government departments in Ceylon with its history going back to 1796. Before the proliferation of state bodies, it maintained public infrastructure, key government buildings and airports.

Even among the PWD’s experienced fixers, however, Premaratne was a rare breed – one who blended technical functionality with good design sense and fine aesthetics rooted in the country’s cultural heritage.

Colourful transformation

Veteran journalist D B Dhanapala, in his book Among Those Present, recorded it thus: “H R Premaratne had converted an enormous, ugly aeroplane hanger left behind by the RAF at Torrington Square into a veritable Palace of Pageantry. Kandyan ‘Reli Paalams’ by the hundred, each the size of a bridge turned into a solid rainbow, spanned overhead turning the ceiling into the finest riot of colours this Island had ever seen on a single occasion. Sinhalese designs, writ large, blazoned from all the pillars, themselves richly decked…”

Dhanapala was full of praise for the man behind this transformation: “It seemed the palace was some kind of new Oriental Valhalla transported into Ceylon by a new electroplated Vishva Karma working with all his hands…”

The hanger was solidly built, but decorating this high-roofed structure was indeed a mammoth task. Some 20,000 yards of white cloth, and nearly 20,000 yards of colour paper were used for the ‘reli paalam’ alone. Another 9,000 yards of jute Hessian covered up the ceiling.

Adding to the décor were ancient Sinhalese (lion) banners, Nandi flags from Jaffna, as well as cultural motifs that represented the muslims. At that time, such an inclusive approach was a matter of routine.

Having pulled off this small miracle, Premaratne didn’t stop there. In those days before colour photography, he was determined to capture the moment for posterity. So he drew a full scale oil painting of the occasion.

Decades later, this historic painting was purchased by President J R Jayewardene who added it to the art collection at the President’s House in Colombo where it is still on display (main photo).

The stately assembly hall was the most talked about structure prepared under Premaratne’s overall supervision during those hectic months. He helped renovate several key buildings as well.

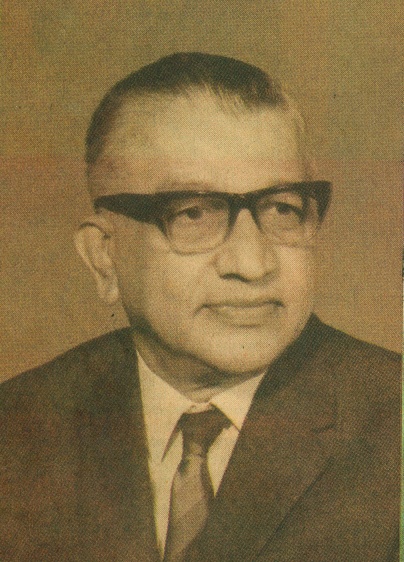

Chief among them was the Colonial Secretary’s residence ‘Temple Trees’, originally built in the early 19th century, which soon became the official residence of the first Prime Minister D S Senanayake.

Premaratne restored a condemned postal structure into the Senate Building, and renovated the inner chamber of the State Council building at Galle Face to accommodate a larger number of members elected to the 1947 Parliament.

“We added a floor, and altered seating arrangements in the chamber,” he reminisced in an interview with me in 1990.

Those key renovation and restoration projects had to be done on parallel tracks, while chasing seemingly impossible deadlines.

“We worked day and night. We had a very good chief architect, a Welshman named Wynn Jones. It was shortly after the War, so some construction materials were in short supply. But in the end, we completed everything in time and in quality,” he said.

Shaping New Nation

Premaratne was a member of the British qualified and nationally minded team of technocrats who took over Ceylon’s affairs when the British left. Along with the elected representatives, they shaped the young nation — yet remained, for the most part, in the background.

After graduating with a BSc in civil engineering from the University of Edinburgh in 1931, Premaratne joined the PWD in 1935 as a Junior Assistant Engineer. In all, he spent 30 years there, capping his career as its director from 1957 to 1965.

During that time, he rose to many and varied challenges, combining the roles of engineer, designer, administrator and trouble-shooter at large.

The massive Dry Zone floods of August 1957 took place within weeks of his becoming Director of Public Works. PWD was the first to go to Batticaloa, as soon as the flood waters allowed, and within hours made the main roads accessible again.

When ethnic riots erupted in May 1958, Governor General Sir Oliver Goonetilleke assumed direct control appointed Premaratne as Competent Authority in charge of all relief operations. Working with civilian and military personnel, Premaratne set up temporary shelters for the displaced, ensuring their safety and providing amenities.

