Remember the ‘Alphabet Soup’ made up of the endless acronyms and abbreviations (A&As) coined by the development and technology communities? (See July 2007 blog post: Who makes the best Alphabet Soup of all?)

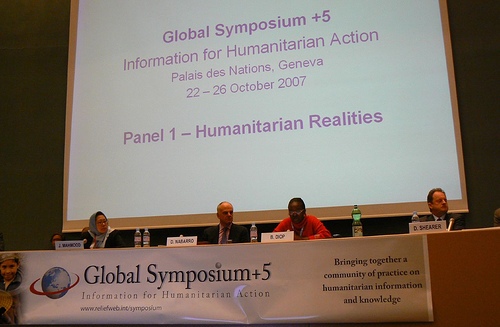

Last week in Geneva, attending UN OCHA’s conference on information for humanitarian action, I realised that the humanitarian community has its own share of A&As, some more memorable than others. HIC, SPHERE and FAST stuck in mind.

In this strange jungle, nothing is quite what they seem. While still recovering from that overdose, I was hit by the latest in the field of ICT (that’s information and communication technologies for you): believe it or not, it’s called MOO.

Well, actually the correct spelling is MoO (the middle o is lower case). It’s described as “a place where people SEEK and OFFER expertise, experience, project support, ideas, solutions and other resources that leverage on knowledge and ICT to fulfil the needs of ‘Emerging People, Emerging Markets and Emerging Technologies’.”

Wow, that’s somehow sounds important. This is going to happen as part of a big platform of events called Global Knowledge 3, inevitably abbreviated as GK3, to be held in Kuala Lumpur (KL), Malaysia, from 11 to 13 December 2007.

According to the load of hype on the conference website, the will be a ‘Virtual MoO’ and the ‘Physical MoO’ and the anticipated 2,000 conference participants will be browsing both, “seeking an exchange”.

Ok, let me not prolong the suspense any longer. MoO stands for Marketplace of Opportunities, which GK3 is supposed to create or inspire for all those engaged in using ICT tools for meeting the real world’s needs — to reduce poverty, increase incomes, create safer communities, create sustainable societies and support youth enterprise, etc.

Of course, if we browse through the massive GK3 website, we will be overwhelmed with a whole heap of technicalities, self-important hype and knowledge made incomprehensible to all but those who are already within the charmed ICT circle.

For example, take a deep breath and read how the conference is introduced:

“GK3 will explore concrete solutions and possibilities within the interplay, interface and interweaving of issues related to the Knowledge for Development (K4D) and Information and Communication Technologies for Development (ICT4D) in the context of our globally evolving societies, economies and technologies worldwide.”

Aaaaaaaaaaaaah! Or, shall I just say: Mooooooooooooooooo!

PS: Despite this skepticism, I’m planning to be there – I can’t afford to miss this chance to meet fellow activists who are so concerned about welfare at the grassroots.

PPS: An informed little bird says GK3 has milked development donors well and truly for this 3-day extravaganza. I hope someone will calculate the cost of development aid dollars per ‘Mooo’…