If that was demanding, more was to follow. One day Premaratne received urgent summons from the Governor General. In the presence of the minister in charge Maithripala Senanayake, Sir Oliver revealed how the Nagadeepa temple (a key Buddhist shrine on a small island off the Jaffna peninsula) had been damaged during riots.

Premaratne was asked to urgently repair it – but in utmost secrecy. The astute Sir Oliver knew that this news, if it spread, could provoke a new southern backlash.

Operation Nagadeepa

“Sir Oliver arranged everything directly and discretely. Even my ministry’s secretary wasn’t told. Within hours, the Air Force flew me to Jaffna — I couldn’t tell even my wife where I was headed. Once there, the Navy escorted me. I met the Nagadeepa chief priest, and realised the damage was considerable,” Premaratne recalled.

Returning to Colombo after two days of assessment, Premaratne moved swiftly. He assembled a team comprising a contractor, building overseer and some trusted workmen and embarked on a fast-tracked restoration.

While they carried out that task in record six weeks, Sir Oliver used the media to repeatedly pooh-pooh ‘rumours’ of Nagadeepa being damaged. (D B Dhanapala’s biographer Gunadasa Liyanage believes that Sir Oliver actually took key newspaper editors into confidence. Either way, it never leaked.)

Mission accomplished, Sir Oliver organised a special pooja and invited devotees to ‘go see the intact Nagadeepa temple’. Everyone involved in the operation remained silent – not under any oath of secrecy, but because they realised the implications of loose talk…

The real story of Nagadeepa restoration didn’t come out until many years later. Such a covert operation is inconceivable today with modern communications technologies!

After retiring from the public service in 1965, Premaratne devoted all his time to artistic pursuits. He copied key temple paintings and Sigiriya frescoes. He also developed a method of making authentic fibreglass replicas of moonstones, Buddha statues and other historical artefacts.

Using this method, he made over 20 replicas of prominent statues of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa for an exhibition on ‘Ceylon Through the Ages’ the National Geographic Society organised in Washington DC in 1969-70.

Using this method, he made over 20 replicas of prominent statues of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa for an exhibition on ‘Ceylon Through the Ages’ the National Geographic Society organised in Washington DC in 1969-70.

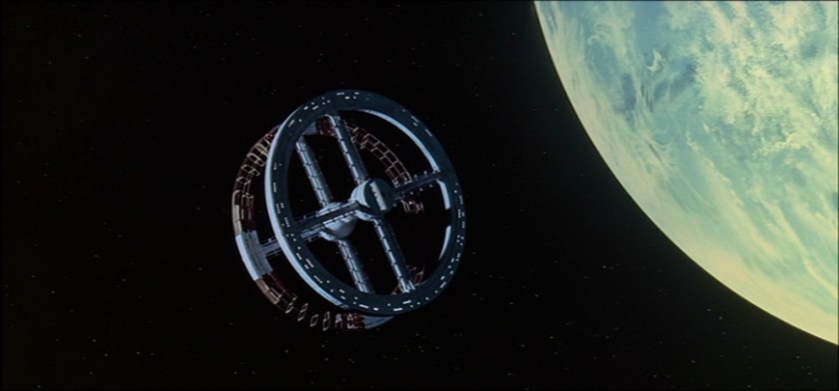

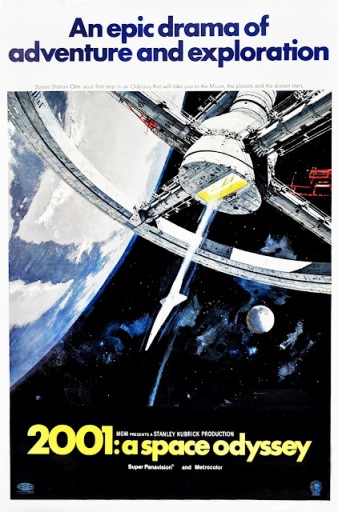

Recommended by his friend Arthur C Clarke, he spent a few months at MGM studios in Borehamwood, London, during 1966-67 where Clarke and Stanley Kubrick were filming their movie 2001: A Space Odyssey.

“Prema’s expertise in art and engineering was very valuable in the production of the movie’s special effects, and he assisted in building the spectacular space station,” Clarke said. (See: The artist who built a space station for 2001)

Premaratne was an erudite, soft-spoken man who remained creative into his 80s. I am privileged to have known him in his last few years. Some of his paintings are on permanent display at the National Art Gallery in Colombo and at the British Museum in London.